Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

at78 Jamie Drouin & Lance Austin Olsen - sometimes we all disappear

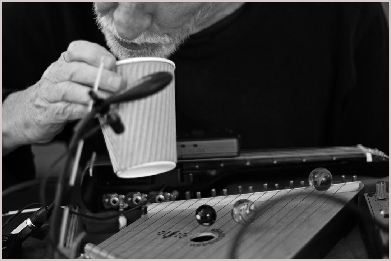

Jamie Drouin - suitcase modular & portable radio

Lance Austin Olsen - amplified objects and audio cassettes

Recorded at Lance Austin Olsen’s studio, Western Canada, August 2012

One track: 46:00

Jamie Drouin and Lance Austin Olsen started working together as a duo in the mid 1990’s when they met in Victoria in Western Canada. They set up their own label Infrequency Editions through which they have released several excellent CDs. In addition to their electronics-based musical work, both are active as visual artists.

Interview with Lance Austin Olsen

Which came first, the art or the music? And do the two things feel closely linked or like separate practices?

The visual art came first. I was accepted at Camberwell School of Art in 1959 when I was just 16. I had always been a shy kid that liked drawing and painting and hated actual school, so being put into an environment where the teachers were amongst others, Frank Auerbach, RB Kitaj, Patrick Proctor, Henry Inlander, Michael Rothenstein and above all Euan Uglow, whom I credit for teaching me how to look and draw with his meticulous and sometimes irritating methodology. This was the best that could ever have happened to a sixteen-year-old misfit.

When I got married and moved to Western Canada and had a first child, there was no money for extravagances like record players and buying records so I did not hear any of the artists from the 70’s and most of the 80”s and to this day don’t know who most of them are or what they sound like. I spent my time listening to the environment that we lived in. I don’t own an IPod and I NEVER walk around with earphones listening to music at the expense of the wonders of my actual environment.

We lived on a small island in the woods for a number of years so I became very fond of the quiet punctuated by the occasional chain saw.

I got involved in audio work and experimentation in about 1997-8 and view it as painting and drawing with sounds. It is now intertwined with my visual arts practice and I now could not imagine one without the other.

The way you describe listening to your environment rather than records is reminiscent of Cage’s writing, but I don’t suppose you were reading him either….? And were you listening to music of any sort before you started experimenting with sound in the late 90’s?

When I was at Camberwell art school in the late 50’s early 60’s the dances were strictly traditional jazz and I really liked, and still do, George Lewis and Bunk Johnson and collected a fairly substantial amount of albums by King Oliver and Louis Armstrong and all the early bluesmen such as Blind Blake, Lemon Jefferson, Ma Rainey and my favourite of all time Blind Willie Johnsons “Dark Was The Night, Cold Was The Ground.” I still have all these albums and all the John Coltrane and Monk and Johnny Hartman albums that I loved. I also loved Verklärte Nacht, op 4 for String Sextet by Arnold Schönberg; it was dark and interesting and my visual work had also become dark.

Suddenly it seemed R&B took over the whole art school circuit and we went to Eel Pie Island to find that traditional jazz was basically a thing of the past, ironic, since it was always a thing of the past. Like all my contemporaries we went to the Marquee and the Station Hotel to see the Stones and later when the Crawdaddy club moved, the Richmond Athletic club to see the Yardbirds and all of Georgio Gomelski’s collection of bands.

The Beatles hit the scene at the same time. Their music was both danceable and seemed different. During this whole period I had become more and more interested in classical music, particularly Schönberg and late Stravinsky, and modern jazz , as well as my ongoing love for the old blues singers.

I left for Canada at the same time as the release of “Sgt Pepper Lonely Hearts Club Band” and I still have only a mono LP of the work. The music I listened to in Canada was pretty much what was on the radio. Whatever was on was what I listened to. When I was driving around I would often put the radio on auto scan and it would play 10 seconds of every station it could find. It drove my wife crazy. I was not reading John Cage, I was reading Gurdjieff and Ouspensky and later Suzuki Roshi and trying to raise children and earn a living without abandoning painting.

In the mid 80’s I bought a record player and began to play all my great albums again. I also became fascinated by the work of Friedrich Jurgenson.

So, Trad Jazz, blues, R&B, Modern Jazz, a Radio on auto scan, chainsaws in the quiet of the woods, Schönberg and Friedrich Jurgenson, the recipe for an audio feral child.

In the mid 90’s a young man called Jamie Drouin showed me a piezo microphone. I taped it to a copper plate that I was working on, and there it started.

So how, where and when did you meet Jamie? And was he already part of an existing experimental music scene, or were you pretty much on your own?

By 1984 I was totally pissed off with the whole art scene, self-serving curators, whining artists the whole thing. I looked around to see what else I could do, when it struck me that instead of putting pictures on the walls of empty buildings and hoping to sell them, I would somehow build a small luxury hotel with pictures on the walls to look at and sell the beds nightly. I won’t get into how I did this with just credit cards and bullshit, but I managed to open a small luxury fine arts hotel downtown in July of 1986, there were no hotels like this in Victoria at that time. I ran this with my wife for 9 years.

The important thing here was that we would prepare breakfast for all of the rooms which entailed us getting up at 4a.m. 7 days a week and working in the kitchen. We never spoke, it was quiet, just the sounds of the building waking up. It was wonderful. In 1995 after an extended legal battle with a partner that I had brought to expand the business, my wife and I walked out with nothing.

Well, I had no money and I needed a job, and the local art gallery needed a part time assistant for its art rental department. They hired me, and here I was working in a place full of people who pissed me off. A part-time, evening security guard started to talk to me, and a few weeks in I saw his photographs. They were fantastic. That is how I met Jamie.

During our conversations he suggested that we made some short movies based on some writings I had done from conversations heard on a bus. Riding the buses was like being trapped in a Samuel Beckett play. I would listen and scribble down fragments of conversations. These were actually the beginnings of what ended up as notes for an 88 page score called “Craig’s Stroke”, but at that time they were just interesting fragments. We made a couple of videos and showed one as an installation called “Next Stop”. I had submitted it to a guest curator at the gallery under a false name and they loved the piece. When they found out it was the work of Jamie and I it was too late to backtrack, but a new policy forbidding staff to submit work for exhibition was put in place.

Jamie left the gallery to work as a website designer for a year and during this time he approached me with the notion of doing a series of audio performances in a local commercial gallery. Given that it has always been my belief that I could do pretty much anything I set my mind to, and given my belief in Jamie’s abilities, I said, what the fuck, the worst that can happen is that it will all be shit. So that’s what we did.

This was the first venue for experimental audio in Victoria; nobody was interested, so we had to do it.

In spite of that small starting place, through your releases on your and Jamie's label Infrequency Editions, you've become at least a little known in experimental and improvised music circles, and have now collaborated with several other musicians as well as Jamie. Do you now feel part of a 'scene' musically, or does your location in Western Canada - far from the big centres of experimental music globally - still mean that you still feel pretty isolated in what you're doing?

Well I do live on an island off the mainland of British Columbia, Western Canada, so the isolation is felt and actual. The closest physical collaborator I have now is Mathieu Ruhlmann, and more recently Joda Clement. Both of these gentlemen live in Vancouver, which is a one hour bus ride and a two hour ferry ride then another one hour bus ride for me to get to the music school where we record in downtown Vancouver. As you can see, that is an eight hour round trip plus 5 hours of work time. It makes for a long day and I can’t do this more than maybe 4 or 5 times a year.

Jamie Drouin now lives in Berlin and that is even more difficult, so I guess the short answer is ‘yes’ to being isolated, but I’m fortunate to be able to work via computer with some wonderful artists in this great period in time.

So given that Jamie now lives in Berlin, how did the recordings, which became your new CD ‘sometimes we all disappear’ come about? And what is the significance of the title?

Jamie and I spent about 3 years working twice a week in my studio, experimenting with various sounds and approaches and recording everything. My view has always been that the recordings we produced in this intense period were the raw material for years of future albums. This has its parallel in the tins of paint I have in the painting studio. I have always believed that if you have 3 colours you should be able to produce a lifetime of works using these same colours, and never become repetitive.

We had also done a number of edits using the material and laid out a number of albums. As time passed we revisited these with different ears, which produced surprises and unconsidered directions. Both of us are people that like working in a reductive way. For myself, putting in everything, then slowly removing almost everything, has long been an approach that I am comfortable with.

This particular work had been sitting on my computer for a couple of years when Jamie asked if I could look through our material and see if there was something I thought needed to be reconsidered. I liked this work a lot but it needed things to disappear so that the overall work had breathing space and could gain clarity. I edited, then sent it to Jamie. He commented, I edited and sent it back, and he mastered it.

Jamie has disappeared for a time from my physical environment, forcing us to reconsider our collection of sounds to produce new work. This for me is a wonderful opportunity to find the new hidden in the not so new. If material was good in the past it does not become un-good in the future, but we find differences in the material through our experiences. Sometimes we all disappear.

Yes, it’s certainly the most ‘reduced’ work I’ve heard from your duo so far. One thing I love about it is that it goes beyond the standard idea of a musical performance, as if the sounding passages are intermittent windows on an intimate, self-contained conversation, taking place independently of the listener. And the long pauses make it possible to sometimes forget that the music’s playing at all, as if it’s just hovering on the edges of space and time, sometimes audible, sometimes not. Do you see it like that too?

Yes, that is certainly close to my view and I agree that our fragile lives are hovering on the edges of space and time.

I spent about 10 years in one of my day job lives, installing paintings and drawings into gallery spaces. One of the things that I noticed over the years was how much more interesting the space between works is than most of the works themselves, so I would always try to do the best for the artist in the process of displaying the works. This is not a new idea, but the wall can be seen as a work itself and the arrangement of the paintings as small windows relating to each other and to the space overall, but with individual experiences contained within each small window, which may or may not relate directly to the previous experience. As one moved through the space a retained but fading memory of the work at the periphery of vision interacts with the approaching work, creating a new experience probably never envisioned by the artist. This approach allows quiet reflective periods after experiencing each work before arriving at the next, with a refreshed mind.

At each fresh listen the album brings back moments of deeply hidden memories, including times spent sitting in cafes and on buses allowing fragments of conversations to drift in and out of my consciousness. Still they remain ungraspable, the edges of a daydream, touched upon, then suddenly lost once again.

The original live recording sessions with Jamie always had an intuitive structure. We both knew when to stop, when to allow the other to come forward and to recede, when to play, when to sit in silence. The editing process was pretty much the same. We both knew from the first listen, and further edits, where we were going with the work. Our brief conversations always clarified any moments of uncertainty. In some unfathomable way it brought back those early mornings years ago when my wife, Robin, and I would not speak in the hotel kitchen but move through our tasks with harmony and certainty. One’s daily life tasks and trials often bring clarity to otherwise mysterious events.

Finally, as Jamie pointed out in our discussions, this album focuses on time in a very different way than any of our previous works. The notion of a performance is pulled apart and we are left with “pieces” which can either be seen/heard relating in linear passage of time, or each can be considered distinctly, as if holding a colour swatch to the wall of your home to see how the wall is briefly influenced. Our use of silence in this album is less about tension and more about distance, forgetting, and then perhaps remembering again.

Reviews

“Jamie Drouin on suitcase modular & portable radio and Lance Austin Olsen playing amplified objects and audio cassettes have fashioned a series of tiny sound assemblages spread over 46 minutes of silence.

Played at a low volume in a room (not on headphones), this disc will meld with the quotidian sonics of your environment and make it difficult to separate "foreground" from "background". You may easily forget that it is playing and be surprised when it's quiet sounds bloom. There is no long-term form in evidence, as the memory of what's gone before is difficult to maintain. One is left to experience each event as a singularity, a small bump or scrape mark on a vast uniformity.

The sounds spread over this canvas are as interesting as they are brief: soft hisses, single clacks, swelling bass blobs and metallic scrapes sit apart from each other, conjuring questions about one's hearing. Is that a tap left running? A neighbor's home repair? In some rooms I dare say this collection may be overwhelmed by traffic and airplane sounds, but it's quiet comments sit well here in the desert.”

Jeph Jerman, Squid’s Ear

“Composition is often understood as a process of adding, mutating and organizing sounds, but with artists like James Drouin and Lance Austin Olsen is demonstrated that it is also an art of dispensing, dissolving and reducing elements. Sometimes we all disappear, perhaps everything does, melted in memory in order to be, as if listening to what is sounding consisted on forgetting what is sounding; even the listener forgets himself, moves on its own transience. In an improvised ritual, the mentioned artists exhibit “silent” distances that not only foster the act of hearing but lead to an intimate encounter with the sonic forms as such, in this case delivered from a modular synthesizer, some radio frequencies and subtle micro-appearances of various objects; extended in such a way that challenges the notion of “piece” as it is ejected from its space and gets renewed as every sound (dis)appears in scene.”

Sonicfield blog

Discount price £5