Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

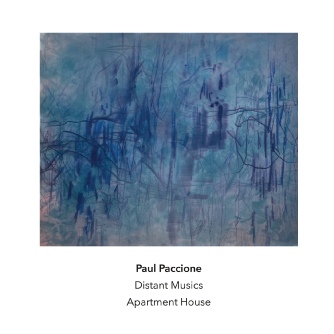

Paul Paccione

Artworks below by

Anton Lukoszevieze, with thanks

at224 Paul Paccione ‘Distant Musics’

Five chamber works from the 1980’s and 1990’s, played by Apartment House

1 Exit Music (1983) 16:20

Mira Benjamin, violin Bridget Carey, viola Anton Lukoszevieze, cello

2 Gridwork (1980) 7:30

Heather Roche, clarinet Raymond Brien, bass clarinet Mira Benjamin, violin

Anton Lukoszevieze, cello Ben Smith, piano

3 Violin (1980/rev.1987/2022) 20:07

Mira Benjamin, Chihiro Ono, Amalia Young & Angharad Davies, violins

4 Distant Music (1990/1991) 13:41

Heather Roche & Raymond Brien, clarinets Mira Benjamin, violin Bridget Carey, viola Anton Lukoszevieze, cello

5 Still Life (1983/rev.2013) 11:00

Nancy Ruffer & Emma Williams, flutes

Interview with Paul Paccione

Tell us about your background and how and when you came to experimental music?

I was born in 1952 in New York, and raised in Brooklyn. Like many baby boomers, my earliest musical experiences were playing electric guitar in neighborhood rock and roll garage bands. We played cover versions of the latest music we heard on the local rock radio stations. I learned most of this music by rote - listening repeatedly to successive fragments of a recording until I was able to accurately replicate them on the guitar. This was my first attempt at getting inside a piece of music.

My formal musical training was primarily in and around colleges and universities. I began formal music study at the Mannes College of Music (B.M., 1973) in New York City, with a major in classical guitar. Mannes’s curriculum was modeled on that of a traditional European music conservatory. It was completely different from my previous informal music training and was a totally new world for me.

My first-year music theory teacher, Eric Richards, was a composer. He remained a mentor, close friend and colleague of mine until his death in 2020. Eric was an extraordinary teacher and he turned that class into something much more than the usual general introduction to the prescribed rules of harmony. He introduced me to the world of avant-garde music. His teaching and guidance, as well as his own visionary compositions and compositional thought, exposed me to a vast new musical landscape. He opened up a whole new world of sound and forms of expression that inspired me to begin composing.

Subsequently, I changed my focus from classical guitar to music theory. The two music theory subjects that were of particular interest to me at Mannes were Species Counterpoint and Schenker Analysis. I continue to be influenced compositionally by the attention each brings to bear on voice-leading and the ways in which the musical surface is related to its skeletal underpinnings.

On Richards’s recommendation I began private composition studies, outside of Mannes, with composer/visual artist Harley Gaber. I was his only student. These lessons continued for several years. From him I learned to examine, critique and ultimately trust in my own intuitions. He reflected in his teaching a keen knowledge of modern art and had the unique ability to articulate both musical and notational concerns/possibilities in terms of another medium. At this time, he was just beginning to compose what he described as “slowed down music.” When he died in 2011, he was recognized as one of the early pioneers of minimalist drone and spectral music.

My early student compositions were strongly influenced by the freely atonal compositions (Opus 5-12) of Anton Webern. As a point of entry into his music, I sometimes copied the scores from these works by hand, closely examining the individual aspects of the music (phrasing, dynamics, articulation) and, in particular, their cell-like/organic construction wherein everything was attributable to some form of developing variation. I was also influenced by the music of Morton Feldman, in particular his compositions “Durations I-V” and “Between Categories.” What I most admired was his meticulous sense of instrumentation in conjunction with exact registral pitch placement. What interested me, in particular, was Feldman’s attempt in these works to bridge the gap between stasis and movement, as well as determinate and indeterminate methods and outcomes in music.

In addition to my music studies, New York City itself was an important part of my education. I immersed myself in everything the city had to offer (museum exhibits, theatre, art-house movies and concert performances). It was a fertile period for the production and performance of contemporary music and modern music was an important part of the city’s artistic culture. Pierre Boulez was the recently appointed music director of the New York Philharmonic and he regularly programmed twentieth-century music. Elsewhere in the city one could find regular performances of the music of John Cage and Morton Feldman, as well as other American experimental composers. In Soho, the music of the emerging minimalist composers was first being presented. Around the corner from Carnegie Hall, the most recently published new music scores of Berio, Bussotti, Boulez, Cage and Feldman were readily available for browsing and purchase at Patelson Music House. By way of Harley’s organizing and presenting new music concerts at the Museum of Modern Art and other venues, I came in contact with a diverse community of performers and composers – a community of artists that I hoped to one day become part of.

Upon graduating from Mannes, I began graduate studies in music composition and theory at the University of California, San Diego (M.A., 1977) to study composition with Harley’s former composition teacher, composer Kenneth Gaburo. When Gaburo unexpectedly made the decision to extricate himself from the university in order to devote his energies to his music publishing business, Lingua Press, I continued my composition studies with him at his home in La Jolla, often in exchange for assisting him in various tasks related to the press (for example, music copying).

My composition studies with Gaburo focused primarily on the numerous potentials in musical text setting (what he referred to as “compositional linguistics”) - this would begin for me a continued engagement with vocal music. Unlike my lessons with Harley, whose approach to music was almost Zen-like, everything (life and music) was a form of confrontational theatre for Kenneth that involved an unrelenting questioning of musical assumptions. In this sense, every lesson was a process of musical, as well as personal, discovery. (Reading list included Jerzy Grotowski’s “Towards A Poor Theatre,” Peter Brooks’s “The Empty Space” and Jacques Maritain’s “Creative Intuition in Art and Poetry.”)

U.C.S.D. was a center for American experimental music and it has remained so. The composition faculty was made up of composers whose music, compositional aesthetics, and approach covered a wide range. They included Kenneth Gaburo, Roger Reynolds, Pauline Oliveros, Robert Erikson, Robert Shallenberg, Bernard Rands and Wilbur Ogdon (with whom I wrote my thesis on selected English language text settings of Igor Stravinsky). The music of my fellow student composers and performers covered an equally wide range of interests and backgrounds. The overriding purpose was for all performers and composers (faculty and students) to explore (experiment) and discover new means/forms/avenues of collaboration and making music together. While at U.C.S.D. I met my future wife, clarinetist Molly Lash - beginning what continues to be a highly productive and collaborative working relationship in music.

I later studied composition with composer/conductor/violist William Hibbard, at the University of Iowa (PhD, 1983). I first came in contact with Hibbard’s music when it was published in Lingua Press and admired the music’s clarity, transparency and rigor. Hibbard was conductor of the Center for New Music – an independently financed group of professional musicians who were dedicated to performing contemporary music on a regular schedule. Both my wife and I became closely associated with the Center, she as resident clarinetist and myself as assistant to the conductor. As a conductor, Bill knew exactly what musical elements and factors of a piece required the conductor’s attention, as well as the most efficient means of communicating to the performers the composer’s intentions.

I came to Iowa with a backlog of compositional ideas on the direction I wanted my music to take. It was by way of Hibbard’s openness to and encouragement of these ideas, as well as his leadership at the Center and his impeccable ear for pitch relationships and orchestration, that I realized my ideas and found my own compositional voice.

So have you always earned a living from music, or did you have to work doing something else?

To be influenced is to be taught and this was especially the case of my own musical life and career. All of my composition teachers imparted to me a sense of something being left unfinished and open to further exploration. I cannot overstate the important role my teachers had in my musical development and this is the main reason I hoped to devote much of my professional life to teaching.

I joined the faculty at Western Illinois University in 1984 and I retired in 2018. The relationship between my teaching and music was reciprocal - one informed the other. I taught a wide range of undergraduate and graduate music theory/composition courses (chromaticism, orchestration, counterpoint, composition, analysis, 20th/21st - century compositional techniques and American music). It was by way of communicating my ideas on these topics to others that I was able to clarify my own thoughts and sharpen my skills.

The University community provided me with the opportunity to establish productive and collaborative relationships with a wide range of performers, conductors, and ensembles who were dedicated to performing my music. As a result, the majority of my compositions are written with specific musicians in mind. In regard to musical style and language, this has resulted in a diverse body of music for an equally diverse range of instrumental combinations and musical genres (chamber music, large ensemble, opera). However, in spite of the diversity, the same compositional perspective and considerations are always present in my mind. In addition to teaching, I was codirector/cofounder of the department’s annual New Music Festival, through which a large and diverse number of national/international composers and performers visited the campus, over the course of 31 years, to share their music.

Can you tell us about the pieces on the CD? Who were they originally written for, and how often have they been performed? Were you part of a circle of like-minded musicians, or were you largely working in isolation when you composed these? How does it feel coming back to pieces that you wrote about 40 years ago?

I composed seven works during the three years I was at Iowa – all of which received their first performances by the Center and were subsequently performed, by others, at various festivals in different settings. Four of these compositions appear on this recording. It is the first time they have been made widely available on compact disc as one unified entity.

The music presented on this recording is contemplative in nature. Individual moments tend to become absorbed into the overall presence or aura of the music. Each individual composition bears a trace of what has preceded it and each individual composition holds itself open to works that will follow it. In this sense, there are no clearly defined boundaries between pieces but there exists between the works a system of intertextual relationships.

In all of these works my compositional means is one of distillation and intensification – focusing on what is inside the sound without sacrificing the music’s overall sense of harmonic motion. I try to get to the essence of the musical expression with each piece through both intuition and recognition of what is irreducible in the music – an orientation to the material itself. In each piece my desire is to create one uninterrupted musical continuity, with each successive sound evoking sensations of the same order and of the same purity as the first sound.

My goal is to strike a balance between: the horizontal (linear) and vertical (harmonic) dimensions of music; between pitch (that which is measured) and sonority (orchestration); and between structure (the network of relationships) and atmosphere (that place in which the work exists – its sense of place).

When I retired from teaching, it was my plan to quietly reflect on my past compositional work, continue to compose new music, and pursue performances and recordings of my music.

For me, returning to pieces I composed forty years ago is not unlike reencountering a dear old friend from the past, whom you haven’t seen for many years but have a deep connection, and with little or no effort picking up on things exactly where you left them a long time ago. I am particularly grateful to Anton Lukoszevieze and all of the performers in Apartment House for providing me the rare opportunity to do so.