Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

at46 no islands John Cage’s Four6 + 2 improvisations

Stephen Cornford amplified piano

Patrick Farmer turntable & electronics

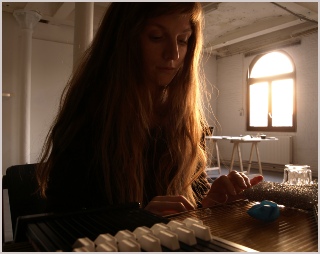

Sarah Hughes chorded zither

Kostis Kilymis electronics

1 Improvisation #1 09:21 youtube extract

2 Improvisation #2 17:10

3 John Cage Four6 30:10 youtube extract

Total time: 56:41

Recorded at Oxford Brookes University, March 2011

Interview with Sarah Hughes

“The relation to listening, improvising and

structure is very intriguing in Four6 and

I find the framing quite impish.”

Firstly could you explain how you came to this kind of music? Are you musically trained, and how would you describe your current engagement with music and art?

I initially found this kind of music by trial and error, I wasn't satisfied by what I was listening to, but didn’t really know where to look, or what I was looking for. I bought the Looper Squarehorse disc shortly after its release in 2004 and that interested me quite a lot, and some documentation of an installation Alfredo Costa Monteiro had done in Barcelona directed me towards his music. I think I just looked until I found things I liked and was sometimes rewarded with something great, and inevitable one finds links and names though names and eventually I could filter out more and more to find the stuff I was interested in. In 2007 I met Patrick (Farmer), and he was already quite involved with a lot of musicians and was promoting this kind of music, he played me Wolff's Stones shortly after we met and I was really happy; it’s a recording that certainly holds a lot of significance for me in terms of composition, space and material. Around this time I was also reading a lot of David Dunn and the two seemed to relate a lot to what I was doing with installation, there is definitely a reciprocity between my installation and performance and drawing and listening, if in a more cognitive sense. Externally I think the two, music and art, have remained quite autonomous, perhaps because I find sound a difficult material to work with, but in terms of space and compositional intrigue the two are part of the same practice.

I was taught violin when I was younger and have retained some music theory, and can read music, but I was taught to pass exams and found it a rather detached way of learning and stopped at grade six when I was around 13 (with some regret) and took up guitar, which I still play now. I was given the zither a few years ago, and didn't really know what to do with it for a while, I'm still working it out.

When I've seen you perform, you mostly play very quietly and with frequent long pauses. These are both qualities often associated with Cage's late music, but in the recording of Four6 on 'No Islands', you are actually really busy - and the music as a whole is really beautiful but has a quality of wildness. How did you approach the score, and was it challenging to perform?

The relation to listening, improvising and structure is very intriguing in Four6 and I find the framing quite impish, in knowing that the other performers have set brackets for set sounds, and thus a somewhat limited response to your own sounds does give it, as you say, a quality of wildness, but at the same time, there is a massive opportunity to listen and a sensitivity to what, in that moment, one can hear. I first played this score in Brussels with Patrick, Kostis and Julia Eckhardt, and I approached it in a similar way to my usual manner of playing little and quietly and I restricted the times at which I could play to a very limited period. The value of this score is the freedom to make those decisions, and in the recordings with Stephen, Patrick and Kostis on “No Islands” I wanted to try it differently, and felt it much more successful as it freed up the listening and the improvisation elements. I also wanted to make some noise, I like making noise occasionally, and am not a particularly confident performer, so the brackets seemed to allow for a bit of recklessness on my part. The challenge of the score is knowing it, and in knowing becoming more malleable, your description of beautiful and wild is I think a testament to that.

“For me the notion of external sound is at the forefront of this realisation.”

The recording of Four6 is also striking because of the wholehearted way in which you embraced chance as a constitutive element in the music. In addition to the chance-derived structure of the piece, your realisation introduced other chance elements that I

think add to both the interest and quality of wildness. Can you tell us about this?

The drama studio at Oxford Brookes, where the album was recorded is set between Headington Hill park and some allotments, so the spring birds were apparent to us as absent figures throughout the recording, as was the frequent passing of light aircraft and the occasional passer-by. Before recording the Cage piece we opened the double doors of the drama studio, which back on to the allotments, and so added an extra dimension to the realisation, a spatial quality which opened out the recording. For me the notion of external sound is at the forefront of this realisation, as each player can be considered autonomous, or not, and the external, environmental sound can to be considered as situational cues, or not, it toys with the varying levels of the reception of sound, and the value given to each, and its perceived quality. It becomes an aesthetic response to an acoustic environment, the brackets allow for this, and the score as a whole frames a period of attention. I think Michael Pisaro’s Only [Harmony Series #17] works in a similar fashion, when he asks of it "What, in the sum of things occurring now, do I hear, and how do these things harmonize themselves?” Of Four6 one could ask - "how do these things relate to one another?", which could be disjunctive, and often is.

I believe you first played with Kostis Kilymis at the residency you mentioned at Q02 in Brussels. Can you tell us a bit about that residency, about how it worked and how it affected you musically?

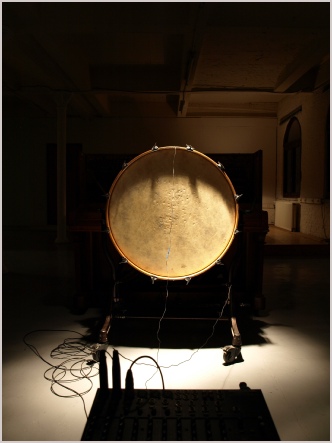

Patrick and I spent two weeks at Q02 in March, with Kostis joining us for the final four days and then returning to Oxford with us to record. Q02 is a wonderful space, and really affords a lot of opportunity for experimentation. Julia and Ann are very accommodating, and open, and honest, which is a fabulous combination. For the first week Patrick and I worked on a duo that he'd written for zither, piano, bass drum and feedback, I also took the time to do some drawings, and Patrick some recording. When Kostis arrived we spent the time on Michael Pisaro's A discrete reconciliation

between balance and flux, which he'd written for the residency and we also played a lot of improvisations. It was great introducing Kostis to the residency as Patrick and I know each others playing rather well and it was good to have someone we were both quite unfamiliar to change the dynamic. We went to Q02 with the intention of allowing the situation to dictate what we did, the space became integral to the residency for us, an instrument in many cases, such as the duo and the Pisaro score and the improvisations tended towards a bricolage of found material, forks and glasses, paper, postcards from around the space. The residency lends itself to a mode of working that is very site responsive, the degree to which was made apparent when recording the same pieces, four6 and A discrete reconciliation between balance and flux in the Drama Studio the day after we returned from Brussels. Spending the time at Q02 before hand undoubtedly informed our realisation, both in my wanting to move away from a sparse realisation, and also in the site responsiveness, which is why it seems so fitting to have the bird song so apparent in four6. This is also the reason the Pisaro score was unsuccessful in this instance. The instrumentation, which we had kept the same in Brussels and Oxford, didn't respond so well and the score was somewhat deadened in the Drama Studio, and the environmental sound became an intrusion, the richness of the acoustic in Brussels was central to how we'd chosen to realise it. This is an element of recording and playing, and field recording, that I find relates very strongly to how I approach installation and drawing, in how one articulates a space as a material, and how the volume of a vacancy can inform, and is integral to a piece. The performative

silence in composition and improvisation is paralleled, for me, by the exhibition space of an installation, the space that allows one to recognise the relation between objects and their material quality. In Brussels I tended to act as a mediator between Patrick's and Kostis' playing, so when we were joined by Stephen on our return to Oxford the dynamic inevitably changed again, with the various degrees of familiarity making apparent the quality of each of us, dependent on the quality of each other, dependent on the quality of the room.

“I see a lot of similarities in reading Lucretius and improvisation, and in something like making good coffee.”

The qualities or practices that you describe in the playing situation - such as mediating between different musical personalities or responding to/using the particularities of the room etc - have in a way been staples of improvised music since the 1960's, though I feel that a number of younger players like yourself are currently giving them a new twist. But I'd be interested to know if you feel yourself as being part of that now rather long tradition of improvised music? Is it something that you are conscious of - whether positively or negatively - in your practice?

I’m certainly conscious of the context in which I play, and the context in which I make work, I think that its integral to how I approach what I do, though I’m more aware of the visual art context than the music side of things, I certainly know more about the arts, but they parallel each other a lot of the time, and in my mind are often interchangeable. Do I feel myself part of that tradition? In many respects I do, the artists and musicians that I've met though Compost and Height and through playing appear indicative of a certain zeitgeist with which I feel an association and with which I share a common approach. The recurrent discussions around this music, on and off line, are indicative of the general awareness and respect that people involved in this sort of music have for one another and for the music being made, and that is continuing to be listened to. I think unless there is an attempt at replication, being aware of the context in which one is working, both historical and contemporary, can only be a positive thing, as is extending that context as far as one can, which is also something i find prevalent in this sort of music, and something Wolf Notes attempts to respond to. I see a lot of similarities in reading Lucretius and improvisation, for example, and in something like making good coffee - how the physical characteristics of a substance affects another, that’s everywhere, all the time - its an obvious correlation, but one which continues to intrigue me.

Reviews

“As purveyors of the Compost and Height website/label and untiring makers of things, Patrick Farmer and Sarah Hughes have high profiles of late, and this little disc won't do anything to diminish that. With Farmer on turntables and electronics, Hughes playing chorded zither, Kilymis on electronics and Cornford with his amplified piano, this quartet tackles John Cage's "four6" and a pair of short improvisations. Their usual stock in trade is a mostly quiet carpet of crackle, hum and fizz, often mimicking natural sounds, as in the first few minutes of the first untitled improvisation which sound much like rain on a flat surface. Squeaking and ominous rumbling then accumulate and threaten to get out of control. There's a definite feeling of chaos just beyond, as hums grow and divide and electric pops intrude, which are peeled away to reveal a skipping, skittering plasticity with an electronic pulse with odd bell-like sounds. It's often difficult to imagine how these sounds are being made, and that's half the fun.

The second improvisation has an odd metallic cloud hanging in it, and a wall of squeak and wail gives way to a quiet chord with low bass hum and delicate feedback. Way underneath I can hear birds. The changes then come a bit too quickly to describe in detail. There's an awful lot going on and things happen very quickly. Textures appear, shift and rub against each other in a myriad of ways. Sonic surprises and an occasional LOUD crash or bang keep the attention from wandering.

Lastly they work with one of John Cage's "number pieces". These late compositions were all written in a similar way, with timed brackets indicating when and for how long a sound is to be played. Each player gets to choose what sounds they will be using and where they will enter and exit within their allotted times. There is usually a time limit to these pieces, and many players have chosen to present them as loops, repeating the structure a set number of times. I believe that is what's happening here as well, as events seem to repeat over time, but shift slightly in relation to each other. Overall, this piece is a bit more subdued, with events following one after another over a bed of birdsong and occasional quiet voices. Spare piano notes hover and turn into quiet feedback, crackles like fire arise and dissipate, and odd metal brushings hang about in the corners. On headphones this is a feast of detail. No wonder it's made so many people's 2011 'best of' lists.”

Jeph Jerman, Squid’s Ear

“This disc captures well, I think, something I really enjoy in the playing of Farmer, Hughes and Cornford, certainly – I'm not really familiar with Kilymis' playing, though Organized Music from Thessaloniki is indeed a fine enterprise – which is the balance between an almost tentative stillness and quietness (the potential, at least, for that to be there) and an almost visceral wildness – as when, on the first improvisation, a sudden blart of feedback rudely blares out like a mistake, is ignored, and doesn't recur; or the fact that, at the end of that improvisation, everyone else's gentle electronic ebbings away are overlaid with Farmer's loud and physical and tactile turntable-surface frictions. It's an aesthetic a million miles away from capital n Noise Music – though bits are noisy, and many of the sounds produced would be considered 'noises' by most 'straight' listeners – but it's not in the least prissy or monastic in its restraint, delighting in the rasps and whirrs and burrs of its ugly beauties before settling into a kind of contemplative ambience in which the distant, twittering frequencies of birds or passing planes act as spectral, barely-registered presences, sitting there waiting for the musicians to stop dropping things on zithers or making whooshing noises with electronics or manipulating the insides of pianos. Maybe that's partly a quality of the room itself – I've seen Farmer and Hughes, this time as part of the Set Ensemble, with Bruno Guastalla and David Stent, perform a different version of the Cage piece which makes up half of 'No Islands', once in rehearsal, with the door open on a balmy spring afternoon, and once again in the evening, where a different focus or tension (and the presence of audience) was brought to bear on proceedings. In both cases, though, the room – a square black box, quite tall in relation to its width – seems to inspire a kind of openness, a relaxed focus, perfect to the simultaneous focused activity of both Four6 and improvised music: set away from the main body of the Oxford Brookes campus, on the side of a hill, above allotments and trees, inside it feels as if one could create a safe and sequestred world of focussed experiment, and yet at the same time feel open to what occurred outside, in entirely un-cloistered freshness. I guess this information is anecdotal, but, after all, Keith Rowe is always stressing the importance of the room, or space, in which one performs, and it's that combination, of person and environment, that allows music like this to breathe. As too you should listen to it in a space where you can breathe, to let the many wonderful things here soak in – for there's a delicious and perverse richness at times, as when (this on the

second improvisation) a generally sober drone is packed over with all sorts of strange and wonderful little interventions: a rumbling stomach imitation; someone (Farmer no doubt) emptying something out of a bag; a whoop-wailing theremin-like sound which actually made me laugh out loud on first hearing, at its voice-likeness, its incongruity, its near-parodic yet curiously touching emotional tint. 'Four6' is the quietest thing on here, though the door to the studio is now open and the birds outside are in full and frequent voice; and maybe I prefer the (relatively) wilder territory of the improvisations, but, as the disc rides out on those continuing birds, a piano-belltoll, a siren (outside intervention), a bowed zither zing, a turntable scrunch, another piano strum, and a fade-out, all this making its way into the otherwise silent living room here at 1AM, I'll take the Cage piece too. This is, as they (who?) might say, a sweet record. “

David Grundy, eartrip magazine

“Maybe it's because I'm writing this at the tail end of two weeks + of constant concert going and my music-listening brain is a bit frazzled, but it's difficult for me to figure out what to write about this release, other than to say I like it a lot. The quartet (electronics, turntables, chorded zither and amplified piano) occupy the kind of quiet-yet-scurrying territory that's not so uncommon but do so exceptionally well, breathing air and vitality into an area that often gets overcrowded. They perform two improvisations and then Cage's "four6", the latter in a bird-heavy environment and beautifully paced. The entire recording bristles with intelligence and care--I'll leave it at that. An excellent job--listen.”

Brian Olewnick, Just Outside

“Dernière publication de cette série consacrée à la postérité de John Cage et de Wandelweiser, No Islands réunit quatre musiciens pour deux improvisations et une pièce de John Cage justement, Four6. Certains des musiciens sont déjà présents sur Droplets, Patrick Farmer aux platines et à l'électronique et Sarah Hughes à la cithare préparée, auxquels s'ajoutent Stephen Cornford au piano amplifié et Kostis Kilymis à l'électronique.

Parlons tout d'abord des deux premières pièces improvisées. Il ne s'agit plus vraiment de l'univers des précédents disques (Droplets, Caisson et Division that could be autonomous but that comprise the whole) très marqués par le réductionnisme et le collectif Wandelweiser. Nous nous retrouvons plutôt face à des improvisations électroacoustiques plus corrosives, marquées par des fréquences électroniques sinusoïdales et/ou ultra-aigues, une absence de silence, malgré des pauses fréquentes des musiciens pris individuellement. Peut-être plus agressif et industriel aussi, le quartet explore des textures sonores froides et métalliques, utilise des mécanismes et des imperfections électriques. Mais la même quiétude et la même sérénité semblent omniprésentes tout au long de cette vingtaine de minutes d'échanges interactifs et de superpositions de strates texturales originales. Le même calme oui, mais avec beaucoup plus de reliefs, de jeux sur le volume et l'intensité, sur les différents timbres et leur opposition tout comme leur point de rencontre où chaque son renforce l'autre, le déploie et l'exacerbe. Car l'écoute entre les quatre musiciens est toujours très attentive, la concentration paraît souvent à son paroxysme et une place est toujours accordée à chacun, à son intervention autant qu'à son absence de production sonore. Une musique très équilibrée en somme, exempte de tensions mais riche de sonorités et de dynamiques variées.

La troisième pièce, Four6,est une partition pour quatre instrumentistes composée par John Cage en 1992, peu de temps avant sa mort. Comme dans la plupart des œuvres tardives du compositeur américain, le hasard ainsi que le « silence » (je le mets entre guillemets car je ne crois pas que Cage s’intéressait réellement au silence à ce moment, j’y reviendrai) prennent une place prépondérante et acquièrent de plus en plus de consistance. Pour cette pièce, Cage s’est contenté d’écrire quatre partitions qui délimitent et divisent chacune trente minutes en douze unités de temps différentes. Pas d’autre indication harmonique, instrumentale ou rythmique, c’est à l’interprète de choisir l’élément sonore qu’il produira durant chacune des douze périodes, une liberté complète est laissée au choix de l’instrument/objet, de l’intensité, de la valeur, etc. La restriction est minimale, et les potentialités qui s’ouvrent touchent à l’infini ; dès lors, on comprend aisément pourquoi cette pièce a tant été jouée par des artistes issus de la musique improvisée. Concernant cette interprétation, la première originalité à noter est l’utilisation surabondante des sons extérieurs : le quartet joue toutes portes ouvertes et laissent les chants d’oiseaux comme les bruits d’avion pénétrer et habiter le lieu d’enregistrement. Je reviens donc sur ce fameux silence, car si le choix d’exploiter l’environnement extérieur m’a paru tellement judicieux et intelligent, c’est dans la mesure où John Cage, à mon avis, s’intéressait bien plus à ce qui pouvait survenir lorsque la musique cessait (nous retournons donc sur le terrain du hasard et de l’aléatoire en fait), bien plus qu’au silence en tant que matériau sonore exploitable en tant que tel, comme pourraient l’utiliser Malfatti ou Pisaro par exemple. A l’intérieur de ce cadre structurel se déploient donc des sons calmes et sereins toujours, moins agressifs que lors des précédentes improvisations, mais aussi plus éparpillés. Les interactions ont du mal à se faire mais lorsque les divisions temporelles le permettent, les dynamiques de chacun se rejoignent et s’assemblent en des points synergiques qui épaississent considérablement l’intensité de la pièce. Une pièce toute en tension, marquée par le hasard et l’attente, la volonté et la contrainte, la nature et la création artistique, cette réalisation de Four6 donne constamment l’impression que les quatre musiciens cherchent à se rejoindre à travers les dédales d’un labyrinthe qu’ils s’approprient progressivement.

Trois pièces qui brouillent les frontières entre la musique écrite et la musique improvisée, faites de tensions et de dynamiques variées. Le timbre est pleinement exploité et travaillé, et les interactions entre chacun des musiciens se déploient à l’intérieur d’un univers plutôt original, entre improvisation électroacoustique, post-réductionnisme et musique aléatoire. Un univers très méditatif, beau et plutôt calme au-delà des emportements corrosifs et industriels surtout présents dans les improvisations.”

Julien Heraud, Improv-Sphere

“According to someone’s opinion, it is better watching non-idiomatic improvisers at work during a live performance in order to have a clear idea of what they’re concocting and gain a deeper understanding of what they put in a recording to be enjoyed at home. Your chronicler stands at the opposite edge, preferring a “semi-blindfold” approach while a disc spins, trying to vaguely guess the origins of certain sounds by having a quick look at the palette or doing nothing at all, letting the acoustic secretions take me by the hand and lead the dance without chronic coughers and ear-whispering nerds around.

Naturally the results must be interesting enough, possibly suggestive. According to that logic No Islands (whose instrumentation includes turntables, electronics, chorded zither and amplified piano) is a fine achievement reiterating itself upon additional sessions. Consisting of two improvisations and a version of John Cage’s “Four6”, the record is endowed with a general sense of well-placement of its constituents, transmitting an almost ideal balance of organic, startling and transfixing traits. The timbral contrasts are cleverly exploited to create moderate hostilities destined to inevitable peace; broad-spectrum processes that nearly give the impression of being premeditated, yet without the “been-there-already” atmosphere typical of numerous recordings in this field. One feels that everything is under control at any time, surging hums, regulated feedbacks and vociferous rummaging in overall concord below the incivility level.

The contributors are perceived as vigilant witnesses of the music’s unfolding, followers of currents self-generating from the very sources. The birds, the children’s voices, the distant planes and the urban echoes heard throughout Cage’s piece seem to belong from the beginning, globules of awareness amidst splashes of untreated colours, no compulsory gestures and acts in sight.”

Massimo Ricci, Touching Extremes

“Patrick Farmer and Sarah Hughes reappear on No Islands, this time in a quartet with Kostis Kilymis on electronics and Stephen Cornford on amplified piano. The four play two improvisations and a version of Cage's "Four6"; despite the prevailing Cageian ethic of this set of releases, this is the only actual Cage composition on any of the albums. This version of "Four6" is the second released by Another Timbre, the first, by Tom Chant, Angharad Davies, Dominic Drew and John Edwards, having appeared in 2009 on the fine Decentred. (The label has also released an album of Cage's "Four4," further evidence of Reynell's steadfast adherence to his initial intentions throughout Another Timbre's four years.)

Comparisons between the two versions of "Four6" highlight the flexibility of Cage's composition in which, "The performers choose twelve different sounds each, with fixed amplitude, overtone structure etc., and play within the flexible time brackets." Those time brackets ensure that the players do not get in each other's way and serve to give the composition the open feel of a good improvised piece. The performers' choices of sounds shape the end result significantly. This version opens with birdsong—selected by one of the players, not ambient—and it recurs throughout the half-hour piece as a signature motif, alongside swelling bowed notes, percussive rattlings and thumps, electronic tones and drones, and struck piano notes. The recording is exquisite, allowing—as it should—the beginning, middle and end of each sound to be clearly heard and savored. As a version of "Four6," it is first rate, illustrating its beauty and ingenuity.

In the main, the two improvisations achieve a good four-way balance between the players, as overlapping sounds come and go in a manner similar to that of the Cage piece. However, the improvisations contrast with the composition in that they lack its structure and balance between the four players. So, occasionally the electronics or percussion can play too loudly or for just too long, dominating the quieter instruments. This is particularly true of a booming low frequency electronic drone which sometimes drowns out other sounds. This is not a major problem, but it does serve to highlight the advantage for an ensemble of playing a composed piece if the instrumental sounds do not have comparable dynamics.”

John Eyles, All About Jazz

“The packaging is lovely on this release(kudos to Sarah.)

This will not be a critical review but observations.

I very much enjoyed listening to this recording but it probably would have been even more so if I had been

in the room during the performance because….

1. There is a lot of space in between sounds.

2. To see how these sounds were performed would also be interesting.

This music to me seems to deal only with timbre & form/structure.

This is not a problem for me but if your expectations are otherwise you might be waiting for something to happen.

A question this music raises for me is

What is the function of this type of sound activity from a listeners point of view

and should perhaps this be more specifically called “sound art.”

When I speak of “function” from a listeners point of view

what I mean is: As a recording-when do you listen to this & why?

For me, I like to listen to this type of music as I go to sleep

“Sleepy-Time Music.”

Lately have been listening to John Cage text pieces

(empty words, re: Morris Graves etc)

for that purpose.

I would not hesitate to recommend this recording but

another question it brings to my mind is-

Are these typical sound gestures from the parties involved?

meaning- Are these improvisations typical of their work?

I am not familiar with these persons work so I cannot say.

In my experience, people have preferences and Cage is

usually about avoiding personal preferences.

A funny coincidence is that I was at the premier of Four6

in New York but I think I left before it was performed

because I was impatient & the planes over head

were distracting me(that would not be a problem now.)

One last question, as to function of recorded music of this type,

Because of its quiet dynamic range the ambient sound of my home

tends to overtake this music.

That being the case–Why not just listen to the street sounds

of San Francisco?

On a personal taste issue, I think I like things a little Juicier.

Not a criticism I just like to feel the sounds a little more.

Excellent work by all parties involved & I would

like to hear another realization of Four6 as well as

anything else this group has to offer.”

Gordon Knauer, The Watchful Ear

Discount price £5