Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

at116 Olivia Block

New work for piano and organ (2017)

CD copies have sold out, but downloads are available here

Interview with Olivia Block

How did you develop the work on your CD? Was it through-composed or improvised, or was it a combination of the two? And is the method you used for this piece fairly typical of your compositional practice?

This suite was created over a span of several years. I developed techniques inside piano through rehearsals and performances, sketched the basic ideas out--the motives, physical materials, etc., leaving a lot of room for improvisation between the composed bits. I think of the suite as somewhat modular. I can switch sections around while key features, like patterns on the keys in each section, are composed.

There are certain aspects that are unpredictable by nature. For instance, the resonant notes inside the piano, amplified through the contact mics and mini speaker, lead the note choices I play in the keyed patterns.

So in terms of live performance, each piano and the materials I place inside the piano become key factors. The score sets these processes in motion, but leaves room for my spontaneous reactions to the natural acoustic phenomena within certain boundaries.

Why did you choose to present the piece without a title?

In contrast to most of my recordings, these pieces are relatively unedited. I recorded them live at Electrical Audio studio here in Chicago, only adding a slight amount of post-production detail. Most of the extra production intervention happens during the performance with a micro-cassette recorder, played back inside the piano.

So the lack of title reflects the fact that the suite is more direct, and in a sense, bare, of layers or extra elements. It’s basically just me playing piano and objects. This is the first time I have worked with a co-producer, Adam Sonderberg. Adam initially suggested leaving the title blank and I liked the idea and went with it.

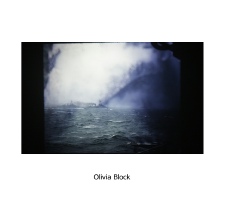

The image on the CD cover is striking. What is it, and does it have a connection to the music?

The image is a projection on a wall of a custom slide I created from two layered 35mm “found” slides from my slide collection. To me, the image is related to the suite in terms of mood and impression. The feel of the blue and white, and the images of the water match the timbral qualities and pacing of the suite.

What is your musical background and training? And how did you come to experimental music?

I have a degree in biological anthropology, but I also attended a music conservatory and art school for sound. I think of myself as auto-didact, though.

My initial training was when I was really young in Austin, Texas, playing in bands and working as an assistant in recording studios.

I started listening to experimental collage and noise music when I was still in bands. I also discovered the music of Scelsi, Annea Lockwood, Phil Niblock, Ligeti, Jim O’Rourke, Harry Bertoia and the horn and cymbal music from Tibetan Buddhist monks.

I got a four-track recorder and started making solo tape collages. The band I was in played the collages in between songs. Then I wanted to quit the band and focus solely on the studio pieces. I bought a cornet at pawnshop and then only wanted to play cornet instead of guitar.

At around that time in Texas I met Seth Nehil and John Grzinich. We started a trio, Alial Straa, performing and improvising in unconventional, acoustically rich locations. We performed in a drainage tunnel and used the rocks and leaves there as instruments. We made field recordings with a portable DAT recorder and used them in shows with amplified objects.

As I progressed in my solo practice, I wanted to work with ensembles of musicians, adding a different live component to my performances. When I moved to Chicago in the late nineties, I became connected with Jim O’Rourke and the improvisers in his orbit like Jeb Bishop and Kyle Bruckmann.

At first I mostly worked with improvisers, but over time, I composed scores for the musicians to play, which I could then record and add to my studio pieces later. After that, my ideas for scores became increasingly complex, and the combinations with studio-based sounds and musicians became more elaborate. I decided to gain a “formal education” in music composition.

I became fixated on making orchestral music. I thought about it and talked about it constantly. I wanted to study music formally because I needed to learn proper notational techniques for that medium. When I was studying at the conservatory I requested to be paired with teachers who used conventional notation. I wanted to know where to put the slurs and indentations properly.

I could then create pieces for the orchestral reading sessions and try out ideas. I started thinking about how I wished orchestral music allowed for more improvisation in rehearsals, and thought about the social structures of music-making which contributed to my interest in anthropology.

I had several solo recordings released before attending music school. I couldn’t finish at the conservatory because my touring schedule got in the way. I was older than the students there. I finished a degree in anthropology at Northwestern instead, attending school between my music-related trips.

Your work varies from purely electronic works, through live improvisation to fully scored orchestral pieces. Are you happy working in all the genres your work spans, or do some of them feel closer to you?

Sometimes I wish I had a narrow focus in my practice. I think it would be easier to explain myself to people! But I keep expanding into different aspects of sound and music and other media. To me, these different branches all express my own sensibility and interests, so they related in my mind.

I feel most comfortable in my studio working with recordings and electronic processing techniques. I love sitting down with headphones or in front of speakers and listening to ideas, changing them, listening, and so on.

I am more adept at listening than at reading notation, so the least comfortable process for me is notating pieces, particularly if I am using conventional techniques (I often combine conventional and “experimental” notation techniques).

It takes me a long time to score something that I could simply tell a musician to do in a few minutes. Then, when I listen to the notated idea performed, it doesn’t sound right and I need to go back and rethink the scoring techniques. The process feels inefficient and complicated, but necessary, of course.

Often I finish notating a score after I record the piece and all of the trial and error with musicians or myself is worked out. I listen to rehearsal recordings or concert recordings and notate the piece in retrospect.

Now I am using old science experiments and other found texts as scores for performed pieces, which is a little more comfortable. This part of my practice is the least related to my studio work, in that the score leads the entire the process, whereas I usually hear a sound from my studio recordings or imagine sounds, then want to notate afterwards. That is the reverse of the ‘norm’ I guess.

From across the ocean, Chicago seems to be quite a vibrant centre for experimental music of various kinds. How do you see it, and do you feel part of a local ‘scene’?

The Chicago experimental music scene is thriving now. We are in a moment here where there are competing experimental or new music performance events almost every night of the week at various venues in town. It’s a great problem to have. I travel a lot and when I am home I stay in a lot and work in the evenings, but I still feel very connected and supported. There are many organizers, musicians and composers I love here.

Reviews

“The CD cover for Olivia Block’s new solo release on Another Timbre is spare, even for the standards set by that label. The CD has no title, the three pieces are simply titled I, II, and III, the only annotations is that Block is credited with “piano and organ” and it is noted that the recording was made during a single session in Chicago. The structure of the CD has a certain palindromic simplicity as well, with the first and third pieces running a bit over 13 1/2 minutes and the central piece running exactly 8 1/2 minutes. Take a listen and the music strikingly aligns with the graphic austerity of the cover. Each piece delves deeply in to a particular timbral range, and each explores the nuances of the piano as both sound source and resonator. At the core of each is a sense of sonic investigation, setting up the piano with preparations and treatments that push the instrument and the way it interacts with the acoustics of the recording studio.

In an interview on the Another Timbre site, Block explains her approach like this. “This suite was created over a span of several years. I developed techniques inside piano through rehearsals and performances, sketched the basic ideas out – the motives, physical materials, etc., leaving a lot of room for improvisation between the composed bits. I think of the suite as somewhat modular. I can switch sections around while key features, like patterns on the keys in each section, are composed. There are certain aspects that are unpredictable by nature. For instance, the resonant notes inside the piano, amplified through the contact mics and mini speaker, lead the note choices I play in the keyed patterns. So, in terms of live performance, each piano and the materials I place inside the piano become key factors. The score sets these processes in motion, but leaves room for my spontaneous reactions to the natural acoustic phenomena within certain boundaries.”

The first piece starts with crystalline, percussively struck pairs of notes at the top of the keyboard, with space left to allow the decay of the tones to hang. Gradually, Block moves the motifs down to the middle register of the piano, introducing rich chords and the jangling sound of prepared strings while calling up ghost tones and shadowy textures to fill in at the edges. Pacing here is paramount, as she parses out each figure and chord progression, accentuating sharp attack and maximizing the resulting overtones and resonances. Toward the final section of the piece, layers begin to build with a gauzy transparency, bringing to mind the way that light radiates through stained glass, filling a room with the resultant chromatic tints.

The second piece makes far more use of preparations with quietly ticking motors, percussive flurries, and struck strings accruing into a shimmer of detail. The pace is much more rapid as well, and the gestures of Block’s playing are more apparent, choreographed against the low rumble of bass chords. The patter and hum of incidental sounds also emerge, including the low hum of organ and the pings and twangs of the strings projected back in to the instrument. In the final section of the piece, volume and density peak, opening up to squeaks and creaks against the low buzz of the organ. Here traces of mechanical sounds accentuate the duality of the piano as string instrument and percussive mechanism.

The final piece expands the sonic spectrum further, accentuating the lower registers and utilizing abrasions and filtering of the natural string resonances. The dark colorations of organ are also more pronounced. The dusky registers have a decisive impact on the internal feedback loops of mic’d and amplified aural vestiges of the elemental sounds of the piano, providing granular shadings that fill out the sound palette. Like the first piece, the pace is stately and methodical, with each chord placed with mindful purpose within the overarching flow. In the last third, the sharp, glassy notes of the opening piece are gradually incorporated, bring the suite full circle. Block often works with multi-channel installations and one can hear how that sensibility comes through in the intimate format of this recording, using the placement of treatments and amplification of the piano with an analogous approach. Adam Sonderberg’s meticulous production is another element worth noting as he captures the playing with brilliant spatial clarity.

Michael Rosenstein, Point of Departure

“Chicago-based musician Olivia Block has been notably subtle and successful in blending environmental recordings with instrumental voicings and electronic sounds. Her acute compositional ear responds to changes in the timbre of rustling leaves no less than to the percussive drama of a hailstorm. For some years she has brought that discernment and sensitivity to her exploration of the piano as an acoustic ecosystem, introducing various objects into its interior and using amplification to modify and expand its sounding range. On this untitled suite in three movements, essentially a live performance with minimal subsequent intervention, notes fall from the piano’s keyboard like water droplets from a ledge giving rise to sonic micro-organisms that take on a life of their own. Sparsely patterned tones spawn textures and shadings that open onto a far more mysterious musical biome. Strange beauty compounded by an enigmatically resonant cover image that Block has created too.”

Julian Cowley, The Wire

“Although this is her first appearance on the label, Olivia Block is definitely at home on Another Timbre. Having said that, whatever expectations listeners may have of Block, based on her past releases, the music here is likely to expand them. In particular, it is neither a purely electronic work nor a large ensemble of Chicago players improvising nor scored orchestral pieces. Instead, we get Block herself alone at a piano. The album sleeve is quite economic with information; the album title is simply Block's name; the music is untitled beyond its three sections—totalling just over thirty-five minutes—bearing Roman numerals. We are told that it was recorded in Chicago in February 2017, co-produced by Adam Sonderberg.

In interview, Block refers to the music here as a suite, adding that it leaves a lot of room for improvisation between the composed bits. She says that she thinks of the suite as somewhat modular and can switch sections around. As well as preparing the piano with objects inside, Block also employs a contact mike connected to a mini speaker and during the performance uses a micro-cassette recorder played back inside the piano. None of that is gratuitous gimmickry, but is all part of a well-crafted and thought-through composition that feels coherent and logical.

The three parts (movements?) contrast with one another but hang together as a whole that, due to the devices just described, occasionally displays a soundscape full enough to have been created by several players. At other times, Block is heard entirely alone at the keyboard, picking out dramatic single notes whose pure sound is mesmeric. Throughout, the music is fascinating and engaging, sure to attract listeners in and hold their attention. This album will appeal to existing Block aficionados and draw in many new ones.

John Eyles, All About Jazz

“Olivia Block is perhaps best known to Fluid Radio readers for her electroacoustic works such as “Aberration of Light” and “Dissolution”. This music draws on plenty of acoustic sound sources, but is generally constructed on a computer. However, the Chicago-based composer has also developed a live performance practice using acoustic keyboard instruments, specifically piano and organ, and it’s this work that features on her first solo recording for UK label Another Timbre. The first time I came across this aspect of Block’s music was at a concert at Café Oto earlier in the year, but the home recording gives perhaps a more distilled and focused impression of her intentions.

Like many contemporary performers, Block prepares her piano by inserting different objects between the strings and plays those strings in a number of non-traditional ways in order to coax different timbres from the instrument. Sudden, sharp stabs in the higher registers give way to quiet tentative phrases lower down; the constant juxtaposition of accented and effaced notes creates a mysterious, suspenseful atmosphere. Reverberation and the afore-mentioned preparations lead to interesting resonances, but Block also demonstrates how resonance changes with pitch through a lovely descent from one end of the keyboard to the other. She then moves on to play directly on the strings, emphasising the piano’s curious double status as both a stringed and percussion instrument with spindley, metallic, rapid-fire tingles and chinks.

The organ first enters as a very quiet hum, with strange, squeaky fireworks occasionally shooting off into the distance. A gentle pattering builds into frantic storm-like chattering, clattering, and scraping. Towards the end of the recording, a very low quiet tone is felt more than heard, drawing attention to the way these acoustic instruments sound in (and sometimes shake) a physical space. Block uses the full range of options at her disposal to animate the keyboards and the mechanical contrivances behind them, with extremes of dynamics, pitch, and timbral contrast all deployed. If anything, the results seem to me a little less singular and distinctive than her electroacoustic work — but there’s no doubting the quality of this music, or the attentiveness to the myriad possibilities offered by these instruments and the spaces in which they sound.”

Nathan Thomas, Fluid Radio

“Olivia Block does not make the same record twice. Of her three most recent albums, one uses grayscale sound to represent changes in light, another illustrates the unraveling of understanding with distorted recordings of therapy sessions and radio broadcasts and a third contrasts strings with concrete sounds to show you what gets thrown out on the way to making an orchestral production. They sound nothing like each other, but each is the product of relentless sound processing that invites a listener to wonder not just what they are hearing, but why it has been changed into something else.

At first this untitled CD sounds like a startlingly straight recording of Block at the keyboard. There are long stretches of unaccompanied piano, gorgeously played and immaculately captured in the adobe-bricked interior of Electrical Audio studio. Single notes radiate and sparse configurations turn in harmonious orbits, inviting you to luxuriate in their austere loveliness. But then you notice something behind the notes. Tiny, distant, unidentifiable sounds keep the listener from getting too comfortable, which is just as well given the disorientation in store. Over the course of the record’s three tracks Block uses typical post-Cage-ian hardware preparation, amplification, microcassette recordings of the performance in action, and some subliminal organ drones to transform the piano’s sound. The manipulator’s hand will not be stayed.

But to what end? The sounds never get so far from what you expect of a piano that you can’t tell where they came from, and the absence of titles suggests that this music doesn’t purport to be about anything, it just is. But just as Block used abstraction and magnification to take a hard look at the vanity of orchestral sound production, she applies similar methods to make an overly familiar instrument new again.”

Bill Meyer, Dusted

Photo: Tinnitus photography, with thanks

Photo: Jason Lascalleet

Photo: Jason Lascalleet

And more reviews…

“How do you compose through improvisation? Just let go and try not to think about it? Keep it as it is, or go back and revise? If you revise, do you cut back or elaborate? This new release by Olivia Block is an untitled, 35-minute suite of three movements, played on and inside a piano, with additional parts on organ and some electronics. She has stated that this piece was created over several years of rehearsals and performances. Musical material was developed, but in a way which left lots of space for improvisation, an open structure where placement of the composed elements was never entirely fixed.

The scope for improvisation is thus circumscribed. In doing so, the improvisation becomes of a piece with the composed elements, each seeking out a coherent context. At first, the piano sound predominates, with untreated and prepared piano notes combining with harmonic resonances. The central movement introduces contrasting percussive sounds from inside the instrument. The final movement returns to the keyboard but much sparser, with silences becoming more persistent and occasional intrusions of electronic distortion. Each time I listen to this CD, I hear the performance as an act of heightened responsiveness. Aesthetic decisions are made, but always in reaction to what is heard. Sounds are augmented, changed, reduced. It isn’t continuous, the changes are perceptible, the sounds and sections are clearly differentiated – still, the three movements play as an organic whole.”

Ben Harper, Boring Like a Drill

“Since the late 1990’s this Chicago based musician, electro-acoustic composer, & multimedia artist has been creating a body of often stark & moody work that sits somewhere between modern classical compositions, improv, and edgy sound art. Here’s a recent self-titled CD release on Another Timbe- which offers up a three tracks for piano & organ- and each is extremely skeletally-yet-eerier intriguing in it's use of the inside & outside of both instruments.

The release comes in the normal sparse Another Timbe house design of a white mini gatefold, and this features on its front cover a murky & dark picture of what looks like a boat out a sea having problems. And this is perfect for the work with-in, both highlighting the feeling of dark mystery & often angular unease about the tracks here.

The three tracks are simple entitled I-II, and each have runtimes between eight & thirteen minutes- with a total release runtime of spot-on thirty-five minutes. All three tracks are very stark & pared back sonic canvas- and they utilize a mix of drifting note hits & their dark reverb. Eerier piano string pickings, a selection of quiet knocks & fumbling. Silence or near silence, and every once in a while sudden & jarring mass of key bangs, more manic string pics, and barren-to-skittering percussive sounds.

The more musical moments- drift from doomy & descending, to fragile & melancholic, and there is a nice feeling of angular unpredictability to each of tracks unfold. Yet they never sound random or cluttered in their structure, and clearly, each track is both conceived & composed to create both tension, fleeting release, and angular beauty.

It’s really an album for either a very quiet room, or even better still headphones- so you can pick up every little subtle shift or moody micro tone detail in each of the tracks. I see little point in outlining each tracks unfold, as I feel that would very much take away from the experience of both each individual tracks & the album as a whole. But through-out Block keeps ones attention well & truly hooked- with the compositions blend of mood, and an ear for sonic invention & detail.

It must be a few years since I’d last heard any of Ms Block’s work, and I must say I have very much enjoyed this self-titled release- finding it reward in both its atmospheric & creative sound use.”

Roger Batty, Musique Machine