Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

at123 ‘tse’

Cyril Bondi - harmonium & pitch pipes

Pierre-Yves Martel - viola da gamba & pitch pipes

Christoph Schiller - spinet

I - 10:06

II - 10:08

III - 9:05

IV - 7:42

V - 9:48

Interview with Pierre-Yves Martel

How did this trio come about?

I first met and played with Cyril Bondi in 2011 in Montreal,

Canada, in a quartet comprised of Cyril, myself, d’incise and Dragos Tara. We stayed

in touch afterwards and followed each other’s work. In the spring of 2017, Cyril

wrote to me asking if I’d be interested in recording something with Christoph Schiller

and him. It turns out I’d been in contact with Christoph for couple of years and

we’d planned on playing together, so I was very pleased to receive that invitation.

Tell

me about the recording session. Was the music planned at all, or is it freely improvised?

The

recording session took place at the Insub.studio in Geneva. Nothing was planned musically

beforehand and it was the first time we played together. If I remember correctly,

we played a series of six 15-minute improvisations, two of them completely improvised.

For the other four, we decided on a series of pitches which would determine the form

of each piece. Even though Cyril, Christoph and I share a similar approach and aesthetic

when it comes to improvisation, I think we were all surprised by how naturally and

effortlessly the music happened.

I guessed there must have been some kind of agreed selection of pitch material. Why did you do this, and is that a method you have used before when playing with other improvisers?

We started off the recording session with a free improvisation. Christoph then proposed the idea of structuring the pieces with pitches, which is something he and Cyril had done in the past. From a metal box, Christoph took out small, square-shaped pieces of paper with two, three, or four pitches written on each of them. We then ordered a series to determine the form of each improvisation.

The idea of creating parameters to take the music in certain directions is a constant in my work. I hadn’t really used pitches the way Christoph did, but in my recent solo work for example, I’ve limited myself to using only bowed natural harmonics and left-hand pizzicati on the seven strings of my bass viol, in conjunction with certain pitch pipes and harmonicas. The goal is to feel totally free within a strict, imposed framework.

That’s interesting. I know that you’ve worked with improvisation a fair bit, but this suggests that purely free improvisation – with no parameters at all – is not particularly interesting for you. Is that true?

Even in situations where there are no agreed-upon parameters, I find that I end up imposing some on myself. Repetition is an important element of my work, so that in itself brings in a kind of order or system where certain forms are cycled and developed over time within a performance. Speaking personally, I find that music requires a kind of implicit order, though this implicit order can consist of the barest rules imaginable. You need something to contain and channel the chaos of creation.

What does the title 'tse' refer to, and why did you choose it?

The word tse comes

from a mountain dialect spoken near Geneva. It means “here.” When we were deciding

on a title for the disc, we each had ideas, but for some reason tse spoke to all

three of us. I guess it reflects how the whole thing happened so quickly, the three

of us being there, sharing these intimate moments.

What’s your background in music, and why the viola da gamba?

I started out playing electric bass, then moved to double bass in my late teens as I got interested in jazz. I then studied classical performance and composition at the University of Ottawa. I would say that apart from my university studies, which focused on orchestral playing, I’ve been something of an autodidact. Improvisation has been fundamental in my approach to learning and playing, from when I was a child until today.

I was able to borrow a viola da gamba in my last year of university and taught myself the instrument and its repertoire. It was the timbre of the instrument, the complexity of its gut strings and its untapped potential for contemporary repurposing that made the viola da gamba so compelling to me. It wasn’t long until I abandoned the double bass to commit myself to this instrument.

Yes, I also feel that there’s a huge and largely untapped potential in using early instruments in experimental music contexts. Can you say a bit more about your thoughts on this and projects that you have worked on?

Early musical instruments by their nature have a stronger materiality than their modern counterparts. What I mean by this is that whereas modern instruments are designed to eliminate or cancel out all those secondary, incidental noises that occur as a result of making music on a material object, early instruments preserve those noises. In fact they put them on a level playing field with the instruments’ intended sound. The microphone picks up not just the sound that you’re playing, but also the noises the instrument produces as you play it. This is interesting from an experimental perspective because it vastly expands the palette with which I am working.

With the viola da gamba, there is the added advantage of a high number of gut strings, which increases the harmonic qualities and again, multiplies the possibilities at my disposal as a performer.

Aside from tse, the only project of mine in which performers other than myself used early instruments was Plans d’immanence (2011). That project included a baroque guitar, a hurdy-gurdy, recorders, a baroque trumpet and early percussive instruments. The idea was precisely to work with the various instruments’ secondary or incidental noises. The musicality of the pieces owed as much to these other sounds as it did to the notes being played. The downside with Plans d’immanence was that the concept came before the performance. With tse, we didn’t have conceptual conversations beforehand; we just had the same implicit idea going in, or very similar ones, and that served to increase the synergy and spontaneity of the music we created.

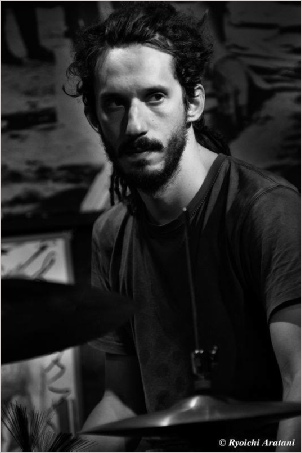

Pierre-Yves Martel

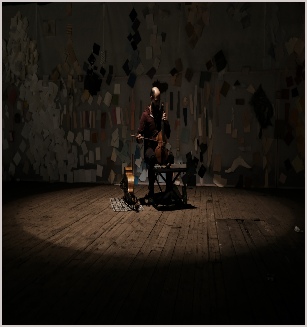

Cyril Bondi

Christoph Schiller

Reviews

“This album places Bondi in a more intimate a context with the Quebecois Pierre-Yves Martel and the German Christoph Schiller. The instrumentation on this album is notable in its own right. All three musicians play early musical instruments: Bondi the harmonium and pitch pipes, Martel the viola da gamba and pitch pipes, and Schiller the spinet. Most of the tracks on this disc are based around a framework of pre-selected pitches. Others are freely improvised, though it is difficult to distinguish which these were. The result is a series of intricately textured and meditative tracks. In ways, this ensemble resembles a stripped-down IMO.

As Martel notes in an illuminative interview posted on the Another Timbre website, the title, “Tse,” is a Genevan word that simply means “here.” He then explains that this may reflect the suddenness and happenstance of the meeting of these three musicians. However, there seems to be more to it than that. The tracks almost bleed into each other. Each has its nuances and unique beauty, but one must listen closely to find this repressed dynamism. “Here” may also reflect the nuances of place and music. The pieces resemble each other in their slow, subtle, droning beauty. They also, however, represent discrete moments of musical inspiration and creation. In that sense, they reflect the singularity of being present in any moment, setting, or piece. The effect is entrancing and, at times, disconcerting. “Tse” actually offers six “heres,” and shows that even the superficially mundane or old can be pregnant with new and provocative possibilities.”

Nick Ostrum, Free Jazz Blog