Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

James Saunders interviewed by Dominic Lash

DL: Could you explain a little about the #[unassigned] series and how that turned into the assigned series?

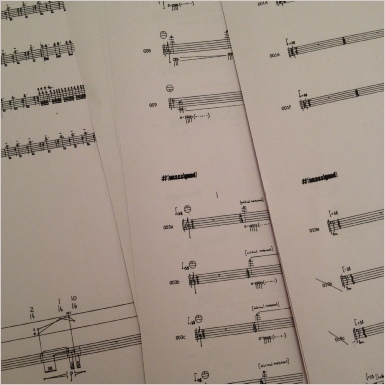

JS: #[unassigned] was a project I worked on from late 2000 to mid-2009. It changed quite a lot over those nine years, but the essence of it is a pool of quite a few short modules for solo instruments. Some of these were short pieces that were gestural, mostly using extended techniques, and longer drone modules that were scalable to different durations. So a mix of shorter, event-based material and longer sustained sounds. So that was the basic material and then every time we did a performance I'd make a new arrangement of that material. So typically I'd take some existing modules and then combine those with some new ones, and make a new time structure for the players to place those sounds in. So the pool of modules was always being added to, and then each performance of the piece was different, so the performance on one day by one ensemble would have a certain arrangement of material and then a month later, different people, different place – or even the same people, different place – would be a different grouping.

DL: Was that most of your compositional activity at that time?

JS: That was the only thing I did for nine years. I didn't do anything else. Although that's not strictly true because there were some versions within the project that with hindsight were not a very good fit. They pushed that framework a little bit and subsequently I've actually remade them into separate pieces. There's a piece called with paper which I did with Tim Parkinson in about 2006. The score is printed on the paper. We did that then as an #[unassigned] but subsequently I've made it into a separate piece because it didn't really fit within the framework. And I think one of the reasons I stopped doing #[unassigned] was that around 2007 to 2009 I was increasingly wanting to do other things and it was becoming just a bit automated. I just came up with a time structure and then just rearranged things I'd already made. I wanted a bit more of a challenge as much as anything, so I started doing other things. So I stopped that in 2009, formally as a project.

DL: But now you've revisited it?

JS: I suppose, and this is going to sound like an episode of W1A, the legacy of that project was that these pieces were performed only once - that was it and they were gone. I think I made 175 or so versions over nine years, and some of them I quite liked! And it was a shame that they were gone, in a sense. So what I did around the end of finishing that project was look back over those versions and chose my favourite ones, the ones that I think worked the best, and made those into a separate series called assigned, and they are then re-performable. And a few of them have been done again. It's really just those versions so it's exactly the same music but just that you can play them again rather than you can't, that was the distinction. And you yourself have played a double bass one, which was written for Chris Williams.

DL: Around the time I was doing my PhD I was really interested in #[unassigned], so it was quite interesting for me to see you come back to it. At the time there were all sorts of things that resonated a lot with me, partly that thing about the fact that any composition is somehow arbitrary. No matter how systematic, there's some arbitrary point where it's just "I've chosen this because..."

JS: As Tim Parkinson says, and this is one of my favourite comments about music, "It's all just made up."

DL: And then how that relates to what a composition is, whether it's a thing which is repeated. For me it relates to improvisation as well because either there's this unique performance or there's this piece which is somehow unique which is repeated. What thoughts do you have now looking back, or in relation to what you're doing now with the assigned series, about the difference between the fixed and the unfixed?

JS: Well it was a really, really odd thing to do, because it was six years between finishing the #[unassigned] project and making this version. Basically, Simon Reynell asked me and I guess I'm at a stage where the work I'm making is mostly process based but I still enjoy engaging with the aesthetic quality of sound, and trying to manipulate that. So although I've moved away from a focus on specific sounds in a number of things I'm doing it's something that still interests me of course, so it was a good opportunity just to re-engage with that. I wanted to see what that felt like again, really. So that was really my reason for doing it rather than not doing it. And then in actually making the piece it was such an odd experience because at the time when I was making the #[unassigned] series I was still actively making new material and the project was developing a little bit in terms of the sounds I was using, and textures in particular. So it felt like a living project, whereas here it felt more like a revisiting a museum exhibit. Looking back it felt a bit like archaeology perhaps.

DL: Old photos of yourself.

JS: Yeah, because the material itself hasn't changed, it's only the arrangement of it, working at a structural level in terms of making pieces. I was using material that I wrote in about 2001 and later, so it's reengaging with me of fourteen years ago and using that material.

DL: So did you write any new material?

JS: No, no new material at all. No, actually that's not true because I used shortwave radio, and I didn't use that before. I had used longwave radio before, but shortwave radio was something I wanted to play with.

DL: In the process of doing it and then going back, making it and listening to it, have your thoughts changed about this relationship between uniqueness and individuality?

JS: Yeah, in that now I'm not so hung up on that. I think I'm quite happy with it being a piece that's fixed and repeatable. I think I'm less precious about that. In the original project that was the concept, it was ‘each of these are done once’. The idea was for a unique configuration, whereas now I've finished that, so it's just another articulation of that material, I think. I don't see the unique thing here as important as it was.

DL: Would it be true that the distinction would always have been the strongest for you anyway, and then next for the people who played them more than once, and then sort of least for the audience?

JS: For people who heard it once then there's nothing to compare it to of course. Absolutely, so in a sense I was the person who had the best overview of that, clearly.

DL: It sounds fantastic. It's a great combination of sounds and of course Apartment House play it fantastically, and Simon's recorded it very beautifully. Perhaps in the light of the music you've been working on since you stopped the #[unassigned] series, is there a disjunction or even at times a kind of conflict between your interest in procedures and your interest in sounds?

JS: Yes, exactly. I think for the last three or four years – since I started working mostly with instructions and processes, rather than staves, for want of a better way of framing it – I've felt, and I think this is quite a common thing, this split between work which is focused on the beauty of the sound and working with processes. I like creating some sort of aesthetic object which has that sense of craft, where there's something about it which is honed and made into something which hopefully has some beauty to it. And then working with processes where, for me, it's the interaction and the way that those inputs are manipulated and constrained and processed to produce the resulting music, where sound is perhaps just the medium through which that process is articulated. A lot of the pieces I've been doing recently, the sounds – because they're mostly using kind of junk instruments, found sounds, arbitrary categories of sound – they're just there to represent things in the process, and it has a certain characteristic as a result. But I think in those pieces I'm less interested in the specific control of those sounds. It's more the variety and the multiplicity of individual people choosing this enormous range of small sounds which are then combined, and it's that which produces the complexity of the texture. So there's those two extremes really, where the focus is either on the quality of the sound or on the quality of the process, or the interaction between people. One of the reasons for doing this new assigned piece was because I just wanted to explore the beauty of sound again. I'm still oscillating a little bit between those two poles; I think there probably is a middle ground where I make process pieces that have a more specific sonic characteristic, and I think increasingly that's probably where I'll end up going. So rather than saying, you can use any sounds and this is the process, actually specifying what the sounds are and the process as well.

DL: In terms of the context of the music, this piece sits very well with the kind of thing we associate with Another Timbre, but then there are all sorts of connections between this and one of those pieces of yours like everybody do this where performers actually shout instructions at each other, but I would be surprised to see something like that turn up on Another Timbre.

JS: Yes, it's a different aesthetic I think, isn't it?

DL: But there are similar ideas about construction in your older and newer work, aren’t there?

JS: There's certainly consistency in relationships between sounds, but I think that shift is more now towards relationships between people, and that's really become my interest.

DL: Well then that brings us on nicely, because I was going to ask about performers and about virtuosi and non-virtuosi. Even with this piece, given your interest in, say, unstable string sounds, if you had untrained string players, wouldn't they produce even more unstable sounds?

JS: Quite possibly, and I've made versions of #[unassigned] where that was the case. It's the sort of impetus that the score gives to create a certain type of unstable behavior though. I think with the string writing in particular because it's technically difficult to play in places – very high register, very small movements, very controlled – they are very specific things and the results that come from that come from the great skill of the players. But there are other modules I've made where similar results could be achieved with a lower level of skill. I mean, I've played the violin in some of my pieces! And I'm not a bowed string player at all, so I've absolutely no ability there. In those situations I've made things that I can play.

DL: I remember a piece at Colston Hall for clarinet and dictaphones, with Roger Heaton, and that seemed to really dramatise the virtuoso/non-virtuoso contrast because all you had to do is press a button at the right time, and he plays these very difficult things, but it...

JS: It all gets distorted through the network of dictaphones.

DL: And you end up producing these microtonal chords which you couldn't get a group of clarinetists, however virtuosic, to play. But then in assigned #15 it feels like the auxiliary part is doing more some kind of gluing?

JS: Exactly. There was no real sense of foreground in the electronics parts in this recording. And I think that's a general thing that happened over those nine years, that they moved more from being sparse, gestural, pointillist textures, through to these laminar masses.

DL: This is sort of monochromatic. Tim Parkinson talks about single image and multiple image pieces.

JS: Yes, one of the things that perhaps links #[unassigned] with what I'm doing at the moment is that they're single image pieces. I've tended to make one-idea pieces, tried to frame things in a very clear way, so that the clarity of the structure or the process is there, and then the complexity comes from how that process or that structure is articulated, rather than having structures which are difficult to comprehend. So in that sense, I think it is single image, but as soon as you start to recognise things like that, or recognise that process is primary or sound is primary, then immediately my reaction is to try and do the other thing, so there's always an oscillation.

DL: My take on it formally is it sounds to me that for the majority of it it's additive and subtractive, so you have certain textures and you could imagine them coming in a different sequence, and it would give a similar effect – but then towards the end when you get the steady rhythms coming in, and then they don't really resolve, they...

JS: They just kind of drift apart...

DL: They break up... that feels distinct from the way it's been behaving earlier.

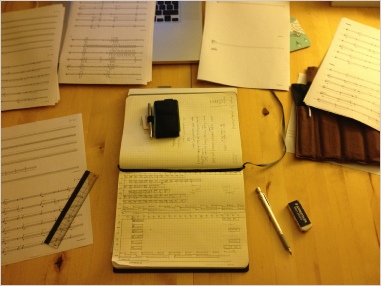

JS: Yes, it does. The way I made the #[unassigned] pieces was to have a grid of squared paper and I put the timings on and the instruments, and then I just draw the blocks to show where everything goes. In the later versions all the blocks are a minute long, so it's quite easy to make in that sense, it's kind of Lego-like, plugging things together. I tend to look for similarities of sound-type, and they drift from one sound-type to another. But there are occasional moments where more coordinated things happen, but on the whole it's that kind of gradual drift, and those sections could be in different orders. It's quite intuitive, there's no method there other than just trying to plan that change of sound over time.

DL: But just the nature of the material, you do get things at some points that create a certain kind of tension which might not be there...

JS: Yes, that's intentional, definitely. But they could be in a different configuration.

DL: Why don't you give the alto flute any low notes? Speaking as a bass player...

JS: Some of it is. A lot of it is low register. There might be some harmonics and overtones that come through. Probably the low tones get subsumed into the general mush of noise.

DL: It's a bit of a facetious question, but I remember hearing in New York Manfred Werder doing a quartet version of his stück 1998, and Manfred was playing his little pitch pipe, and there was very high guitar, and melodica. There's a tendency to do that, it seems, and I think it'd be wonderful to hear that with a tuba and a contrabass clarinet, and there's no reason why not...

JS: With stück 1998 it would because it's octave specific.

DL: But in fact the lower the instrument the bigger the range, in many cases...

JS: Yes, in that case you'd just get a different selection of notes that are unplayable.

DL: But there's something about low pitch having a...

JS: It's probably one of those new music affectations, isn't it? People like high sounds or low sounds. Register has been important for me in #[unassigned], certainly. Extremes are important because once you push instruments towards extreme registers, particularly high register rather than low, their behaviours start to falter a bit. So it's not an interest in ‘high music’ or ‘quiet music’ where pieces exist on boundaries for the sake of it. It's not that sort of affectation, it's because they need to be in that area to get that kind of unstable sound. If you play mezzo forte in the middle of the instrument, it's quite stable, with a good player...

DL: I guess strings can do those subharmonic things...

JS: Of course you can do that, and it's possible. It's often the amount of energy that's put into the instrument and the register. It's a balance between those two. So it's normally one or the other I tended to work with, or both. So if it is mid-register it's likely to have very low energy going into the instrument to create that instability.

DL: Michael Maierhof uses those sorts of sounds, such as string subharmonics, but they do have a very different quality. You could say on paper that they have a lot in common.

JS: He's great.

DL: Yes, I'm a fan... but it does give it a different feeling...

JS: His work I think is a little bit more discrete in terms of sound, whereas those pieces which I made are a bit more blurred.

DL: They're kind of like transparent bits of paper on top of each other.

JS: Yes, exactly.

DL: Anything else you want to say about it, given that this will be the equivalent of liner notes?

JS: The only other thing is that it was lovely to work with Apartment House again, because they made so many of these pieces and knew this material. So without it feeling like some kind of band getting back together, the ten year reunion, it was nice to make a new recording of one of these pieces with people who knew the material. It would have been very different to do it with people that I hadn't worked with before.

Interview conducted in Bristol, May 2015

at88 James Saunders - assigned #15 (2015)

Played by Apartment House

Bridget Carey - viola

Simon Limbrick - percussion

Anton Lukoszevieze - cello

Nancy Ruffer - flute

James Saunders - dictaphones & shortwave radio

Philip Thomas - piano

Kerry Yong - chamber organ

Recorded at the University of Huddersfield, April 2015

Reviews

““I’d like the performance to be as much an expression of the performers’ sense of the music as of mine,” Christian Wolff told fellow composer James Saunders in a 2005 interview. Many conventionally trained musicians surely feel intimidated by that kind of trust and exposure. Others, such as the members of Apartment House, who perform Wolff’s work with notable conviction and success, thrive on that interpretive latitude. Creative imagination as well as intelligence, pleasure in exploration and discovery, inquisitive engagement with a wide range of music conceived in the wake of Cage and (not least) a well developed sense of fun seem to be requirements for such musicians, no less than technical skill and virtuosity.

Saunders’s assigned #15 is part of a series that draws material from his modular composition project #[unassigned]. A bespoke series – to use his word – and this realisation was tailored for a specific occasion, at St Paul’s Hall, Huddersfield in April 2015, and for a particular incarnation of Apartment House. Saunders himself, working with dictaphones and shortwave radio, and Kerry Yong playing chamber organ create a fuzzy glow, bristling with sferics, that hovers around enigmatic wispiness and threshold articulations. Scrapes, scribbles, taps and busy rummaging transmit from Bridget Carey’s viola, Anton Lukoszevieze’s cello, Nancy Ruffer’s flute, Simon Limbrick’s percussion and Philip Thomas’s piano. The result is engrossing: a luminous wash over textured scrawl and discreet graffiti: a Cy Twombly canvas in sound.”

Julian Cowley in The Wire

“This is a weirdly evocative piece. I wrote about James Saunders’s music last year, having heard a CD and attended a live concert of his music. At the time I noted his use of found objects as well as instruments, a focus on process and structure, minimalism, controlled improvisation and group behaviour (cf. The Great Learning). One thing I didn’t discuss at the time was his ability to make pieces from simple gestures using simple domestic objects (coffee cups, sheets of paper) and transcend these materials to make rich, subtle soundscapes far removed from their mundane origins. (I’m trying to remember who made that criticism of musique concrète, that so much of it dwells in the cosy familiarity of the banal.)

Reading Saunders’ own discussion of assigned #15, it all seems straightforward: he had spent the better part of a decade making modular pieces out of combinations of short musical gestures and longer, sustained drones. These modules could be reused, mixed and matched, each piece a one-off. assigned #15 is a new work which combines a selection of these modules into a repeatable piece of music.

The resulting music was completely unexpected. This very rarely happens, but listening to the CD created a very strong sensory impression in my head. The small chamber ensemble, augmented by a small organ, shortwave radio and dictaphones, evoked memories of being on deck for a ferry crossing. The low, constant thrum of the engines, the whistling of a wind that rises and falls, the unsteady rhythms of cables caught in the crosswind, the slow sighing and creaking of the vessel shifting in the water. This is merely my personal affectation but it illustrates the transformative qualities the composition has upon its materials.

The dictaphones distort and blur the other instruments, the radio and organ recede into the wash that simultaneously covers and anchors the other instruments. The strange combination of fleeting gestures and drones means that the music changes from one minute to the next but never loses hold of a unified, enigmatic image. I’ve previously described some of Saunders’ work as verging on technical exercises but this piece goes beyond any technical considerations; it makes a surprisingly bold statement over its unbroken span of 45 minutes.

Much of these qualities are brought out by the excellent playing by Apartment House, assisted by the composer handling the electronic devices. The musicians maintain a relentlessly focussed balance between the heavy and the delicate textures throughout.” Ben Harper at Boring Like a Drill

“James Saunders is another well-established member of the AT family, his previous release on the label having been 2012's Divisions That Could Be Autonomous But That Comprise the Whole. Unlike that album, which consisted of six shorter tracks, assigned #15 just features the 45-minute title composition performed by Apartment House with Saunders himself on Dictaphones and shortwave radio.

This album's title refers back to Saunders' "#[unassigned]" series which he created between 2000 and 2009; they were short fragments for single instruments that could be played and combined in any order to construct a longer modular composition. So, the album of them, #[unassigned] (Confront, 2007) consisted of 131 short tracks lasting about one minute each, 66 for solo cello on one disc and 65 for solo clarinet on another, which the listener was encouraged to sequence using random play, or even to play both discs simultaneously to create a duo. Saunders preferred some of the versions of "#[unassigned]" which he recorded, and these he formalised in his "assigned" series, of which "assigned #15" is an example written for Apartment House, and recorded by them and Saunders on April 16th 2015 at St. Paul's Hall, Huddersfield.

Heard as a piece played by the seven musicians, it seems unlikely one would suspect the modular roots of this composition. Where random playing a series of one-minute recorded modules can lead to clunky jump-cuts between modules, with "assigned #15" that is never the case and it hangs together well, sounding as if it was conceived in its entirety not a chunk at a time. For that, credit is due to Saunders for selecting compatible component parts and integrating them together well, and to Apartment House for their smooth performance of it. The ensemble creates a highly satisfying soundscape that is broad, deep and rich in detail. The piece is engrossing for its full duration and, no many how many times it is heard, it keeps on giving.”

John Eyles at All About Jazz

‘James Saunders spent close to a decade working on his #[unassigned] series. Comprising 175 variations of modular compositions for solo instruments, the project was designed to emphasize unique instrumentation, techniques, and spaces. Repetition was anathema and multiplicity prized—once performed, each arrangement would then be set aside in favor of the next configuration, never to be played again. The UK-based multinational ensemble Apartment House were the first to try an #[unassigned] composition in 2000 and they executed several different versions afterward, until the project was concluded in 2009. With assigned #15, they return to Saunders’s work, now presented as re-performable composition scored for seven musicians who play, among other things, viola, chamber organ, dictaphone, and shortwave radio.

There’s a trace of contradiction in the idea of a once-performed composition. Composing usually entails repetition, regardless of whether variables are introduced to the score. It’s an activity that, either accidentally or purposefully, preserves a number of materials and actions for future use. Even something like John Cage’s Variations II, which requires its interpreter to arrange and measure a series of 11 transparent sheets in almost any way at all, can be repeated, in the sense that different configurations can be saved and attempted again after the first go.

Saunders went a step further with his #[unassigned] works and filed each one away after just a single rendition. What survived between the reshufflings were the constituent parts, the instructions that guided the flute player to sustain a series of long low tones in succession, or that asked the cellist to rub his or her strings without producing a pitch. The series both privileged and minimized the roles of time and structure in music. In one way, #[unassigned] persisted as an asterism of instructions, in another it survived because those instructions were intermittently organized so that a group could recognize and perform them in relationship to one another.

With assigned #15, Saunders exhumed an old #[unassigned] variant and recorded it with Apartment House at St. Paul’s Hall in the West Yorkshire town of Huddersfield. In an interview on the Another Timbre website, James says that he returned to this material because he wanted “explore the beauty of sound again,” versus focusing on the processes that produce such sound. assigned #15, then, is music frozen into a particular shape.

It’s a decent image for what the album sounds like: a dense, opaque block of ice shaking under internal pressures. A constant machine-like drone rumbles throughout the piece, its source not easy to determine. It could come from the chamber organ, but it might be the product of the dictaphones and shortwave radio too. Similarly, some of the tapping, rhythmic sounds could be traced back to string instruments or they could as easily belong to the percussion section.

Bowed metal, quickly struck piano keys, scratch tones, rattling chains, and piercing train-whistle whines also find a place in the music. They move in and around each other with such ease that it’s hard to find where one section ends and the next begins, and that contributes to the performance’s heaviness. All of the softer sounds, like the fragile string and flute interaction in the album’s second half, congeal with the rougher-edged, glass-on-sandpaper textures, forming a tight grid of noise that never loosens, even as the work winds down and the chamber organ hums in relative isolation. The piece changes over time, but it never seems to move forward. Instead, it spins in place, or spins and simultaneously revolves. Different facets reflect off its surface as it moves through different positions, but its insides are always hidden. The music may be frozen in its course now, but the sound travels forward anyway, with or without the composer’s dispensation.

Lucas Schleicher at Brainwashed

“Composer James Saunders' piece, titled "Assigned #15", is performed here by the ensemble Apartment House, of which Saunders is also a member. Presented as classical music, the swampy, uneasy soundscape on this disk is as brooding, haunted and unsettling as any ominous 80's industrial recording.

It is a mixture of sparse, antimusical use of orchestral timbres, heavy room noise and muffled ambient effects. Like Ligeti or Schoenberg, the emphasis is placed on the brightly gleaming treble ranges of the horns and strings, and the gradations of anxiety within their most dissonant intervals. The numerous wind players rarely join in unison, sounding out forlorn tones individually which bend downward in sickly despair as they end.

This chaotic, arrythmic mass of uncomfortably clashing tones is a 'composition' in the tradition of John Cage and other writers of highly specific instructions which seem to produce nearly arbitrary results. The sheer randomness of the players' activity creates an eerie emotional detachedness.

A sort of lonely, windy howl underlies the scattered activity at most points, drawing the chaos together into a continuity of drone. The saturated and insistent whine of shortwave radio static (Saunders' instrument of choice) builds up over time, and overtakes the mix gradually, a persistent electric hum of vitality. The texture of the drone is sour, detuned and far from meditative or reassuring, reminding me of the surreal and nonsensical thoughts which creep into consciousness just before sleep.

In this regard, it describes accurately a sensitive, visionary state of thinking, as coldly offputting as it initially seems. This darkly glittering gem of an album could be filed comfortably next to John Zorn's "Absinthe" and Nurse WIth Wound's "Soliloquy for Lilith". It possesses the rare luminous blackness of artists such as Coil and Cyclobe, here achieved through acoustic means. It is magickally charged space.”

Roger Batty, Musique Machine

Discount price £5