Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

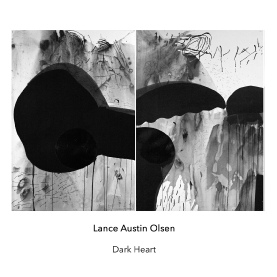

at128 Lance Austin Olsen - ‘Dark Heart’

1 - Theseus’ Breath (realisation #1) 9:54

Apartment House

2 - Dark Heart (2013-2016) 32:01

Lance Austin Olsen & Terje Paulsen

3 - Theseus’ Breath (realisation #2) 9:48

Ryoko Akama, Patrick Farmer, Isaiah Ceccarelli, Katelyn Clark

4 - A Meditation on the History of Painting (2017) 27:57 youtube extract

Gil Sanson & Lance Austin Olsen

Interview with Lance Austin Olsen

Extracts from an extended interview with Lance Austin Olsen in the booklet which accompanies the Canadian Composers Series CDs

Which came first, the art or the music? And do the two things feel closely linked or like separate practices?

The visual art came first. I was accepted at Camberwell School of Art in London in 1959 when I was just sixteen. I’d always been a shy kid that liked drawing and painting and hated actual school, so it was great being put into an environment where the teachers were, amongst others, Frank Auerbach, RB Kitaj, Patrick Proctor, Henry Inlander, Michael Rothenstein and above all Euan Uglow, whom I credit for teaching me how to look and draw with his meticulous and sometimes irritating methodology. This was the best that could ever have happened to a sixteen-year-old misfit.

When I got married and moved to Western Canada and had a first child, there was no money for extravagances like record players and buying records, so I didn’t hear any of the artists from the 70’s and most of the 80’s, and to this day I don’t know who most of them are or what they sound like. I spent my time listening to the environment that we lived in. I don’t own an iPod and I never walk around with earphones listening to music at the expense of the wonders of my actual environment.

We lived on a small island in the woods for a number of years so I became very fond of the quiet punctuated by the occasional chain saw. I only got involved in audio work and experimentation in about 1997-8, and I view it as painting and drawing with sounds. It is now intertwined with my visual arts practice to the extent that I now couldn’t imagine one without the other.

The way you describe listening to your environment rather than records is reminiscent of Cage’s writing, but I don’t suppose you were reading him either? Were you listening to music of any sort before you started experimenting with sound in the late 90’s?

When I was at Camberwell Art School in the late 50’s early 60’s the dances were strictly traditional jazz and I really liked, and still do, George Lewis and Bunk Johnson and collected a fairly substantial amount of albums by King Oliver and Louis Armstrong and all the early bluesmen such as Blind Blake, Lemon Jefferson, Ma Rainey and my favourite of all time Blind Willie Johnsons Dark Was The Night, Cold Was The Ground. I still have all these albums and all the John Coltrane and Monk and Johnny Hartman albums that I loved. I also loved Verklärte Nacht, op 4 for String Sextet by Arnold Schönberg; it was dark and interesting and my visual work had also become dark.

Suddenly it seemed R&B took over the whole art school circuit and we went to Eel Pie Island to find that traditional jazz was basically a thing of the past; ironic, since it was always a thing of the past. Like all my contemporaries we went to the Marquee and the Station Hotel to see the Stones and later when the Crawdaddy club moved, the Richmond Athletic club to see the Yardbirds and all of Georgio Gomelski’s collection of bands. The Beatles hit the scene at the same time. Their music was both danceable and seemed different. At the same time during this whole period I had become more and more interested in classical music, particularly Schönberg and late Stravinsky, and modern jazz, as well as my ongoing love for the old blues singers.

I left for Canada around the time that Sgt Pepper Lonely Hearts Club Band was released and I still have only a mono LP of the work. The music I listened to in Canada was pretty much what was on the radio. Whatever was on was what I listened to. When I was driving around I would often put the radio on auto scan and it would play 10 seconds of every station it could find. It drove my wife crazy. I wasn’t reading John Cage, I was reading Gurdjieff and Ouspensky and later Suzuki Roshi and trying to raise children and earn a living without abandoning painting.

In the mid 80’s I bought a record player and began to play all my great albums again. I also became fascinated by the work of Friedrich Jurgenson. So Trad Jazz, blues, R&B, Modern Jazz, a Radio on auto scan, chainsaws in the quiet of the woods, Schönberg and Friedrich Jurgenson, the recipe for an audio feral child.

Then in the mid 90’s a young man called Jamie Drouin showed me a piezo microphone. I taped it to a copper plate that I was working on, and there it started. I’ve collaborated with Jamie on and off since then, and more recently with a number of other musicians.

How did you meet Jamie?

By 1984 I was totally pissed off with the whole art scene, self-serving curators, whining artists; the whole thing. I looked around to see what else I could do, and it struck me that instead of putting pictures on the walls of empty buildings and hoping to sell them, I would somehow build a small luxury hotel with pictures on the walls to look at and sell the beds nightly. I won’t get into how I did this with just credit cards and bullshit, but I managed to open a small luxury fine arts hotel downtown in July of 1986. There were no hotels like this in Victoria at that time, and I ran it with my wife for nine years.

We had to prepare breakfast for all of the rooms, which entailed us getting up at 4am seven days a week and working in the kitchen. We never spoke, it was quiet, just the sounds of the building waking up. It was wonderful. But in 1995 after an extended legal battle with a partner that I had brought to expand the business, my wife and I walked out with nothing. I had no money and I needed a job, and the local art gallery needed a part time assistant for its art rental department. They hired me, and here I was working in a place full of people who pissed me off. A part-time, evening security guard started to talk to me, and a few weeks later I saw his photographs. They were fantastic. That is how I met Jamie.

We started working together on various projects and made a couple of videos, including one as an installation called Next Stop. I had submitted it to a guest curator at the gallery under a false name and they loved the piece. When they found out it was the work of Jamie and I it was too late to backtrack, but a new policy forbidding staff to submit work for exhibition was put in place.

Jamie left the gallery to work as a website designer for a year and during this time he approached me with the notion of doing a series of audio performances in a local commercial gallery. Given that it has always been my belief that I could do pretty much anything I set my mind to, and given my belief in Jamie’s abilities, I said, what the fuck, the worst that can happen is that it will all be shit. So that’s what we did. This was the first venue for experimental audio in Victoria; nobody was interested at that time, so we had to do it and we put on a series of concerts called Sounds in a Room.

Tell me about Dark Heart, the longest piece on your CD. How did that come about?

I’d had this dark idea in mind for a time, and my paintings were getting darker and darker again, partly because I had a lot of black paint. People think you’re painting about death and doom, but sometimes it’s just because you’ve run out of colours for a while and the black and whites are looking pretty good. I was really pleased with my paintings at this time, and then the Norwegian musician Terje Paulsen sent me a recording with an idea that we might collaborate on something. It was a long field recording with bits with a guitar doing a kind of metallic clunking. As Jamie Drouin said, it sounded like a 15 minute thing that had been stretched out to an hour. So I tried doing something with it, but I was having trouble, and I was at a point where I didn’t want to mess around too much with someone else’s work, cutting large chunks out or playing parts backwards or whatever. So I left it aside on my computer, but then after a couple of years my computer filled up, and I had to choose to get rid of some stuff. So I re-found Terje’s piece and had a listen, and thought ‘oh yes, that’. But then I thought, ‘do you know, I want to really chop this thing up’. I couldn’t remember which bits I’d done, and what was still Terje’s. So I just set to and cut around a lot and changed the tones on it. I’d been working on a project that involved old radio plays, and I thought that might work here and help hold this thing together. So I really hacked it about, and I thought he’d be upset that I was taking so many liberties. Meanwhile Terje had pretty much disappeared. I heard that he’d been unwell, so I thought I’d better try to find him and see what he thought; I wasn’t going to do anything with the finished piece without his agreement. So I managed to contact him and it turned out he’d been in hospital for a year, and I sent it to him, and he sent back this long letter saying how wonderful it was and that he absolutely loved it.

So what were you actually doing on it? You were chopping up his stuff, but also adding things of your own. How were you making those sounds?

I forget exactly. I had some field recordings from when I’d walked through the local history museum with my recorder and there was an organ going and animal noises and so on. And I have a couple of guitars which I never tune (I don’t play tunes!) but I record sets of tones on them using e-bows which I put on the computer. And there’s this big earthenware jug that gives some great sounds if you get the microphone right inside. And once I’ve gathered all this stuff together and organised it into a set of harmonic tones, again it’s just like painting, you just step back and decide what might go where, what fits with what and how to re-organise the different elements. I enjoy the process, but the way I work means that when I finally finish a piece I usually don’t have a clue about exactly what I did to get there.

Now that you’re doing a lot more with sound, do you ever start a painting with the intention that it should become a graphic score, or is the process always more complex than that?

No I’d never start off with that clear intention. But it’s interesting that working more with sound has affected the way I paint. I do movements and brush strokes that are a bit rhythmic or musical, and it’s like there are concepts of sounds running through my head when I’m painting. So there are connections but they only come out in practice in the work when I see or hear something that sparks off a whole load of ideas for developing things. In my studio there are two definite sides: the painting stuff on one side with the paper and lots of old brushes and dirty water left in old yoghurt pots, and the other side has all the audio stuff I use, like stones and rocks and scraps of metal, but also lots of bits of electronics. Jamie says that the two sides are really the same except that the music side can’t have the water.

Moving back a while, why did you first come to Canada?

Back in 1967 I met a woman from California through a friend, and we ended up together, and we still are together. I’d been in New York, but I didn’t like it there; it was crazy. I knew people there and perhaps if I’d stayed I’d be rich and famous now, but that’s just not for me. We decided to move as far away as possible from both families, and I knew a few people who’d moved here, so we did and we liked it.

Do you think that moving to Canada was partly a desire to get away from the pressure of being in a big cultural centre like London or New York?

Very much, yes. Even when I was still a kid and went to Camberwell Art School at 16, the person I really admired and looked up to was Alberto Giacometti. What I loved about him even more than his art was his attitude. He always felt that you should just do your work. The fact that he got picked up and became famous after a while didn’t affect him; he kept focused on his work and felt all that fame and fortune stuff was just for kids, just bullshit. You shouldn’t be distracted by an agent saying ‘we just got 2 million for that, so can you do five more of them?’ For me that’s no way to work; I just want to be left alone in a quiet place where I can think about things and get on with the work.

So have you managed to earn a living from your art, or have you always had to take day jobs?

I’ve always had day jobs. I sell a few paintings every now and again, and that’s great because you don’t have to worry about money for a while, but I’ve always had to work. When we first moved here I was a cigarette salesman, even though I didn’t smoke, then I worked as a salesman for a neon sign company, and I taught silkscreen printing for a while. If we ran out of money we’d drive down to California to stay with my wife’s family, but then something would always come in. At one time we moved to a smaller island where we built a house, and through that I learned carpentry. Everything around here is built of wood, so if you can build stuff there’s always some work you can find.

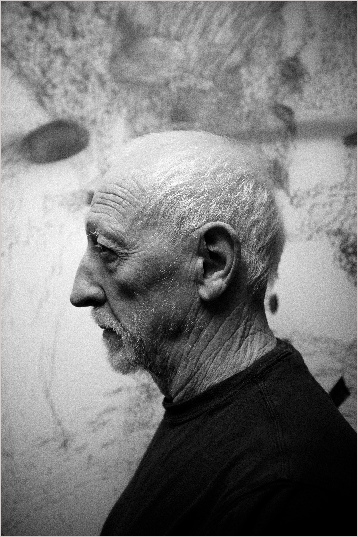

Lance Austin Olsen

Photo: Jamie Drouin

Lance Austin Olsen ‘Blue Drift Hotel Londres’

Lance Austin Olsen ‘The Fall’