Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

Booklet for John Cage Number Pieces Box Set

disc two

1 Five (1988) 5’

Mira Benjamin (violin) Bridget Carey (viola) Mark Knoop (accordion)

James Opstad (double bass) Heather Roche (bass clarinet)

2 Seven (1988) 20’

Mira Benjamin (violin) Bridget Carey (viola)

Simon Limbrick (percussion) Anton Lukoszevieze (cello)

Siwan Rhys (piano) Heather Roche (clarinet)

Nancy Ruffer (flute)

3 Seven2 (1990) 52’

George Barton (percussion) Simon Limbrick (percussion)

Anton Lukoszevieze (cello) James Opstad (double bass)

Heather Roche (bass clarinet) Nancy Ruffer (bass flute)

Barrie Webb (bass trombone)

disc one

1 Five (1988) 5’

Bridget Carey (viola) Mark Knoop (accordion) James Opstad (double bass)

Joe Qiu (bassoon) Heather Roche (bass clarinet)

2 Five2 (1991) 5’

Raymond Brien (clarinet) Peter Furniss (bass clarinet) Simon Limbrick (timpani)

Christopher Redgate (cor anglais) Heather Roche (clarinet)

3 Five5 (1991) 5’

Raymond Brien (clarinet) Peter Furniss (bass clarinet)

Simon Limbrick (percussion) Heather Roche (clarinet) Nancy Ruffer (flute)

4 Fourteen (1990) 20’

Chloe Abbott (trumpet) Mira Benjamin (violin) George Barton (percussion)

Raymond Brien (bass clarinet) Bridget Carey (viola) Mark Knoop (bowed piano)

Simon Limbrick (percussion) Anton Lukoszevieze (cello) Chihiro Ono (violin)

James Opstad (double bass) Heather Roche (clarinet)

Nancy Ruffer (flute & bass flute) Laetitia Stott (horn)

5 Five3 (1991) 40’

Bridget Carey (viola) Anton Lukoszevieze (cello) Gordon Mackay (violin)

Chihiro Ono (violin) Barrie Webb (trombone)

disc three

1 Five (1988) 5’

Mira Benjamin (violin) Bridget Carey (viola) James Opstad (double bass)

Joe Qiu (bassoon) Heather Roche (bass clarinet)

2 Five4 (1991) 5’

George Barton & Simon Limbrick (percussion) Heather Roche (clarinets)

3 Thirteen (1992) 30’

Chloe Abbott (trumpet) George Barton (xylophone) Mira Benjamin (violin)

Stuart Beard (tuba) Bridget Carey (viola) Simon Limbrick (xylophone)

Anton Lukoszevieze (cello) Chihiro Ono (violin) Joe Qiu (bassoon)

Christopher Redgate (oboe) Heather Roche (clarinet)

Nancy Ruffer (flute) Barrie Webb (trombone)

4 Six (1991) 3’

George Barton & Simon Limbrick (percussion)

5 Ten (1991) 30’

Mira Benjamin (violin) Bridget Carey (viola) Mark Knoop (piano)

Simon Limbrick (percussion) Anton Lukoszevieze (cello)

Chihiro Ono (violin) Christopher Redgate (oboe) Heather Roche (clarinet)

Nancy Ruffer (flute) Barrie Webb (trombone)

disc four

1 Five (1988) 5’

Raymond Brien (clarinet) Pete Furniss (bass clarinet)

Joe Qiu (bassoon) Christopher Redgate (oboe) Heather Roche (clarinet)

2 Eight (1991) 60’

Chloe Abbott (trumpet) Stuart Beard (tuba) Joe Qiu (bassoon)

Christopher Redgate (oboe) Heather Roche (clarinet) Nancy Ruffer (flute)

Letitia Stott (horn) Barrie Webb (trombone)

3 Four5 (1991) 12’

Raymond Brien (clarinet) Pete Furniss (bass clarinet)

Joe Qiu (bassoon) Heather Roche (clarinet)

John Cage’s number pieces

In the last five years of his life John Cage composed more than forty number pieces. This box set contains realisations by Apartment House of thirteen of them - all the works for mid-size ensembles (from Five to Fourteen), with Four5 added as a coda on the final disc.

The titles of the pieces simply indicate the number of players, so both Seven and Seven2 are septets, with the superscript number indicating that Seven2 was the second piece in the series for seven performers.

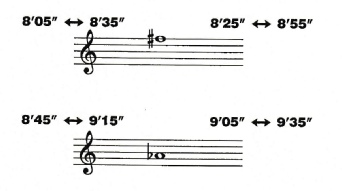

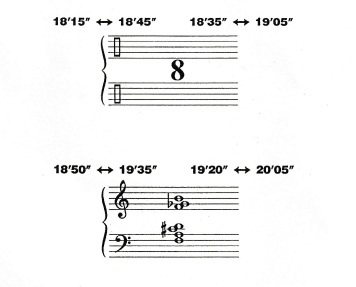

None of the number pieces has a time signature, bar lines or a conductor. The musicians decide individually when to play using a stopwatch and a system of ‘time-brackets’ which Cage had developed, though the way the sound brackets operate changes over time, generally becoming looser and more flexible in the later works. In some of the earlier pieces Cage occasionally uses fixed time brackets, indicating precisely when a musician should start and finish playing a particular note. But most of the time – and in all of the later pieces – the musicians choose when to start and stop within flexible time brackets, with the numbers on the left indicating a time within which the note must start, and the numbers on the right indicating the period within which the sound should stop. (See illustration 1)

Cage entrusts to the musicians the ability to make choices about when to play, and, in almost all the pieces, Cage also allows the musicians to choose how loud or soft to play each note, though usually with the stipulation that if they play loud, the sound should be short, whereas softer sounds can be long or short. This openness and flexibility about dynamics and when to play means that every performance of a number piece is unique.

Harmony

The number pieces constituted an unexpected turn in Cage’s output, a late flowering of music which is often quiet and meditative, and much less angular and abrasive than most of his compositions of the previous 40 years. Cage himself wrote that “after all these years, I am finally writing beautiful music.” In his doctoral dissertation on the number pieces, An Anarchic Society of Sounds, Rob Haskins argues that they constitute Cage’s “reconciliation with harmony”.

As a young man in the late 1930’s, Cage had briefly studied composition with Arnold Schoenberg. He later developed a famous anecdote about how they had clashed in their approach to harmony:

“I certainly had no feeling for harmony, and Schoenberg thought that that would make it impossible for me to write music. He said, "You'll come to a wall you won't be able to get through." I said, "Well then, I'll beat my head against that wall." I quite literally began hitting things, and developed a music of percussion that involved noises.”

It’s a good story, and almost all of Cage’s music does studiously avoid conventional classical notions of harmony. But that doesn’t mean that Cage was always oblivious to, or uninterested in, pitch and harmony. In an interview about Cage in 1982 Morton Feldman said “He’s bluffing. He has impeccable ears.” Rob Haskins argues that by the time Cage was writing the number pieces, he had “a changed view of harmony”. If he still wasn’t interested in classical rules, he was moving towards an idea of harmony as an omnipresent co-existence of sounds. As he said in an interview with Joan Retallack a few months before his death in 1992: “Harmony means that there are several sounds being noticed at the same time, hmm? It’s quite impossible not to have harmony, hmm?”

In 1990 Cage was invited to lecture at Darmstadt for the first time for 35 years. His talk, delivered as a series of mesostics, suggested a new approach to harmony:

“ alTernatives

to Harmony

lifE spent finding them beating my head

against a wall now haRmony

has changEd

its nAture it comes back to you it has no laws

there is no alternative to it how Did that happen

you could call iT

anarcHic harmony”

This notion of ‘anarchic harmony’, of pitches and sounds simply co-existing, and thereby establishing de facto relationships in a non-rule-bound way, is fundamental to much of what I enjoy about the number pieces. Given the musicians’ freedom to choose when and how long to play, it would be possible to produce hyper-minimalist versions of most of the number pieces, with short soft sounds and long pools of silence. At the time Cage composed the pieces, it was still a radical and unusual idea to include silence as part of a composition. Nowadays, after twenty-five years of Wandelweiser music, this is no longer the case, and I am much more interested in hearing the ‘anarchic harmony’ of different pitches sounding together in unpredictable ways. So for this box set we agreed that the Apartment House musicians would play relatively long within the time brackets, letting their notes rub up against the pitches of the other instruments. While some of the most sparse scores (especially Five3) inevitably do have periods of silence, in general we minimised the silences and enjoyed the unusual harmonies that resulted.

Chance

Cage famously started using chance procedures in his compositions in the early 1950’s. If the feel of the number pieces appears to be a new turn in his music, the number pieces are nonetheless typical in their use of chance procedures. Both the pitches and the timings of the time-brackets within which those pitches are sounded, were determined randomly. Whereas in the early days Cage mostly used the I-Ching to generate musical material on a random basis, by the time he composed the number pieces he was using computer programmes developed by his assistant Andrew Culver. This was much less labour intensive, and allowed him to take on a large number of commissions as he approached his eightieth birthday.

However, as in his earlier ‘chance’ pieces, randomness in Cage always operates within certain parameters, and his selection of those parameters is partly what gives each piece its shape and character. Cage spoke of this initial setting of parameters as ‘asking questions’. The random generation of material then fills in a set of possible ‘solutions’ within the horizon Cage has established, and the choices of the musicians finally make one of these myriad possibilities a reality. But the use of chance and randomness are not a sign of indifference to the actual sounds produced. In several of the pieces in the box set, while the particular pitches may be being determined randomly by a computer, they are being selected from within a very limited range of the possible pitches that each instrument could potentially play. So, for instance, all the pitches in Five, Four5 and Five4 are within a range of just over two octaves, and in, eg, Thirteen and Ten many of the instruments remain within a much more restricted range than this. And the frequency with which particular pitches recur in some of the parts suggests that the randomised system was weighted towards certain pitches or pitch relationships. While this is not harmony in the classical sense, Cage is operating some kind of system which means that the instruments are likely to create certain patterns when they sound together, and it is partly this which gives each piece its particular sonic character.

Cage and Feldman

The first of the number pieces, Two, was premiered in December 1987, just three months after the death of Morton Feldman. Some people have speculated that Feldman’s death somehow allowed Cage to compose more ‘beautiful’ music, as if Cage moved in to fill the space that Feldman had vacated. I’m not sure if this is the case, but the comparison with Feldman’s music is perhaps inevitable, especially given that the two had been friends since 1950. The gently shifting patterns and gorgeous arpeggios of Feldman’s late music give it an immediate, seductive attractiveness that Cage’s music doesn’t match, or attempt to match. The number pieces offer a starker, less luscious kind of beauty – with sounds existing like rocks across a moorland landscape. In the past ten years or so, Feldman has become part of the classical canon, with performances at major concert halls, sometimes by stars of the classical music world. Cage remains an outsider and the number pieces are performed much less often, but for me their stark beauty is just as intense as the very different beauty of Feldman’s music.

Performance

For a long time, Cage composed mainly for musicians who he knew personally, and who were committed to his work. When his music was performed by mainstream classical ensembles, he sometimes had difficult experiences. Musicians would interpret the openness of his scores as meaning ‘anything goes’, wouldn’t follow his instructions, and introduced theatrical elements that treated the music as a joke. While Cage wasn’t always averse to humour or theatricality in music, on these occasions he felt that a fundamental disrespect underlay the musicians’ attitudes and interpretations.

In general, by the time he was writing the number pieces, the situation had improved. Even if the mainstream classical world still regarded him with suspicion as an enfant terrible, within contemporary music circles he was widely regarded as an elder statesman of the avant-garde, and by the late 1980s he felt able to write for a large variety of ensembles with the expectation that they would interpret his music seriously and respectfully.

Cage wanted performances of his music to express his social ideals of an anarchist community, in which individuals are entrusted with a good deal of responsibility and collaborate together on a basis of equality. In the instructions for 101 he writes “A performance of music can be a metaphor for society. In this music there is no conductor. There is no score.” He also wrote: “I must find a way to let people be free without being foolish. So that their freedom will make them noble…my problems have become social rather than musical.”

Although the pieces in this box set were all performed and recorded in the years immediately before or after Cage’s death, few of them have been played in the past 10 or 15 years, and I feel that they have become somewhat neglected. In the meantime, the contemporary music world has moved on and developed, and I felt that new realisations of the pieces nearly thirty years on from Cage’s death might bring something fresh to the pieces. Cage described his system of composing with time brackets as ‘earthquake-proof’, meaning that its flexibility prevented the music from becoming too fixed, or attached to one particular style of interpretation. Having worked with Apartment House on many recordings in the past few years, I believed that they would discover things in some of the pieces that hadn’t been apparent in previous recordings.

Apartment House was formed just a few years after Cage’s death, taking their name from one of his later compositions. They have a 25-year history of performing Cage, and are particularly well-suited for playing the number pieces as they are not only excellent instrumentalists, but are also exceptional when it comes to works in which the players have some freedom of interpretation.

With each piece we agreed beforehand the outline of a particular approach; a rough guideline for dynamics, and an agreement not to use emotional or theatrical styles of playing. Part of the preparation was listening to all the existing recordings of the pieces, and thinking about what worked and what didn’t. From then on it was a process of discovery, with the details of each piece’s particular character emerging only in the playing. Some of the realisations have come out very different from previous recordings. Especially in Seven2, Thirteen, Five4 and Eight, I think that the Apartment House musicians have discovered things that open up the pieces in strikingly new ways.

Cage doesn’t give any instructions in any of these scores as to whether or not the musicians should work independently of each other. While they are entrusted with choosing the dynamics and exact timings, it is not clear whether these choices should take into account what the other musicians are doing at the time. For these recordings we left this open, so that some of the musicians prepared precise timings in advance which they would keep to whatever was happening in the music, whereas others left this open and chose exactly when and how loud to play by listening to the development of the ensemble sound in the moment.

It would be wrong to suggest that all of the number pieces are soft, tranquil and beautiful. To varying degrees, some of the scores resist such interpretations, involving wilder, louder or rougher elements. For instance, Seven, which is one of the few pieces where dynamics are specified, has a piano part which is often marked forte, in contrast to the other instruments, which are mainly piano or mezzopiano. In Ten the piano part contains a lot of sounds made on the body of the instrument, introducing noise elements into the music. And the string instruments in Five3, Seven and Ten are instructed to play in unorthodox ways – sul ponticello, col legno tratto or with loose hair on the bow – such that a pure string sound is clearly not what Cage was after. This gives a roughness, tension and unpredictability to some of the pieces which belies the common perception of them as uniformly placid and meditative.

Percussion

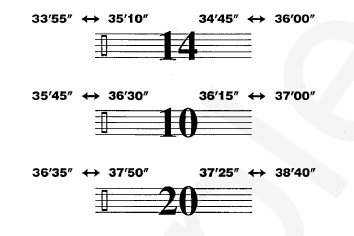

As Cage’s anecdote about Schoenberg makes clear, percussion has a central place in much of his music, and is one of the principal ways in which he introduces noise elements and ‘unmusical’ sounds into his work. In two of the pieces in this box set the percussion parts are for pitched instruments which operate much like the other instruments (the xylophones in Thirteen and timpani in Five2). However, in the other pieces the percussion parts work differently. The time brackets simply contain numbers, each one representing a different sound which the percussionist is free to choose. (See illustration 2 opposite)

Cage offers suggestions as to the kind of instruments or sounds that might be used in each piece (eg friction sounds in Seven, resonant metal percussion in Seven2, and ‘not overly resonant’ sounds in Five4), but ultimately he leaves the choice of instrument to the percussionist(s). This gives the percussionists even more freedom / responsibility than the other players, as their instrument choices can have a major effect on the overall sound of the piece, especially in works like Seven2 and Ten, where percussion may be sounding most of the time.

Covid-19

The box set was produced in the year of the plague, between August 2020 and May 2021. This inevitably created difficulties. Because of Covid restrictions and quarantine regulations, we weren’t able to record every piece as if ‘live’. In a few of the pieces one or two parts had to be recorded separately and edited in in post-production. This wasn’t ideal, and I would never have chosen it as a way of working, but it was unavoidable. However, in just a couple cases the process of constructing the piece through combining tracks that had been recorded separately actually opened up the music in interesting ways, enabling us to focus right in on details of the score, and it has arguably improved the end product.

History

I remember the impact that the number pieces had on me when I first started to hear them in the 1990’s. I had been listening to what was then called ‘avant-garde music’ since the early 70’s, when as a teenager I discovered Stockhausen, Boulez and Derek Bailey all at the same time. I bought as many discs as I could afford of both composed and improvised music, but by the early 1990’s my initial enthusiasm had started to wane. The soundworld of post-war serialism no longer seemed fresh and exciting, and I felt that - over twenty years on from its beginnings - improvised music too had got stuck in a rut. In those pre-internet days, new music travelled slowly around the globe, but in the early to mid-90’s I began to hear a number of things which dramatically rekindled my enthusiasm for contemporary music: Cage’s number pieces, the late music of Luigi Nono, and the work of Morton Feldman. If I had become dissatisfied with most of what contemporary music was offering, I had no idea about how or where anything new or more exciting might emerge. But as soon as I heard late Nono, Feldman and Cage’s number pieces, I knew that these were new directions I had been waiting for. As ever for me, it wasn’t the concept or ideas underlying the music which appealed to me; it was simply the sheer sensual pleasure that listening to the music offered.

It obviously wasn’t just me; by the mid-1990’s the Wandelweiser Composers Collective had formed, partly on the basis of a shared enthusiasm for Cage’s number pieces. And around the same time some improvisers began to turn towards quietude, which, by the turn of the millennium, had brought a new energy to the music through the emergence of ‘lower-case’ or ‘minimalist’ improvisation.

Philip Thomas

Because they made such an impression on me at the time, I have wanted to produce a box set of Cage’s number pieces for years, but given the number of musicians involved, it is an expensive project. What made it possible is the money that came into the label from the success of Philip Thomas’s Morton Feldman Piano box set. Philip has been my closest musical friend for years – both geographically (he lives just a mile from my house), but also because I have talked more to him about music – and especially John Cage – than anyone else. Philip has appeared on more Another Timbre CDs than any other musician, and his enthusiasm, generosity and intelligence have been fundamental in helping shape the development of the label. Three of the pieces in this box set have substantial piano parts, and are all in different ways like little piano concertos (Seven, Ten and Fourteen). I obviously intended and expected that Philip would be the pianist for these recordings, but, very sadly, ill health made that impossible. The box set is dedicated to Philip.

Simon Reynell, May 2021

Illustration 1: from the trumpet part of Eight

From the Percussion 2 part of Seven2

Apartment House recording Cage’s Number Pieces

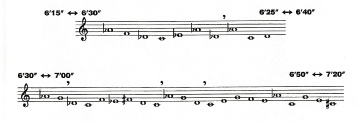

Illustration 3, from the Violin 1 part of Five3

Illustration 4, from the oboe part of Thirteen

Illustration 5, from the piano part of Ten

The pieces

Five was one of the earliest number pieces, and is the only one in this box set with open instrumentation. Across its five-minute duration, each player has just five time brackets with between one and three sounds in each. Cage includes an instruction that he also uses in other pieces, that the notes “should be brushed in and out rather than turned on and off”. Unlike in almost all the other pieces, dynamics are given, and are all within a range from mezzopiano to pianissimo, making this a particularly placid piece. There is one fixed time bracket for all the players, between 2:15 and 2:45, producing a gentle crescendo in the middle of the piece, which makes it quite distinctive. The range of pitches used is confined to just over two octaves. In this box set there are four realisations of Five, one at the start of each disc, all with slightly different instrumentation. This gives a sense of how, even though every realisation of one of the number pieces is unique, each piece also has a particular character which can often be discerned across different versions.

Five2 is like Five insofar as it is composed for five instruments and is five minutes long. Both clarinet parts and the bass clarinet have five time brackets, each containing between one and three notes, whereas the English horn / cor anglais and timpani have just three time brackets. It is another serene and fairly minimal piece. The timpanist only starts half way through and plays just three notes. The presence of the timpani and bass clarinet means that the range of pitches is much wider, and stretches much lower, than in Five.

Five5 is also five minutes long. Each instrument has five, six, or seven time brackets with just one note in each bracket. This is the first piece in the box set where the percussionist chooses their own instruments rather than playing given pitches (as on Five2). The percussionist has to choose five sounds, with the sole stipulation being that if the sound is long, it must “sound throughout the duration, not as though repeatedly struck, but as though sounding continuously.” Although the percussion sounds are not being produced by pitched instruments, every sound has a pitch and so the choice of percussion instruments contributes to the ‘anarchic harmony’ of the piece as a whole.

Fourteen is like a strange piano concerto. The piano is much more active than the other instruments, but is ‘bowed’ throughout, i.e. sounded not from the keyboard, but by the pianist pulling horsehair across the strings. This unusual, haunting sound is very unpredictable, and mostly very quiet. Cage specifies that “the bowed piano part is not to be covered up” by the other instruments, and, as the piano is sounding through most of the piece, this means that the general dynamic has to be very soft. Cage writes “Let the bowed piano part be an unaccompanied solo, one which is heard in an anarchic society of sounds”. Most of the other instruments play only a few notes across the twenty- minute duration (on average about twelve notes each), and gaps of about three minutes between time brackets are fairly common (the double bass has one pause of over nine minutes!) The two percussionists choose their own instruments, but “they should all be very resonant and are bowed or played with a tremolo such that individual attacks are not noticeable.” The prominence of the bowed piano sound, and the way the percussionists work alongside this, makes Fourteen probably the most textural of the pieces in the box set. (In this recording the flautist played both the part for flute/piccolo and the part for bass flute, as the time brackets for the two parts hardly overlap at all)

Five3 is written for trombone and string quartet, and employs a microtonal notational system which Cage developed, using small arrows beside the notes in the score to create six steps between each semi-tone. This didn’t come from a particular interest in, say, just intonation, nor a keenly felt concern for extreme pitch accuracy, but was, I think, more a way of making the music strange for both the musicians and listeners. In addition to the unusual pitch relationships, there are odd little glissandi, and the string instruments are often instructed to play either sul ponticello (near the bridge, which tends to bring out high harmonics) or sul tasto (over the fingerboard, giving a soft, pinched quality). This often gives the string sounds a tense fragility. It is the most sparse of the pieces in the box set, and there will be several fairly long periods of silence even if the musicians play to the outer limits of the time brackets. To some extent these silences make Five3 peaceful to listen to, but the strange quality of the instrumental sounds and the unusual pitch relationships bring with them an underlying tension which is never resolved. (See illustration 3 opposite)

Seven is one of the earliest of the number pieces. As in Five, dynamics are specified and each player has one time bracket which is fixed. Like Fourteen, it is a kind of piano concerto in that the piano is by far the busiest of the instruments, with several notes or chords in each time bracket, while the other instruments have just one or two pitches per time bracket. In this case, the piano is also the loudest instrument; many of its notes are marked forte, whereas the other instruments range from piano to mezzoforte. The string instruments are instructed to play col legno tratto (with the side of the bow, so that both the hair and the wood of the bow touch the strings). They are also asked to play with loose bow hair, creating an instability and wildness in the sound. The percussionist uses just four sounds, which they can choose, but all of which must be produced by friction. These features combine to make it one of the least tranquil of the number pieces.

Seven2 is a long piece in which the two percussion parts are the most extensive and active. The Percussion 2 part in particular is very busy, using twenty different sounds, and, if the time brackets were played to their full length, the second percussionist would play continuously for the first twenty-seven minutes of the piece, and for all but six of the fifty-two minute duration. For this realisation we made the percussion parts the bedrock on which the other instruments built. The other instruments are all in the bass register (cello, bass clarinet, bass flute, bass trombone and double bass), giving the piece a distinctive and dark colour. There is only one note per time bracket in each of the parts, making it one of the least busy of the pieces. In most realisations of the piece there are substantial periods of silence, but in this case the percussionists cover a lot of the potential gaps by playing very long sounds. Cage instructs that the percussion instruments “should all be very resonant” and, while the percussionists are free to choose what sounds to use, he suggests a series of mainly metal instruments - “Chinese and Turkish cymbals, Japanese temple gongs, tam tams, thunder sheets, bass marimba tones and Balinese gongs.”

Five4 was composed for soprano and alto saxophones and three percussionists. In this realisation both saxophone parts are played on the clarinet, and the three percussion parts are shared between two players. Uniquely with these pieces, Cage’s instructions for the percussion sounds state that the instruments should be ‘not overly resonant’, and he specifies the number of times each instrument should be struck. This suggests very short sounds, though he also says that ‘dynamics and durations should be extremely varied’ across the piece as a whole. In this realisation the variety of dynamics occurs mainly in the percussion parts, while the variety of duration is achieved between the short percussive sounds and the longer clarinet notes.

Thirteen was the last work that Cage completed, and has a couple of distinctive features. Many (though not all) of the time brackets contain long threads of up to 20+ notes, whereas in most of the number pieces the time brackets contain between just one and three notes. Also, many of the instruments have a strikingly small pitch range, in most cases covering less than one octave, with certain notes being repeated frequently. This creates a hypnotic, circular feel, with the same pitch areas recurring again and again. The percussionists play the same part, all within an octave at the bottom end of the xylophone, but are instructed not to play in unison. The xylophone part is particularly busy, and has almost twice as many time brackets as some of the other instruments, with the two players together creating a sort of continuo accompaniment. In this recording the piece has a lusciousness that no-one expected until the musicians started playing. (See illustration 4 opposite)

Six is the shortest of all the number pieces. Written for the Slagwerk Den Haag percussion group, it has a restless quality rather than the serene mood of many of the number pieces, with thirty different sounds being used across its three minute duration. Choice of instruments is left to the musicians with very little guidance from Cage. For this recording the percussionists took three parts each, recorded them as three duo tracks, and then simply superimposed them on top of each other, giving a high degree of indeterminacy to the realisation.

Ten uses the same microtonal system as Five3, in which Cage used little arrows in the score to divide each semitone into six steps. Again, I think that this didn’t come from a concern for hyper-accurate intonation, but was simply a way of setting up a multiplicity of unusual pitch differences, and making the music feel strange. As in Thirteen, most of the instruments have some time brackets that contain long threads of notes, often no more than a tone apart, like bizarre little microtonal melodies that flutter and circle round the more sustained notes. The piano and percussion parts are markedly different from the other instruments, and in some ways Ten is like a concerto for piano and percussion. The piano part combines chords of six, seven or eight notes with noises made directly on the strings or on the body of the instrument. For the latter, Cage uses the same system as in the percussion part, where each time bracket is assigned a number, and the pianist chooses a particular sound for each number. This introduces a noise element in contrast to the microtonal soundworld of the other instruments, and in this realisation the percussionist also uses noise-like rather than pitched sounds, acting like a partner to the piano in sometimes disrupting the forlorn beauty of the sustained tones played by the rest of the ensemble. (See illustration 5 opposite)

Eight was commissioned by The Trisha Brown Dance Company as an accompaniment for a ballet piece. Composed for brass and woodwind instruments, it is the only piece in the box set in which dynamics are completely free, so that even long sounds can be played loud (this is also true of Fifty-eight, another larger piece for brass and woodwind instruments). It is also unique in that Cage invites the use of crescendi and diminuendi. For this recording we agreed that there should be at most just one crescendo and diminuendo per note in order to avoid a kind of wah-wah effect, which felt wrong for the music. All the instruments have a lot of time brackets (roughly 80-90 across the hour’s duration), but with just one note in each bracket. Cage writes that “intonation may not be agreed-upon”, so allowing for slight variations in tuning between the instruments. Eight has only been recorded once before, and has been performed very rarely, so going into the recording session we had little sense of what the piece was. Listening to what emerged was a revelation.

Four5 was composed for saxophone quartet, but is performed here in a version for two clarinets, bass clarinet and bassoon. Each time bracket contains a single note, making it another relatively sparse piece in which silences are likely to occur. As in Eight, Cage specifies that the players should not tune together beforehand, so that intonation will be slightly varied and “a unison will be a unison of differences.” Although it is scored for instruments with different registers, the range of pitches through the piece is restricted to just two octaves.

In addition to the recordings on the four CDs in the box set, there are downloads available of alternative versions of three of the pieces: Seven, Four5 and Five. You can download them for free / on a ‘pay what you want’ basis from Another Timbre’s Bandcamp page: anothertimbre.bandcamp.com/album/number-pieces

Produced and recorded by Simon Reynell at Goldsmiths Music Studio, Henry Wood Hall, The University of York, Loughton Church and The Old School, Starston between August 2020 and May 2021. Additional recordings by Simon Limbrick, George Barton and Chloe Abbott, with thanks.

Thanks to all the musicians of Apartment House for their commitment and extraordinary musicianship.

Cover artworks & design by Arvinda Gray, with many thanks

The scores of John Cage’s number pieces are published by Edition Peters / Henmar Press