Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

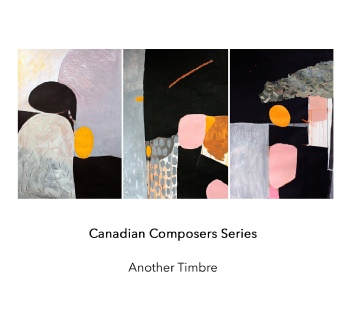

Canadian Composers Series

The Canadian Composers Series consisted of 10 portrait CDs presenting music by a number of Canada’s leading experimental composers. The first batch of 5 discs was released in February 2017 and the second batch was released in August 2018. The book accompanying the series contains an introductory essay by Nick Storring and extended interviews with all the composers involved.

Linda Catlin Smith Martin Arnold Isaiah Ceccarelli Chiyoko Szlavnics

Marc Sabat Alex Jang Cassandra Miller Lance Austin Olsen

Below you can read the preface to the Canadian Composers Series book by Simon Reynell, the producer of the series, and reviews of the first batch of five CDs which launched the series. The series booklet also contains reproductions of several paintings by Lance Austin Olsen and photographs by Nick Storring. You can read the full version of Nick Storring’s essay here

And there’s an excellent profile of the Series by Julian Cowley from Musicworks magazine, which you can read here

The 120-page book is free to anyone who buys 2 or more of the Canadian Composers Series CDs.

We have now sold out of copies of some of the original CDs in the series, but will send you downloads of these, as well as other CDs by the relevant composers:

Martin Arnold, Isaiah Ceccarelli and Lance Austin Olsen.

Special offer: buy all the Canadian Composers Series albums for £70 (10 CDs + downloads of ‘The Spit Veleta’ , ‘Dark Heart’, and ‘Bow’) - details here

Cover painting: ‘Transfiguration Triptych’ by Lance Austin Olsen

Canadian Series Reviews

There have been several excellent reviews of the Canadian Composers series discs. Here are some of them:

“In 2015, Simon Reynell, Another Timbre's proprietor, realised he was talking independently to three Canadian composers about producing discs of their music; as a result, the idea of producing a Canadian series emerged. In mid-2016, as part of its "Violin + 1" series, the label released Dirt Road by one of the three, the New York-born, Toronto-resident Linda Catlin Smith. Now, in the wake of the very positive reception afforded to Dirt Road, the Canadian series begins, with the release of five albums by five different composers, a further five albums being promised. Altogether, those ten releases should feature eight separate composers, with Linda Catlin Smith and Cassandra Miller each being responsible for two of the ten. While they are issued separately, not as a boxed set, the series is accompanied by an informative and stimulating booklet that includes interviews with all eight composers.

That group of eight composers calls to mind the Group of Seven (aka the Algonquin School), Canadian landscape painters who influenced the development of Canadian art. Although two of these eight were not born in Canada, three of them no longer reside there, and the eight are stylistically different, in time they seem destined to be very influential. The release of this Canadian series will undoubtedly come to be viewed as a landmark event.

Fittingly, the series opens with one of its aces, a double album of Linda Catlin Smith compositions. Where Dirt Road featured the fifteen-part title piece, from 2006, played by Apartment House members Mira Benjamin on violin and Simon Limbrick on percussion, Drifter presents more of an overview of her work, consisting of ten compositions from 1995 through to 2015. Recorded between February and July 2016, mainly at the University of Huddersfield, the pieces are variously played by Bozzini Quartet and members of Apartment House; as is typical of Another Timbre, the recording and sound quality is first-rate throughout, allowing the pieces to be heard to best effect.

The music here has all of the qualities that Dirt Road led one to expect of a Smith composition—gentleness, subtlety, emotion, attention to detail, a sense of melody, tranquillity—but goes beyond the range of that album. The quartet pieces (exemplified by "Folkestone" in the YouTube excerpt below) certainly display Smith's talents to excellent effect, but the fewer instruments that are present the better Smith tends to sound, as she seems to savour the sound of each individual instrument. That proposition is tested to the limit on three tracks that feature just one instrument, "Ricercar" played by Anton Luksozevieze on cello, "Galanthus with Benjamin on violin, and "Poire" with Philip Thomas on piano; all three draw one in and make riveting listening.

Drifter is impossible to fault; it is impeccable from first note to last.

While Linda Catlin Smith is not an unknown quantity, the other four composers featured in this set of releases are, which makes this an exciting voyage of discovery...

Toronto-based Canadian Martin Arnold was trained in the classical tradition at the University of Alberta but his live appearances are mainly restricted to monthly gigs playing electric guitar in a quartet that performs standards from the great American songbook. He comments that all the music he makes is in some way melodic, and that is fully borne out by his three compositions featured on this disc.

Interestingly, all three pieces bear titles that make reference to traditional dances in triple time—"Points and Waltzes," "Slip Minuet" and "The Spit Veleta"—making them a coherent set. That coherence is reinforced by the playing of Philip Thomas and Mira Benjamin; the first piece is for solo piano, the second for solo cello and the third a duet, fitting as the veleta (aka valeta) is a dance in which partners do different sets of co-ordinated movements.

However, once the music begins it is immediately obvious it is not dance music; although it maintains a steady rhythm, it does not compel movement in the listener, being more of a cerebral pleasure than a physical one. (Check the excerpt from "The Slip Minuet" below for example.) In the accompanying booklet, Arnold is quoted as saying he also thinks of his music as being slack, meandering, psychedelic and, even at its most ponderously enervated, dance music." In this, his judgment is as spot-on as his music...

By this point in the series, it is clear that these Canadian composers could not be identified as such by some common trait that gives away their nationality; each of them is an individual, uniquely different to the others. One of Isaiah Ceccarelli's distinguishing features is that he is the only one of the five who is credited as a performer as well as a composer, playing percussion on three of this album's seven tracks and percussion plus reed organ on another.

The redoubtable violinist Mira Benjamin plays on five tracks, all recorded in the UK—in London or Huddersfield—with the remaining two having been recorded in Québec, both duets between Ceccarelli and Katelyn Clarke on organetto, performing contrasting realisations of "Sainte-Ursule," a 2014 Ceccarelli composition. Ceccarelli and Benjamin perform as a duo on two tracks, parts one and two of "Oslo Harmonies," another 2014 Ceccarelli piece.

Those four tracks on which the composer appears alternate with three 2015 pieces for a string quartet or trio. Those with Ciccarelli are more improvised; tellingly, he says of them, "With Mira, I feel that it's more comfortable to have even just two notes written on a page than to be freely improvising—even if those two notes have got to last an hour, she'll make them sound great. With Katelyn on the Sainte-Ursule pieces we talked about it and found sounds that we liked and then did many takes of the same thing..."

The alternation is ingenious as it successfully blurs the distinction between improvised and notated music, and so highlights the composer's skill with harmony. Although Ceccerelli is the youngest composer on this batch of five, and the second youngest of the group of eight, Bow demonstrates he is one to listen out for in future.

Toronto-born, Berlin resident Chiyoko Szlavnics is the second female composer of this batch, although the ten albums of the whole series will be half female, half male. The three compositions here, dating from 2006, 2008 and 2015, provide snapshots of Szlavnics's composing career that throw light on her distinctive style. The album's eighteen-minute title track, from 2015, was recorded at Tonlabor in Hamburg and features the four-saxophone Konus Quartett, fitting as Szlavnics herself has history as a saxophonist. Alongside the saxophones, the piece includes sine-waves, as do many of her compositions. With long sustained notes from the saxophones and glissandi from the sine waves, part of the fascination of the composition lies in the shifting interactions between its component parts. Altogether, the effect is very different to anything else in the series and is simply mesmerising.

The other two tracks are different to that saxophone piece but also remarkably similar. They were again recorded at the University of Huddersfield and, each features members of Apartment House, a trio on the eleven-minute "Freehand Poitras" from 2008 and an octet on the twenty-six-minute "Reservoir" from 2006 (which means that Mira Benjamin appears again here, increasing her tally to four albums out of the five....) Again, long notes and sinewaves combine, creating moods that are just as beguiling as before, with the closing octet being a particular highlight...

To close this batch of five, the appropriately titled Harmony features three compositions by another Berlin resident, Marc Sabat, whose path has crossed that of Szlavnics several times. She has commented of him, "Since we both came to Germany I'm sure we've influenced each other to some degree, both personally and compositionally—Marc has definitely influenced me." Having studied violin, composition, and mathematics at university, it is no surprise that Sabat became fascinated by Just Intonation and uses it in his compositions.

On Harmony, two extended multi-part pieces performed by the Jack Quartet, "Euler Lattice Spirals Scenery" from 2011 and "Jean-Phillippe Rameau" from 2012, are separated by the shorter violin and cello "Claudius Ptolemy" from 2008. The extended prelude to the first piece features sustained notes as favoured by Szlavics, but beyond that Sabat is into more conventional string quartet territory. His use of Just Intonation seems to stem mostly from his fascination with sonority and harmony. All of his music here is characterised by its easy flow and the irrefutable logic of his progressions which carry the listener along with them, without any jolts or awkward moments.

It is obviously far too early to judge this Canadian Composers Series, with half of its albums still to be released and three of its eight composers yet to be heard, but its first five releases can be unreservedly recommended and leave one craving the next five.”

John Eyles, All About Jazz

“Tradition is a wonderful reality, but not understanding that the inner dynamic of tradition is to always innovate is a prison. This is eminently true in the case of music produced by the Canadian artists on the imprint Another Timbre. Beginning with Linda Catlin Smith, every one of the group under review has chiselled uniquely beautiful, but defiantly provocative works from out of the bedrock of contemporaneity. And although familiar forms such as the Piano Quintet (from Linda Catlin Smith) pop up in these performances, the music flies in the face of all conventions.

Indeed, these artists force listeners to reconsider what tradition is. For example, Marc Sabat, on Euler Lattice Spirals Scenery, positions himself in creative conflict with age-old protocols about how a string quartet ought to work. Likewise with Chiyoko Szlavnics, whose Reservoir sends strings rippling against flute, accordion and percussion. It becomes clear, then, that having actively thrown overboard melodic, structural and harmonic hooks that have been expressively blunted through misuse, these artists seem to build from what might– or mightn’t-be left.

Just as Frank Zappa once famously asked, “Does humour belong in music?” one feels compelled to also pose the question: “Does mathematics belong with art?” The answer in the architectural geometry of Smith’s Drifter is a most emphatic “Yes.” Its resident geometry, however, seems to have been informed by French curves rather than by set squares. As a result her spacy Piano Quintet seems to defy definitions of beauty, which although essential to Smith’s credo, is bereft of perfumed listener-ingratiating beauty and resplendent in the natural sounds of tuned percussion, bowed strings and plucked guitars.

The emerging members of Apartment House and the Bozzini Quartet float effortlessly over Gondola and Far from Shore seemingly tracing their fingers delicately over the contours and hachures of the map of a priceless treasure without compromising the location of its secret world. In all of this and other music on the double disc Smith makes use of time and space as well as championing the cause of her singularly poetic approach to the all-important beauty of the melodic line.

Meanwhile Martin Arnold’s music for Points and Waltzes, Slip Minuet and the title work of his album The Spit Veleta comes alive in the silvery tonal purity and exquisite subtlety of phrasing by its interpreters who bring fresh ears to these radiant gems. Similarly, Isaiah Ceccarelli’s seven pieces on Bow are designed to extract the maximum tonal depth from strings, reed organ, organetto and percussion; as does Chiyoko Szlavnics from strings and reeds and woodwinds, and the Jack Quartet with violin, viola and cello on the exquisite narratives on Marc Sabat’s Harmony.

It all bodes rather well for the future of this Canadian Composers Series and for Sheffield, UK-based Another Timbre, a label whose presence in contemporary music is doing yeoman work to shine a brighter spotlight on new music that is being beamed by across the world.”

Raul da Gama, The Whole Note

Preface to the Canadian Composers Series book

This series is emphatically not intended to be an exhaustive documentation of contemporary music in Canada. It neither attempts to offer an encyclopaedic overview, nor claims to present ‘the best of’ Canadian experimental music (however that might be judged). It comes rather from a moment a couple of years ago when I realised that I was talking independently to three Canadian composers about producing portrait discs of their music. It struck me that it could be interesting to present their music together, although they are stylistically very different and there’s nothing in their music that could be identified as a common national trait. In fact all three composers are defiantly individual voices, not belonging to any school or tendency, and perhaps that is partly what interests me about their music.

Having realised this coincidence, I started to think of other Canadian composers whose work I knew, and to explore the music of others who I didn’t yet know. And so the idea of producing a Canadian series emerged, covering at first three, then five, then finally ten CDs as I became more and more taken with and drawn to the richly diverse works being produced by musicians in or originally from a country that is so often eclipsed by its more powerful, populous and louder neighbour.

I have never been to Canada, so my research was done from afar. However there are significant connections between Yorkshire (where I live) and several Canadian musicians and composers. Both the Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival and the music department at Huddersfield University have frequently hosted the Quatuor Bozzini, who constitute one of the key hubs for contemporary music in Canada, and, reciprocally, musicians from the university have toured Canada, creating more bridges. As a result, several Canadian musicians have gone on to study in Huddersfield, including two of the composers featured in the series, and the violinist Mira Benjamin, herself a former member of the Bozzinis, who performs on most of the CDs in the series and is an extremely effective ambassador for Canadian experimentalism abroad.

The selection of composers featured in the series is inevitably subjective, and has arisen as much through happenstance flowing from these Yorkshire-Canada links as through any supposedly objective assessment of the merits or significance of their music as compared to that of others. In preparing the series I have discovered several other Canadian composers whose work I enjoy, and if I had enough time and money, I could happily produce another ten CDs covering music by composers such as André Cormier, Daryl Jamieson, Michael Oesterle, Barbara Monk Feldman, Daniel Brandes, Allison Cameron, Rudolf Komorous, Anna Höstman, Mathieu Ruhlmann, Christopher Reiche, Nick Storring, eldritch Priest, Jason Doell, Mark Hannesson… the list could go on. I seem to have stumbled on a corner of the contemporary music world that is both particularly rich and somewhat under-exposed.

Simon Reynell, January 2017

Lance Austin Olsen ‘Momentary Glimpses’

Photo: Nick Storring

Photo: Nick Storring

Lance Austin Olsen ‘Blue Drift Hotel Londres’

More reviews

“Among the most interesting releases to have come out in the opening months of this year are the first five discs in Another Timbre‘s Canadian Composers Series. It’s an ambitious project that seeks to provide an overview of, if not the entirety of contemporary Canadian compositional thought (which is hugely diverse), then at least some of its more contemplative protagonists. The five composers featured on these discs – Martin Arnold, Isaiah Ceccarelli, Marc Sabat, Linda Catlin Smith and Chiyoko Szlavnics – in some respects have a great deal in common, though it would be pushing it to think of them as musically ‘related’. If anything can be said to typify them all, in addition to the contemplative aspect i mentioned, it’s a certain type of intensity that, whether preoccupied with carefully-managed processes or a more free-form arrangement of materials, seems utterly focused to the exclusion of all else. These are composers who gaze fixedly at their ideas in a way that makes a very deep impression and in its own way leads to a distinct kind of quiet provocation.

For Martin Arnold, that provocation arises out of what he describes in his music as its “formlessness”. Making sense – formal, harmonic, melodic, rhythmic, aesthetic – of the three works on his disc is an engaging challenge. i love Arnold’s summary of his work as “slack, meandering, psychedelic and, even at its most ponderously enervated, dance music.” There’s a great deal of truth in those words. Philip Thomas’ rendition of Arnold’s 2012 piano piece Points & Waltzes both grapples and playfully toys with the work’s never-ending melodic impulse. Based around the middle of the instrument, an upper voice provides something that one could just about call a countermelody, its notes sometimes so isolated that their connectivity is questioned. Slip Minuet for solo violin (played by Mira Benjamin) is similarly melody-obsessed, here resembling a seriously slowed-down dance, retaining something of the energy of the ‘full speed’ version but also sounding slightly unreal due to the rhythmic incontinuity brought about by its tempo, which also heightens a sense of repetition in certain harmonic progressions and rhythmic cells. Both pieces exhibit a curiously uncanny quality emanating from their unstoppability, something that finds a kind of synthesis in the duet title work, piano and violin now collaborating in music that displays an insatiable melodic instinct while again challenging its horizontal integrity. All three pieces experience a mid-point tilt on their axis. Points & Waltzes abruptly finds itself in a weirdly engrossing place of low register vagueness, every now and then clarified with triadic focus, bringing both Messiaen and Finnissy to mind; Slip Minuet splinters into pizzicati, losing its rhythmic sense almost entirely, sounding heavily filtered to the point that the music even feels rather alien. The Spit Veleta turns the tables on the other two works, challenging points of continuity by greatly stretching them with long suspended notes/chords. i have to say i found the push and pull of this connective plausibility in all three pieces to be very stimulating, and in the case of this last piece, the inscrutable beauty of its latter half is a genuine wonder to behold.

The ten works contained on the double-album devoted to Linda Catlin Smith‘s music – performed by Apartment House and the Bozzini Quartet – display a similarly beautiful, usually folk-infused, countenance. That being said, some of them are tougher nuts to crack. Both the 2013 Cantilena for viola and vibraphone and 2010’s Far From Shore for piano trio pose similar questions of connectivity to Arnold. The relationship between the parts in these pieces is often hard to define, gently massaged between tenuousness and credibility; again, there’s engagement to be found in this tension, though Smith’s soundworld is sometimes sufficiently aloof (though a better word might be introspective) that it can feel a touch alienating. Galanthus for solo violin is similar in this respect, not unattractive but hard to penetrate, whereas her 1999 string quartet Folkestone, while passing through periods of detachment also alights on some lovely episodes of waxing and waning counterpoint, its fragility countered by the unity displayed by the quartet as a whole. More potent by far is Smith’s short solo piano piece Poire, all the more striking for its entire focus on assertive monody, notes occasionally (gently) reinforced with octave doublings. A charming piece, that’s only bettered by the astonishing, insistent atmosphere of Moi Qui Tremblais, where low moody piano chords are softly pummelled and splashed by a bass drum and cymbal in conjunction with drawn-out streaks of violin pitch. It’s impossible not to be pulled deeply into its immersive, all-enveloping soundworld.

Harmony, the disc focusing on music by Marc Sabat – performed by the Jack Quartet – is well-named. His work emerges from the juxtaposition, superimposition and general mingling of pitches so as to both explore and question conventions of intervallic relationship, complicated by Sabat’s habitual use of just intonation. The five parts of Euler Lattice Spirals Scenery don’t so much develop as undergo a creeping evolution, encountering and becoming fixated on certain notes, though often these turn out to be new tonal centres that subsequently alter one’s perception of the music’s harmonic foundation. In the opening Preludio, these ‘tonics’ act akin to ‘shelves’ that the music can sit on for a while, while the two Pythagorus Drawings explore the effect of hocketed accents around similarly continually shifting tonalities. The pair of Harmoniums, one for Claude Vivier, the other for Ben Johnston, are more demonstrative. The former features a melody seemingly trying to break out from within shafts of tilting harmonic tangents, becoming a kind of ‘harmonic melody’, articulatory fragile but projected strongly, with confidence; even more paradoxical, it becomes rhythmically vigorous yet attaining ethereality, the music less ‘real’, somewhat ghostly, before culminating in a convoluted, multi-layered hymn. The latter Harmonium is melancholic, with something akin to John Dowland lurking beneath the surface; it brings to mind some of Thomas Adès’ (better) music, feeling distinctly ‘guided’ by a kind of unheard éminence grise determining the musical material. As time goes on, it feels very much as though the piece is wrangling with this pre-existing material, though Sabat keeps this sufficiently at a distance that it could all potentially be just an illusion. While the four sections of Jean-Philippe Rameau are harder going, the continuous harmonic movement having a more arbitrary nature, Sabat’s 2008 work for violin and cello, Claudius Ptolemy, is excellent, occupied with a simpler, quasi-diatonic palette that prefigures the Harmonium for Claude Vivier by being a cross between a melody and a chord progression; its alternations between clean intervals and buzzing dissonances create an engaging dialogue, and the possibly cyclic nature of the material keeps one guessing.

First impressions often turn out to be mistaken in the music of Isaiah Ceccarelli, represented by seven recent pieces (2014–15) on his disc. Saint-Ursule #11 for organetto and percussion displays another angle on apparent disconnectedness, the two parts initially seeming entirely individual, performing side by side but otherwise remote, but as it progresses one becomes convinced it’s actually a dialogue, and maybe even two facets of a single musical voice. Falsobordone, on the other hand, initially seems to have a drone-like harmonic sense, but this is revealed to be a slow-moving progression (albeit one that doesn’t really want to progress), inching itself along. Ceccarelli composes some of the most dense music heard on these five discs. Oslo Harmonies, divided into two parts, is filled with compacted sound, the first part (for violin, reed organ and percussion) a pause-less chord that moves through marvellous colours, at the same time flitting between harmonic clarity and obscurity, to hypnotic effect; it’s as though ‘clearer’ chords were trying to break through to the surface, another probably illusory effect. The second part (minus the organ) is filled with far more pale, wan material; yet another example of questionable connectivity, the two instruments gradually make contact apparent but while the musical elements become clearer their direction and the nature of the interaction seems more vague (another nice paradox). Every instance of boldness is qualified in this way, ultimately ending in a place of fragility, the weakness of its sounds inversely proportional to how arresting they are. Sainte-Ursule #2 is the standout work on this disc, a mid-register shimmering cluster from the organetto impinged upon by the percussion in the form of soft bowed and struck sounds, causing the cluster to alter. It’s an extremely dreamy piece, floating in its own little world, as though it were taking place within a snowglobe.

To my mind the most striking of these five remarkable discs is the one featuring three works by Chiyoko Szlavnics. i reviewed the title work, During a Lifetime, at its UK première at HCMF 2015, and Konus Quartett’s recording of the piece is just as dazzling. Szlavnics arranges the juddering, shimmering and rippling clusters such that each undergoes the same envelope: fading in, hovering for a time in a throbbing quasi-stasis, then fading out. It later becomes more complex, particularly around halfway through, leading to gorgeously rich agglomerations of close-proximity pitch, and later still pauses feel deliberate in a sense of preparing for what’s to follow. This nicely breaks up the organic, almost entirely electronic sound of the first half of the work, emphasising that there are, in fact, four saxophones present, despite aural appearances to the contrary. The conclusion, now sounding akin to bells, is simply amazing. Szlavnics’ 2008 work Freehand Poiras for two violins and cello at first sets up plaintive compound minor thirds, to which an extra note is added, with a propensity to sag and slide, causing triads that vary in their nature. Some are more static, with slight clustered shimmering, and there’s more emphasis here on near-unisons (around halfway through all three players are almost in octaves). It may prove a little too detached for some, but the piece ultimately inhabits a cool stillness, its harmonies as bleached as the snow white image on the album’s artwork. Composed in 2006, Reservoir for eight players and sine waves is a relatively early work, but easily one of her best. Small clusters become ‘fleshed out’ by the ensemble, turning into extremely complex chords, and with a highly unpredictable, intuitive sense of development. Along the way, it compresses into a high register cluster, expands into a choir of seemingly vast bowed wine glasses, comes to resemble a subdued squeezebox, culminating at its centre in a wondrous climax that sounds genuinely massive, as though it might be swirling around at immense speed. What follows is breathtaking, developing around central clusters, essentially the core of the music, establishing a real sense of perspective: surface elements moving and interacting on and/or above (even embedded within) this cluster-core. Whereupon an entirely unexpected pause ushers in a soft, small extended coda focusing on more clear collections of pitches nestling alongside each other. Ravishingly beautiful.

Another Timbre really has outdone itself with this outstandingly impressive collection of discs. Each album feels like a highly concentrated dose of its composer’s output, providing both a fabulous introduction and opportunity to dive deeply into their respective musical approaches, which, as i said, while technically unrelated have a great deal in common in terms of their aesthetic outlook. One awaits the next set of discs, coming out later in the year, with bated breath.

In the meantime, these discs are available directly from the Another Timbre website, for the paltry sum of just £40 for all five, which includes an invaluable 116-page book containing in-depth interviews with the composers (including the ones featured on the next five discs).”

Simon Cummings, 5:4

And more reviews

“In its own quiet way, the Another Timbre Canadian Composers Series concerts at Cafe Oto are one of the major events I’ve been looking forward to in 2017. Over the past year or so I haven’t been alone in noticing how much of the freshest, most intriguing and affecting music has been coming from Canadian composers. This week, there are three nights of music this week focusing on new music by these composers and more at Cafe Oto. The gigs are to launch the first five releases in a ten-disc Canadian Composers Series on Another Timbre. I’ve had all five on heavy rotation at home the last few days and will need to write more about them during/after hearing the live shows.

The double CD of works by Linda Catlin Smith, Drifter, opens with a duet for viola and vibraphone. Cantilena‘s instrumentation recalls the magnificent 70-minute violin and percussion Dirt Road Another Timbre put out last year and is a brighter, briefer work with fewer complications to mull over. Any suspicion that the album would offer diminishing returns are evaporated by the 2014 Piano Quintet and Drifter itself, another odd pairing of instruments, guitar and piano.

The Quintet presents a hothouse atmosphere of lyrical flourishes in the strings, framed by restive, unresolved harmonies in the piano. It’s like a passage from romantic European chamber music at its ripest, held in suspense, their details enhanced while their function is diminished. When the strings finally break into sustained drones against the piano, it serves only to maintain the cool tension already achieved. In Drifter, the two instruments play in turn, the guitar as an echo of the piano, the same chords but transformed by the change in timbre and decay, surprising the unsuspecting listener with the way the harmonic material appears to be subtly transformed. Eventually, each takes turns in leading on the other, or playing in unison, an unhurried interplay of two partners sounding out each others’ qualities.

Over ten pieces, Apartment House and Quatuor Bozzini present Smith as a composer capable of finding great diversity of expression within a single, coherent compositional voice that focuses on depth more than breadth. Suggestions and traces of other music styles are recalled, but never in pastiche. Those string arpeggios in the Piano Quintet relate equally to folk playing as to a salon. The clearly delineated phrases of the Ricercar for solo cello are modelled on Baroque music but do not imitate. Unexpected shifts in mood come in the strange processional Moi Qui Tremblais and in the final string quartet, Folkestone, a cycle of introspective fragments in fragile diminuendo.

A small book of interviews has been published together with the CDs. From what I’ve skimmed so far, some common themes emerge between composers: the isolation, allowing them to work in blissful ignorance of more common theoretical hang-ups occupying colleagues’ minds in the US or Europe, is spoken of approvingly more than once. There’s also a repeated referral to the legacy of John Cage, particularly via Morton Feldman. Previous generations who might have claimed such an influence would frequently be stridently avant-garde, often more in style than in substance. While never sounding derivative, distinct traits can be observed that show a firm understanding of Feldman’s music. Ambivalence of mood, the embrace of traditional harmony while simultaneously rejecting its traditional structural function. The allowance of stasis, a musical ‘surface’ of sustained dynamics, typically tending towards the quiet. A careful consideration of instruments’ attributes, enabling otherwise unusual combinations of instruments to be heard in new ways, in contrast or in complement.

Another echo of Feldman can be heard in Martin Arnold’s album, The Spit Veleta. The three works on this disc comprise a sort of extended suite. In each of them, the music continues in a slow and seemingly aimless way, yet always with a faint suggestion of a waltz. There’s always the sense of something a little faded, diffuse, of what might have once been a more rigid order. If the music that is left is more elusive, then it is at once more free yet more sophisticated. In Points & Waltzes for solo piano and then in Slip Minuet for solo violin, each with titles referring to dances in triple rhythm, the musician (Philip Thomas and Mira Benjamin, respectively) circles elegantly, if a little erratically. The two combine on the final, title work.

In each piece, a change occurs halfway through. The delicate counterpoint of Points & Waltzes gives way to a relentless tessitura of chords in the piano’s lower register. Slip Minuet suddenly turns to pizzicato, articulating a downbeat to a dance otherwise inaudible. There is more silence than sound, yet the underlying shape of the music is still clearly perceptible. It sounds like the violinist is accompanying a tune heard only in her head. In The Spit Veleta, the duo build a slow, complex rhythm of intertwining dances, before freezing, erasing almost all memory of the music with a succession of soft chords and dyads, played simultaneously. The piano sound decays, revealing the violin’s sustained tone underneath, a faint coloration of the silence suspended between one isolated chord and the next.

There’s a beautiful poignancy and melancholy in these pieces, found in the way that Arnold allows the matter of his music to be reduced to the most spare and etiolated state without ever suggesting that the music is withholding anything from the listener. For what could easily be considered as studies in decay, there is a welcome lack of postmodern didacticism. In fact, it reminded me more of modernist thinking. I’ve referred before to Guy Davenport’s quote that completing an image “involves a stupidity of perception“. Hugh Kenner observed that in the twentieth century, Westerners learned to interpret fragments outside of their original settings, gathering meaning from non-consecutive arrays. As Ezra Pound wrote, “Points define a periphery.” Perhaps in the respect these Canadians’ sensibility is like my own Australian one: as colonial cultures, we can accept ruins as what they are, not just what they once were.

This post is already too long and I want to write about Marc Sabat and Isaiah Ceccarelli after I’ve heard them live at Oto. Right now I need to mention Chiyoko Szlavnics’ remarkable During a Lifetime. Szlavnics pits live acoustic musicians against pure sine tones; a combination well-known for its use by Alvin Lucier, Warren Burt and others. While those latter composers typically exploit the small differences in intonation between acoustic pitches and pure tones, Szlavnics works with the same deceptively simple combinations to very different ends. During a Lifetime is for saxophone quartet and electronic tones, but for much of the piece sounds like neither. A large, complex multiphonic sound swells, pulses, grows rough and then smooth again as variances in tone between the instruments modulate each other as much as the sine waves do. The electronics merge and disappear, then emerge again as one of the voices in the ensemble. This played by the Konus Ensemble, who do an exceptional job of balancing clear tones against some subtle, raspier edges. I heard these guys’ superb performance of Jürg Frey’s Memoire, Horizon at Huddersfield a couple of years ago, and they’re playing both pieces at Cafe Oto on Thursday.”

Ben Harper (1), Boring Like a Drill

“Three nights last week at Cafe Oto to hear concerts dedicated to The Canadian Composers Series on Another Timbre. As always, you get new perspectives on hearing and seeing music performed live, compared to what’s on the record. In their performance of Linda Catlin Smith’s Dirt Road, Mira Benjamin and Simon Limbrick revealed just how sparing, yet quietly decisive each gesture must be. The music’s language is pared back to the bones, yet never consciously feels empty or repetitive.

It was strange how different Chiyoko Szlavnics’ During a Lifetime sounded on the night. I’ve already noted how Szlavnics’ use of sine tones mixed with live instruments differs from their usual exploitation of psychoacoustic phenomena. This distinction became clearer in concert: the electronic tones act as an instrumental voice in their own right. At times, the musicians stop playing altogether, revealing harmonies – even chords – in pure tones before the instruments come in again to compound the sound. The music took on a poignant, melancholy aspect. The Konus Quartett reproduced their clear, pure tones beautifully.

The series ended with a world premiere, Lutra for solo cello, by Martin Arnold. I’ve drawn comparisons with Morton Feldman’s music before so I’ll add another here: the elevation of instrumental timbre as a compositional element, coupled with the determined restriction of that instrument’s sound. As with much of Feldman’s solo cello writing, Lutra remains constricted to harmonics and the highest registers throughout, without any of the instrument’s famous sonorous qualities. A long aria for countertenor, unaccompanied save by the cellist Anton Lukoszevieze humming (intentionally) for several passages. Taking sound at its most frail and revealing how it can endure.

The series began with a set of what were apparently largely improvised duets by Isaiah Ceccarelli and Katelyn Clark. Clark played organetto while Ceccarelli played percussion, a small keyboard or, unexpectedly, sang. Two such duets open and close his album Bow, while the rest of the disc contains compositions for string quartet and trio and two more semi-improvised duets, for violin and percussion. All of them share a strangely rustic aspect, with gently rocking, slightly ragged harmonies that, on occasion, give way to brief lyrical exclamations of utmost restraint. The subdued and homespun atmosphere kept reminding me of the British avant-garde in the early 1970s and, in a similar way, these deceptively simple pieces are staring to grow on me.

As a fan of James Tenney and Ben Johnston I was eager to hear more of Marc Sabat’s music. The two string quartets on Sabat’s CD, simply titled Harmony, share a soundworld closer to Tenney’s music for string ensembles, while combining both composers’ interest in making music for tuning systems outside of conventional Western equal temperament. The JACK Quartet gives nicely studied readings of 2012’s Jean-Philippe Rameau, in which Sabat uses just intonation to add a subtle torsion to an unbroken chain of chords, and the earlier, austere duet for violin and cello Claudius Ptolemy. In the latter work, sustained, isolated sounds brush up against each other like a piece by Webern in slow motion.

The other quartet, Euler Lattice Spirals Scenery, is a longer and more varied work with occasional passages of more hurried activity. The tuning is based upon applying Euler‘s concept of the Tonnetz to pure harmonic intervals, without the need to restrict them to a palette of 12 fixed tones. The phrasing and some of the harmonies used are often reminiscent of Cage’s String Quartet in Four Parts, with added piquancy from the microtonal shifts in intonation. At Oto, members of Apartment House played a 2015 work, Gioseffo Zarlino, where Philip Thomas joined in on piano to make an oddly charming combination of tempered and untempered sounds. The night before, Thomas’ solo set included two more of Sabat’s works. Without having to wonder about tuning theory, Nocturne and Ich fahre nach Köln allowed me to admire the way Sabat could get lopsided figures to loop and intertwine without sounding congested, like an irreverent Scelsi, relieved of a spiritual burden.”

Ben Harper (2), Boring Like a Drill

Photo: Nick Storring

Photo: Nick Storring

Photo: Nick Storring

Lance Austin Olsen, ‘Blood and Memory’

Photo: Nick Storring

Photo: Nick Storring

Linda Catlin Smith Martin Arnold Isaiah Ceccarelli Chiyoko Szlavnics Marc Sabat Cassandra Miller Alex Jang Lance Austin Olsen Cassandra Miller Linda Catlin Smith

Drifter The Spit Veleta Bow During a Harmony O Zomer! momentary Dark Heart Just So Wanderer Lifetime encounters