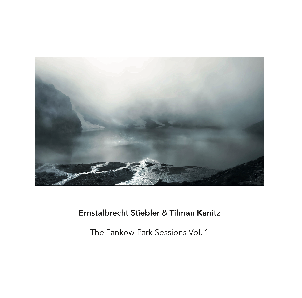

Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

at189 Ernstalbrecht Stiebler & Tilman Kanitz

‘The Pankow-Park Sessions’

Recorded during Covid lockdown by Tilman Kanitz at his studio in Berlin.

Interview with Tilman Kanitz

Could you tell us how and when your duo with Ernstalbrecht came about?

At a festival for North Indian Classical music in Calcutta I was impressed by the extensive “tuning up” process of the musicians. I thought of Ernstalbrecht and wrote to him, suggesting that he should write a cello piece for me. A couple of months later, at the concert in Berlin where I premiered this solo, he asked me if I would like to improvise with him. That was in early 2019. Since then we have been meeting, almost weekly, to improvise and record ourselves in my studio in Berlin Pankow.

How long has each of you been playing improvised music?

Ernstalbrecht says he started improvising music with me, shortly before his 85th birthday. I started improvising when I was 5 years old, together with my sister. And since then, improvising music on the cello, the piano, and other instruments has played an important role in my life. But it’s only with Ernstalbrecht that it has become a regular practice, and this is the first release of our improvised music for both of us.

I find it incredibly impressive that anyone can start improvising at the age of 85, and immediately do it so well. But are you improvising completely freely? To my (unmusical) ears, there seems to be some kind of modal system underlying the music. How much discussion, planning and preparation do you have before each session?

When we started improvising together it was a musical dialogue right away, with no discussion, planning and preparation. The only remark I remember is that at one point I made a request to play less notes. And on another occasion Ernstalbrecht asked me to play longer notes. These were the only two moments in our work when it seemed necessary to formulate one’s wish to the other. Despite that, each improvisation is simply accepted by us, and starts without any previous arrangement of any kind. The only intention is to meet at a certain time, and play, alternating who begins. We develop the pieces in real time with no revisions, trusting in the full breath. The music is predetermined by what we did before, trusting in the now, the expansion in the now, the play in the now. We listen to the recording two or three times, then play again. When we write to each other, we comment only on positive things, never mentioning what doesn’t or didn’t work, but communicating and building only on what did.

I think of Ernstalbrecht's composed music as being wonderful, but quite austere. Yet the music you improvise together seems quite different - much more emotionally-driven, almost romantic....?

Ernstalbrecht’s composed music is meant to be played in public. The idea is to unburden music from emotions, and to enable the listener to create inner spaces, in order to encounter oneself. It is a highly individualized musical experience, unique for each listener. Our common music, on the other hand, is not meant to be played in public initially. It is our private dialogue about each of our musical histories. Ernstalbrecht says that, for him, our improvisations are a way of making it possible to deal with music history. Maybe improvising is for both of us simply the echo, the memory of a Mozart Sonata, or Liszt's Petrarca Sonnet 104, or classical Persian music we listened to.

Yes, Ernstalbrecht described your music as “a new freedom to handle tradition” and says he is primarily using fifths and octaves. Your duo does seem to engage with melody more than other improvisations I listen to. Were you surprised that the music took that particular direction?

To be honest, I am surprised each time I listen to our music. I am surprised by these hints of melodic fragments, woven into the progressions. Sometimes they sound like extremely stretched particles of musical sediments, the remnants of traditions. At moments I sometimes think “this reminds me of…” and then the music already moves on and leaves that memory again. Most of our tracks are a journey. A journey with an unexpected destination, or rather no destination, merely a stream that often just fades away, leaving the listener unable to understand: how did I get here? And along the way, those melodies are blown through the structure, moving things forward.

I didn't know your music until Ernstalbrecht sent me recordings of your duo. Can you describe your background, and what kinds of music you play in other contexts?

I have studied western classical music, especially the cello, since I was very little. At the same time, I listened over and over again to all kinds of old jazz records. And eventually, as a teenager, to Webern, Cage and Feldman, North Indian classical music, Lachenmann, and so on. At one point I became a soloist in an opera orchestra, playing Wagner, Verdi, Puccini - and finally I became the Artistic Director of the Berlin Solistenensemble Kaleidoskop. With this unique group of musicians, I had the wonderful opportunity to experiment with combining curating music and composing it. I was creating new works based on western classical music from 1400 until today. In the past three years I have been mainly working on my own music, and am invested in researching the relation of specific frequencies and different states of consciousness. At the moment I am listening to, if anything, sine waves, Pygmy music, Z. M. Dagar playing the Rudra veena, and, for research, any traditional music.

I hadn’t thought of Indian music, but I can see that there’s some connection between the contemplative, interiorised explorations of your duo with Ernstalbrecht, and a lot of the ragas I’ve heard. I think it’s good to have this relationship without attempting any kind of fusion or crossover music. Do you use other traditional musics in similar ways in your current work as a composer?

My work is based on dialoguing. That can be with someone, like with Ernstalbecht. Or it can be with an artwork, like it is in a series of piano pieces, based on my reflections on an ancient Egyptian artwork. Or it can be a remix of a traditional piece of music for Daegum, the Korean bamboo flute, bringing out the areas offside the audible, bleaching the music, leaving us with modulations of white noise and a crackle here and there, unrecognizably carrying the horizontal energy of the original.

Or it can be the encounter with an animal in the wilderness, the whistling sound this animal produces, while looking into my eyes. I recorded that sound, because I was fascinated by it. And then, using different algorithms, prolonged this 1/10th of a second long sound of the animal, communicating with his fellow animals. I zoomed into this extremely fast sound progression until it was 20 minutes long. That, with all its digital artifacts, was then my material. Still carrying the intense energy that made me record the sound in the first place. The work was then, to bring out all the interesting rhythms, curves, even melodies, that are contained in this material, to make space for all the unknown forms, shapes and entities, to keep the initial dramaturgy and maybe the meaning and function of that sound. This is an example of how I like to work, entering into and interacting with the unknown, dialoguing with it and together finding a path through the endless possibilities. It is all the reflection of the music I have listened to, the music I have learned from, and am inspired by.

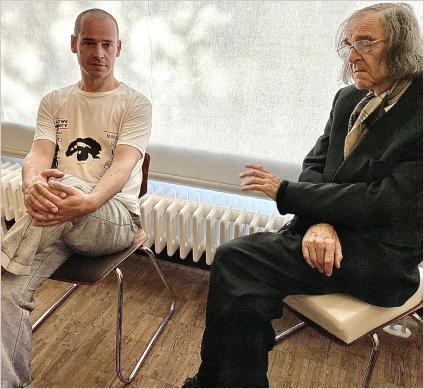

Tilman Kanitz & Ernstalbrecht Stiebler