Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

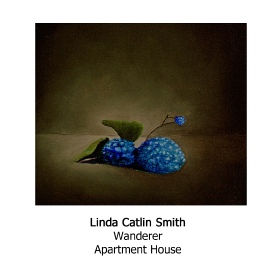

at130 Linda Catlin Smith ‘Wanderer’ played by Apartment House:

Philip Thomas (piano)

1- Morning Glory (2007) 12:43 Anton Lukoszevieze (cello)

2 - Music for John Cage (1990) 3:28 Mira Benjamin (violin)

3 - Stare at the River (2010) 12:21 youtube extract Heather Roche (clarinet)

4 - Knotted Silk (1999) 4:33 Nancy Ruffer (flute)

5 - Sarabande (2010) 8:35 James Opstad (double bass)

6 - Velvet (2007) 14:59 Chloe Abbott (trumpet)

7 - Wanderer (2009) 12:03 Simon Limbrick (percussion)

8 - Light and Water (2010) 6:01 youtube extract George Barton (percussion)

Mark Knoop (piano)

Jack Sheen (conductor)

Jack Sheeen (conductor)

Mark Knoop (piano)

8 - Light and Water (2010) 6:01 youtube extract George Barton (percussion) Mark Knoop (piano)

Jack Sheen (conductor)

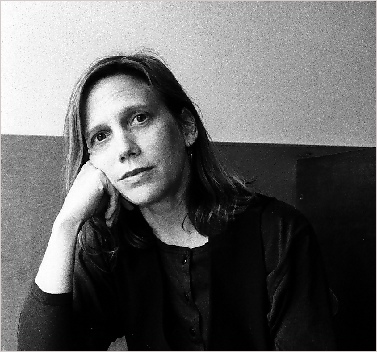

Interview with Linda Catlin Smith

Extracts from an extended interview with Linda Catlin Smith in the booklet which accompanies the Canadian Composers Series CDs

You’re not from Canada originally, so how did you come to settle there, and what was your musical training?

I was born in New York and lived there for my first 18 years. My mother was a piano teacher so I started reading music before I read words - just from sitting with her at the piano. I was a bad piano student - I preferred to make up things rather than practice, and the piano always sounded so beautiful, I liked to make up my own pieces, starting when I was about 9 or 10. I began my training in composition in high school. I went to an alternative high school in Greenwich Village called Elizabeth Seeger School. There were only about 50 students in the school. In my second year there, they hired a new music teacher, composer Allen Shawn. There were very few music students, so I had a lot of time and instruction from Allen - he was very supportive of the composer I was trying to be. After high school, for my first two years of University, I went to the State University of New York at Stony Brook, as it was close to Manhattan and had many great NY performers teaching there. There was no undergraduate program in composition, so I attached myself to some of the graduate composition students, who looked at my work from time to time. It was there that I met several Canadian grad students: Christopher Butterfield and Owen Underhill. Christopher and Owen became good friends and they both urged me to go to the University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada, which had a very strong composition department. In particular, they thought I should study with their teacher, Rudolf Komorous. I went there and loved the school, and the place, and ended up staying on to complete my master's degree. It was one of the best things that I could have done for myself, though it meant having a long distance relationship with my boyfriend, percussionist Rick Sacks (pre-internet!). But we have been together ever since, so it all worked out. Then, after graduating, I ended up moving to Toronto. That was because Rick had joined a rock band with Christopher Butterfield (the same one) in Toronto. So I started life after university in Toronto. The contemporary music scene was in a growth period then, so we both just got busy. And we are still here...

What kind of music were you most interested in, and writing, when you were at University?

I was interested in everything, I was always curious about new things. In high school, I was very attracted to Stravinsky, Ives, Bartok and Satie. At SUNY Stony Brook, I had a job ordering recordings for the music library, so I was able to listen to music from all over the world that was completely unknown to me. The library at the University of Victoria was also very good, and students were allowed to take out 6 records (LPs!) per week, so I would browse the stacks, bringing home armloads of recordings. The most influential pieces for me were John Cage's String Quartet in Four Parts from 1950, Anton Webern's Symphony Op. 21 and Morton Feldman's False Relationships and the Extended Ending, the only Feldman recording they had at the time. I listened to them over and over, as well as some early music recordings, particularly the music of Francois Couperin, Josquin des Prez and Guillaume Du Fay. When the composer Jo Kondo came to teach for a year at Uvic, I had my ears completely opened by the course he gave on traditional Japanese music, especially Gagaku. Kondo's recording of his piece Standing was a complete inspiration to me. Kondo, Webern, Feldman, early Cage, Gagaku – these were my worlds.

The music I was writing was generally exploratory: I toyed with 12 –tone pitch methods, and other systems and processes. And then one year I had a key moment: I had written a chamber piece that was filled with complex rhythms and gestures, all derived by rather academic means. I just didn't feel attached to it at all. So I scrapped it entirely, and started over, writing only what I could hear. In the end, writing by ear made me feel more connected to what I was doing. The works became simple, more harmonic, and very much focused on orchestration and colour. In those years, I wrote my first string quartet, my first orchestra piece, and several chamber works including my first piece for Baroque instruments (soprano, Baroque flute and harpsichord), a sound world I love to this day (recently I wrote ‘Ricercar’ for Baroque cellist Elinor Frey, and a Baroque string orchestra piece for Early Music Vancouver). In those years I also cemented my continuing relationships with other composers who have become friends - artistic confidantes; having them in my mind makes the world of composition less solitary.

So do you still compose completely ‘by ear’ with no system at all?

I would say that composing by ear is my system. I think of this as speculative composition - that is to say, I don’t plan everything in advance; rather, I respond to the material at hand on a moment-by-moment basis during the course of the creation of the work. This is not improvisation – not just writing whatever comes into my head, it’s not “anything goes”. It's a mode of working that calls for intense scrutiny, questioning, experimentation and a kind of ruthlessness in the process… This way of working– this system – is a combination of intuition and reflection, and most of all, listening. Behind it all, I am always wondering: what if…? What if it was longer, what if it was thinner, or higher, or brighter or more fluid…For the longest time with each work, I am unsure of what I am doing. But for me, when I don't know what I'm doing, I feel I am on the right track.

There is a strong group of quite individual and distinctive composers in Canada, but they don’t seem to form a ‘school’ as such.

While not forming a school exactly, there are quite a few composers who studied with the Czech-Canadian composer, Rudolf Komorous, and there is a kind of connection between us. John Abram, Martin Arnold, Christopher Butterfield, Allison Cameron, Anthony Genge, Steven Parkinson, Rodney Sharman, Owen Underhill – this is just a selection of the variety of composers who studied with Rudolf and are currently active as composers. Rudolf treated each of us as an individual – our lessons were all quite different – but we all were encouraged and challenged by our lessons with him. There is nothing really definitive to tie these composers together in terms of style; perhaps it's more of an adventurous approach, an experimental bend of mind…and maybe a willingness to work outside of the mainstream, whatever that is.

I've often felt that Canadian composers have a particular freedom in terms of style and aesthetics. I've always felt free to explore music in my own voice with no pressure to fit in. I think Canada is so vast, with so much distance between cities, and it is so far from most other countries; we are largely unexamined by the world, for the most part, left alone to explore and experiment. Maybe it means we have a harder time having our work appear on the stages of Europe or the US…but I have the sense that I can work unfettered, without having to fit into any particular aesthetic frame. Composers such as Ann Southam and Claude Vivier and Rudolf Komorous – to me they exemplify artists who persevered in their own particular artistic path. We are just out there working in the wilderness, so to speak.

Does that sense of wilderness affect the sound of your music at all?

I don’t think the idea of 'wilderness' affects the sound of my music as much as it relates to a kind of compositional approach – the move into new territory, trying new things, not knowing what the material really is, or even if it is anything at all – a step out into the wilderness of one's own imagination. In terms of sound, perhaps the wilderness aspect lies in the places where I let things overlap and overlay, as in the Piano Quintet, where melodic lines become entangled, like an overgrown garden.

I grew up in a culture in which modernism and the avant-garde were highly valued, and they were often defined in opposition to romanticism. Your music seems to combine elements of both aesthetic tendencies. Do you situate yourself in relation to those broad aesthetic categories?

I have never felt attached to romanticism in its broad strokes; for me, it seems too much about expressions of the artist's feelings, and I've never felt that I'm involved in that. I believe all music has an emotional component – every piece of music has its own tone, or subtle shade of feeling – but I never feel I start from a place of self-expression. Rather, the tone or emotion is there as a kind of background or atmosphere that surrounds the material I'm working with. I'm not making music that is about myself; I am making music so I can lose myself.

[........]

How have you survived financially as a composer in Canada? Presumably you can’t survive solely on commissions, so what other work have you done? And has that other work been an annoying distraction, or do you think it has affected your composing in a positive way?

I've always had regular jobs to support myself. After university I worked as a waitress, meanwhile putting on occasional concerts in an artist-run art gallery. That led to the art gallery hiring me as an administrative assistant for a few years. I continued to put on concerts there, and at one of them the Artistic Director of Arraymusic in Toronto asked me to join Arraymusic's board of directors. Within a year or two, I was their new Artistic Director - a dream come true for any composer. I learned as much from rehearsals with those musicians, and from the other composers, as I had learned in university. I left Array after 5 years, and a few years later I was offered a part-time position at Wilfrid Laurier University, and I have been teaching composition two days a week ever since. Each of these places of work taught me something helpful: I learned so much from being around visual artists at the gallery – the way they talk about their work, their exploration of material, and the experimentation involved (all composers should have visual artists in their lives)… My teaching at the university has been especially helpful as it forces me to think and articulate ideas in a clear way. I also had to learn how to keep my composing going while working at other jobs; most composers I know have had to support themselves with other work, so we become very adept at managing our schedules, and protecting whatever spare hours we have for our work. Eventually, I found that I am quite flexible about my composing schedule; give me a quiet hour with my piano and I can usually get something done.

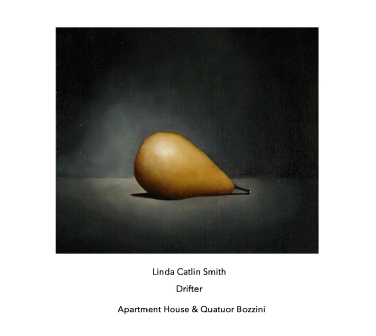

Linda Catlin Smith

For special offer on all 10 CDs in the Canadian Composers Series, go here