Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

Interview with Joseph Kudirka

I know very little about your background except that you studied at CalArts with James Tenney and Michael Pisaro. So can you tell us about how you came to experimental music and why?

I guess I have to answer your question in a roundabout way. For years, before I really considered myself to be a composer, I was a bass player. As a teenager, I was playing in local youth orchestras and playing electric bass in bands and things like that. I was just into weird music; really nerdy stuff, like jazz fusion and progressive rock. I had some inkling of experimental music first through those channels; I was into the Jamie Muir era King Crimson, and the Area lineup with Demetrio Stratos and Walter Marchetti, etc., as well as Fred Frith, Doctor Nerve/Nick Didkovsky, and the Russian band ZGA, who were on Chris Cutler's label for a few albums - I really liked them a lot. On the classical side of things, I was really into Schnittke, and I had a string quintet that did our own arrangement of an Arvo Part piece, and things like that… so, on the periphery of experimental music, but still pretty staid. I was lucky to have people around me to encourage this. Oh! I'd also started doing a lot of electronic music by that time. I had a sampler, and I had a sort of band that would do improvised gigs with synths, my sampler, a shortwave radio, and whatever else was on hand. I wasn't too aware of free improv, but I knew that what I was doing was more "out there" than the improvising pop bands I liked (The Grateful Dead, Gong, Ozric Tentacles, etc.) were doing. When I was 16, on a holiday in Florida, I bought both Terry Riley's "In C" and Pierre Henri's "Variations for a Door and a Sigh" at a record shop; both of those records were real revelations… the 90's weren't so long ago, but coming across new music then was very different than it is today.

So, I started at Northwestern University with the idea that I'd be an orchestral double bassist or something like that. That's where I eventually met Michael Pisaro (he was teaching there at the time - I was there from '97 to '01, but Michael left in 2000 or something) and Amnon Wolman, who were both really encouraging about me doing crazy things, and introduced me to this entire universe that I'd only had glimpses of before. I remember a distinct turning point, where I was performing in a Mahler symphony. It was - like most Mahler bass parts - really difficult, and we'd spent ages getting it together. Within a split second, I thought "this is great, we're nailing this," and then directly after, "I'm great at playing music that I hate." (I think Mahler is really dreadful). So, that was the end of that. By that time, I was in Michael's experimental music workshop, and I knew that doing George Brecht pieces and things (this was the same time I met Manfred Werder, and then Antoine Beuger - probably '99) was just a million times more rewarding than playing in an orchestra (now, I really love orchestras again, but wouldn't want to be in one as a player). So, I was just in the right place at the right time. Amnon asked me to premiere Michael Maierhoff's double bass piece the next year, and the year after that I did Antoine Beuger's and some of Pisaro's stuff… it's not that I was the best bass player, but I was just someone keen enough to take it on and take it seriously. Doing that Maierhoff bass piece was really great, because I remember the night of that gig on a festival as my sort of induction into a sort of experimental music culture/milieu. I'd done that piece (which Maierhoff was there to help me prepare), Michael Pisaro had done a piece by Kunsu Shim (which resulted in another guitarist shouting at him in the lobby), and Anton Lukoszevieze and Clemens Merkel both played solo programs. Then we went to Amnon's house for dinner and loads of gin and tonic. So, it all comes back around - now Anton's done a disc of my music, and I couldn't be more pleased.

Anyway, I'm leaving loads out, but that's what happened before I went to CalArts. I specifically went there for Michael and Jim, though it was my colleagues who made the place really worthwhile. I hadn't known Jim before, but I'd seen his string quintet all the way back in high school when I was looking for pieces for my quintet, and that got me into his music. More than any other teacher, I can say specific things that Jim taught me, though we didn't really work together that much. I think I got more of a general attitude about music from Michael; I shouldn't discount my other teachers, and since I can mention them, I will: M. William Karlins had a brilliant mind and a love of music that few others have, and Alan Stout (he was also one of Michael's teachers) is just a pure genius. Most of what I know about orchestration I learned from playing in orchestras, but the rest I learned from him. He claims to hold the copyright on the key of D in the UK, so watch out what you release that might be in that key (I've paid him 8 quid in advance). Then, everyone at CalArts was great, but especially Lucky Mosko - he was a treasure, and a true friend. He said that after decades of teaching, I was the first person to say that George Brecht was my favourite composer, and that made him like me.

Well, after that I was in the UK, and we met, so you know the story of the past 8 years or whatever it's been. I do still make pop music, by the way. It's just that the focus has been reversed about which one gets more attention. I just bought a 1956 Gibson electric guitar that I really enjoy playing songs on, though I like the new kitten I got for my mom even more.

The pieces on your CD are mostly – though not all – text scores. My general hesitation about text scores is that it’s kind of too easy to produce scores that are open to the point of being loose, and which don’t give the musicians enough to create music that feels unique or tied in any discernible way to the written text. But you seem to have thought these things through and have produced a number of scores which evidently work well in the right hands. Was it George Brecht that first drew you to text scores, and what is your thinking on them now?

Hmm… Well, first of all, I don't like the term "text score." I just see text as one of many types of notation that a composer can use on/in a score to lead performers to make a realization of a piece. It's really a very small number of scores that involve no text at all; usually, at least a title is text. I find that text as a notation is generally far less loose than other types of notation. With staff notation, there's this tradition that goes back hundreds of years, but it's a tradition that embraces - at most times - a tremendous looseness. Text can be far more specific than that notation ever can be. For instance, with text, I can just write, "for the length of a breath or bow stroke." There's no way to do that with staff notation, without also adding text to it.

Though text is used as notation in both "tender" and "beauty and industry," they're completely different sorts of scores. One (beauty and industry) is almost completely prescriptive, while the other (tender) is a sort of mystery; it simply sets up a situation by virtue of its existence. The performer has to interact with the score for "tender" to be able to play the piece, whereas anyone can just be told how to play "beauty and industry" without ever having seen the score. So, while the notation seems similar on the surface, it's used to very different ends. I really don't think there's any other kind of notation that provides that same breadth of possibility, which is probably why I use text so much. I just love notation - everything to do with it - in general (it was the focus of my PhD), and as it seems to me that text is the type of notation which offers the greatest number of uses, I just use it more. I mean, it's just practical. Of course there are also all of these "non-musical" (which are actually inherently musical) sorts of political concerns that lead me to it as well… I mean, you can read one of my scores and know what's going on; what the piece is. Can you do that with Sciarrino or Schnittke?

I honestly don't remember the first time I encountered text as notation. It could have been George Brecht, or maybe Wolff, Cage, Tenney, or any other number of composers. I never met Cage or Brecht, but I've been lucky enough to spend lots of time with both Tenney and Wolff. One of the important things that Tenney ingrained in me was that one should know what a piece is before making the score and working on the notation; there should be a sort of (at least mental) check-list to see that the score and notation conform to the piece. Since I perform a lot, it's easy for me to relate to how others will react to my notation. Christian has also been very helpful with this stuff; he's given me great critiques about my notation the few times I've had the pleasure to corner him about it.

I still make mistakes. There are lots of my scores which I look back on and think "Oh, I could have worded this better, or I could have changed the order these things appear in," etc., but I also think these things are a product of their time, so I don't do much revision once a piece has been played.

Anyway, it's nice that you say "in the right hands," because that's what it all comes down to. With the pieces on this CD (it's a little bit - but not a lot - different with orchestra music and things like that), I'm just one very small part of the music that someone hears. I'm an ok performer, but not a great performer. On here, you've got great performers. The composer shouldn't be the authority about what a pieceis, but just an authority; the performer(s) may have insight that the composer hasn't. I mean, this can't all just be for my ego, can it? Certainly, everyone else is getting something from it; I just can't see what that is… and thank God, because I've got my plate full just doing my little part. Really, this is why I think we make music; it's a type of communication/culture/community that couldn't exist in any other way.

So what about the conventionally notated pieces – ‘21st century music’ and ‘dulcimer’? Does it feel less exciting to compose less open works like these, or do you enjoy that as well? Can you explain how they both came about?

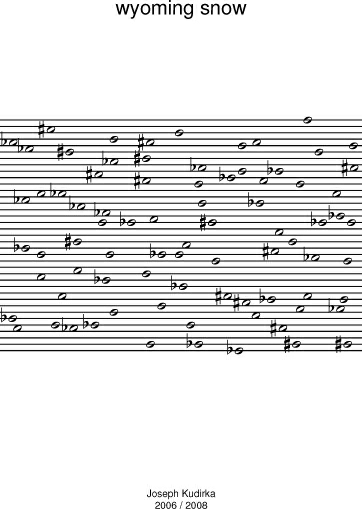

Oh, no, it's not less exciting at all. In most cases, I'm thinking about what the piece is in essence before I even consider how I'm going to notate it. There are exceptions, like “tender” and “wyoming snow” (which is a sort of adapted/extended staff notation), where the notation and a specific performer's response to it is inherent to the identity of the piece. I suppose one could say that about most staff notation too though... staff notation isn't less open, unless the composer makes it less open. You only have to listen to the different versions of Bach's “Goldberg Variations” that Glenn Gould made to see how incredibly open that notation can be in the hands of the same performer. That 1981 recording he made is really incredible; just think, the instrument he was playing on wasn't invented (pianos existed, but they weren't like the pianos we have now) when Bach wrote that, and recording technology was hundreds of years away. Yet, here is that piece, played by a performer who only has contact with that score, and he's making a version which will only ever exist as a recording. That's real openness. I can only hope that I ever make a score as open as that.

As for the two pieces of mine on this disc that you mentioned, I can tell you exactly how they came about. The pitches in “Dulcimer” are derived from a specific dulcimer I inherited from an aunt, Elma Wilson (she was a folk musician – somewhere between hobbyist and semi-pro, I guess you'd say these days – who died quite suddenly at a relatively young age, and I wound up with loads of her instruments). Well... maybe “exactly” was an exaggeration, because it's been awhile, but it was somehow a transcription of different chords that could be made on that dulcimer by fretting notes and plucking on either side of a particular fretted note in some systematic way. I'm pretty sure the three different timbres called for in the piece relate to the three courses of string on a mountain dulcimer. I could have made it into a piece to be played on any dulcimer, but as an homage to my aunt, I made a piece specifically derived from that dulcimer, which could then be played by anyone on any instrument(s).

As for “21st Century Music,” that's a dedication to Laurence Crane, whose music I like a lot (I like him a lot personally too). He's got that great piano piece “20th Century Music,” so I just thought a piece dedicated to him, written a few years later, could be called “21st Century Music.” I've done several pieces dedicated to other composers, where, when composing, I think to myself, “what is something I wouldn't write if it weren't for exposure to this person's work?” I've done works like that for James Tenney, Michael Pisaro, Lucky Mosko, Jürg Frey, Mark So, Christian Wolff... others, I'm sure – you don't need a complete list. Anyway, I was thinking of Laurence's music. His music so often relies on specific pitches and rhythms that using pitches and rhythms was a pretty natural outcome of that thought process. I wasn't trying to make music like his though – I don't think anyone could. I was just trying to highlight the small part of my own music-making that is indebted to my encounters with his work.

The pieces on your CD are dated from between 2005 and 2011, which must be roughly the time when you were doing your PhD in Huddersfield. Can you describe some of your most recent projects since you left the UK? Where are you based now, and do you make any sort of living from music?

I think about half of these pieces are from my time in Huddersfield, which was 2007 - 2012. A funny thing about doing the PhD for me is that I was busy doing all of this academic stuff and actually was writing less music than before. That said, since leaving, I'm writing less still, but what I am doing is probably more focused. In 2013 I started an ongoing project which consists of me making hand-made sheets of paper variously interpreted by myself and others (that is, it can be realized as a concert piece, set up as an installation, or just exist to be interacted with privately by individuals). I make these scores from the detritus of daily life when I'm on artist residencies; I've made pages in Winterthur and Nairs, Switzerland, and Brussels. Last year, I also started making music boxes, by repurposing parts from old Swiss music boxes to make one-of-a-kind objects which play unique tunes (like the paper, these can be set up in installations or just exist individually). Last year, I put on my first opera, which was at Université Paris 8 as part of a larger project focusing on the centenary of WWI; that was a great, new experience. So, I'm doing these things on residencies and stuff, but I'm also making a few other pieces when asked, or when the fancy strikes me. I just had a string trio done that I was asked to write for a project in Switzerland to go on a program with pieces by Beat Keller and Tom Johnson - that was nice… I did a piece for Amnon Wolman's birthday… not a huge number of pieces, but hugely variable, and generally larger in scope than what's on this CD.

I've basically been living out of a suitcase for the last 3+ years. I spend a few months a year in my home state of Michigan, working blue collar sorts of jobs (cook, bartender, warehouse worker, etc.) just because it's next-to-impossible to make a living as a composer and performer of experimental music. I do make some portion of my living from music, but it's usually not as much as from other jobs; the Swiss pay well, but it's also very expensive there. I enjoy doing residencies and things, but most are on shoestring budgets and can't afford to pay much, and the people who want to perform my stuff don't have loads of money for commissions and things. Somehow it's working; my work's getting played a lot (at least in Europe - I haven't performed in the US in 9 years, I think) which is more important to me than getting money for something that's only going to get played once by some "name" ensemble. Right now, I'm in Michigan, having worked for the summer, and getting ready to go back to Europe for the winter to do music things, though not for anything specific… Are there still flaneurs? I'm like a flaneur with a passport.

at89 Joseph Kudirka - Beauty and Industry and other pieces Played by Apartment House

‘tender’ (2008), ‘Beauty and Industry’ (2007), ‘Two Sections’ (2011), ‘21st Century Music’ (2008),

‘Wyoming Snow’ (2008), ‘an orchestral fantasy’ (2006), ‘grey’ (2005) & ‘dulcimer’ (2006)

Bridget Carey (viola), Simon Limbrick (percussion), Anton Lukoszevieze (cello), Nancy Ruffer (flutes),

Philip Thomas (piano) and Kerry Yong (chamber organ)

Youtube extract 1 - Beauty and Industry Youtube extract 2 - 21st Century Music

The score of ‘wyoming snow’ by Joseph Kudirka

To see the scores of all the pieces on the CD, go here

Joseph Kudirka Scores

You can see the scores of all the pieces on the CD here

Joseph Kudirka

Reviews

“This album opens with the 53-second Tender: sweet, husky, tentative sounds circling in space like a mobile. Later, there is Tender (Second Version) – just 47 seconds this time, but now with more tremble and more pain. Michigan-born experimental composer Joseph Kudirka uses simple terms to say significant things. His music is considered; he doesn’t shout or clutter the edges or overfill the gaps. The piece 21st Century Music is a slow and starkly beautiful cycle of downward shifting intervals; Wyoming Snow was inspired by a drive through a wintry landscape; and Beauty and Industry alternates between soft-hewn gestures against clangy, dark ones. The scores leave much to interpretation. There are two or three versions of several pieces on this disc, each one an insight into the astutely calibrated textures made by Apartment House.”

Kate Molleson, The Guardian

“Joseph Kudirka is a Michigan-born composer who studied at Northwestern University—where he met Michael Pisaro who was teaching there at the time—before following Pisaro to California Institute of the Arts, and then crossing the Atlantic to study for his PhD at Huddersfield University. Prior to composing, Kudirka's own musical history was as a bassist in local youth orchestras and bands. This album consists of recordings of eight Kudirka compositions dating from the years 2005 to 2011. They are exquisitely played by the ensemble Apartment House and were mainly recorded in April 2015, with one dating from June 2012.

While only eight compositions are played, the album consists of fourteen tracks because four of the compositions are played only once, two others appear in two versions and two others in three versions. Very helpfully, Another Timbre has posted online copies of Kudirka's scores for the eight pieces. In conjunction with the recorded versions, they make fascinating reading. They vary from the "text score" (a term Kudirka says he dislikes) of "Tender," which seems to be a dictionary definition of the title word, through to the completely notated "21st Century Music" or "Dulcimer." But whatever the format, the overwhelming impression they create is of simplicity, with choice and control being given to the musicians.

The inclusion of those multiple versions was inspired; despite their differences, subtle or otherwise, they help build up a Rashomon-style view that is more detailed and rich than any one version alone could supply. So, although its score gives no directions to players, the two versions of "Tender," recorded on the same day, by the same six players, end up being remarkably similar in mood and duration—fifty-three and forty-seven seconds, respectively. (Maybe that was the result of the musicians having discussions between the two recordings, rather than telepathy on their part?) In contrast, "Wyoming Snow," which is notated across thirty-seven stave lines, is given two very different readings by two different groups of players, the one from 2012 lasting eight-and-a-half minutes, the other from 2015 just topping six minutes. Despite their different lengths and instrumentations, those two versions generate very similar moods, evolving slowly with sustained tones which build rich soundscapes that are soothing and tranquil, without any shocks, surprises or unnecessary embellishment.

Across its fourteen tracks, lasting some fifty-three minutes altogether, the album builds up a consistent picture of Kudirka's music that seems at odds with the diverse formats of his scores. His music is serious, simple and spacious. As so often in recent years, Another Timbre has shone the spotlight on a remarkable composer, one who will be worthy of attention for decades.”

John Eyles, All About Jazz

“Other than hearing a performance of his piece wyoming snow on the radio last year, I really knew nothing about Joseph Kudirka before receiving this new CD in the mail.

That performance of wyoming snow was for multitracked cello, played by Anton Lukoszevieze. The same piece appears twice again on the Beauty and Industry CD, but played by different ensembles. Lukoszevieze is the founder of the ensemble Apartment House, which has done so much lately to present new and neglected music. This disc dedicated to Kudirka’s music is probably the latest.

As previously implied, Kudirka writes pieces open to interpretation and several of them are played two or three times during the course of the disc. An informative interview on the Another Timbre site reveals that, although his scores are typically “open”, Kudirka is leery of the term “text score” and his musical education was grounded in playing an instrument before composition became a major concern. (“I’m great at playing music that I hate.”) He’s another one of the generation of composers taught by James Tenney and Michael Pisaro at CalArts, although he did not appear on the rather wonderful and surprising West Coast Soundings album I reviewed in 2014.

The scores for the pieces played here range from introspective variations on George Brecht’s terse Fluxus scores, to general instructions determining the form, structure and materials for the piece, to music notation that leaves unspoken questions of interpretation, instrumentation and intonation. They can also be seen on the Another Timbre web site, with audio excerpts.

The music reflects Kudirka’s background as a performer. The text scores allow a music structure and character to emerge through the musicians’ choices. In that respect they ingeniously operate in a manner similar to early Feldman or late Cage, but in a looser and more generalised way. It can’t be entirely a coincidence that this music shares a similarly slow and soft atmosphere.

When I think of other text scores (good ones) they seem to concentrate on setting into motion an overall process governed by a set of conditions, either internal like Aus den sieben Tagen or external, like Cardew’s Paragraph 7 or pieces by James Saunders. Kudirka’s seem unusual in that they focus on defining and arranging details. There’s an elegance to their simplicity, and the music emerges fully defined and subtle. The repeated takes on this disc shows that each piece has depth beyond an interest in compositional technique.

Repeated listenings reveal an unexpected variety. It’s a nicely-balanced selection of works: 14 tracks in a little over 50 minutes. Enough to be absorbed by without getting entirely lost. Some pieces are barely 30 seconds; the longest reaches beyond 8 minutes. The small scale allows attention to details and gestures. Pieces like Grey and an orchestral fantasy have a sombre formality compared to the sustained tones of Beauty and Industry or the more polychromatic wyoming snow.

A large part of this is down to Apartment House musicians, who play with great sensitivity and fidelity to the score. On each track they present interpretations which are distinctive without needing to resort to extremes, setting a consistent mood that still shifts in shading from one piece to the next.”

Ben Harper, Boring Like a Drill

“Michigan-born Kudirka says significant things in simple terms. His music is considered and spacious; he doesn’t shout or clutter the edges or overfill the gaps. The piece in this collection that first caught my ear and wouldn’t let go is 21st Century Music, just a slow cycle of shifting intervals played by Apartment House with unfussy, unhurried grace.”

Kate Molleson, Discs of the Year, Daily Record

“Edgar Varese once said that “The modern day composer refuses to die,” and while it’s an inspirational expression of defiance in the face of a cultural that is bound to grind you down, it also seems a bit negative. The peripatetic Joseph Kurdika lives in circumstances that some might lament; he bounces around Europe going from one shoestring presentation opportunity to the next, and despite holding a PhD, when he heads back to his home state of Michigan he tends bar or moves stock to make ends meet. But if you look at what he’s actually doing, it seems like he is quite engaged in living out his raison d’être. He plays bass, he makes one-of-a-kind music boxes out of older music box parts, and he composes music that is at once poetically open and ultra-specific.

It is also, despite its sometimes-radical methodology, quite approachable. The six-piece English New Music ensemble Apartment House finds in Kurdika’s text-based and staff-notated scores instigations to make sounds that are gently enigmatic, yet beautiful enough to bring home to mom. “Tender,” which is the first of several that appear more than once on this CD, is a witticism — it will take most people longer to read Kurdika’s score than it takes to play the piece. But it’s also entirely on target in the way its words coax a scrap of sound from the sextet that is entirely deserving of the name. The timbres of “Grey” are as soft to the touch as a housecat’s coat, but it still exercises minimal material in a way that is non-obvious, surprising and absorbing.

Turns out that Kudirka is a lapsed orchestral musician. The same epiphany that steered him away from that career — that to do so would be to get really good at playing music he couldn’t stand — informs these pieces. By issuing invitations to not only make singular sounds, but have a bit of fun while doing so, they are gifts to the musicians who play them.”

Bill Meyer, Dusted in Exile

“

I have always enjoyed Another Timbre's practice of putting interviews with composers and/or performers on the page of each new release. These question and answer sessions are invaluable documents, placing the music and its creation in multiple and illuminating contexts. In the interview for this release, bassist and composer Joseph Kudirka emerges as a kind of troubadour of "experimental" music, traveling vast distances on both the physical and philosophical plains. Studying trans-geographically, his compositions are grounded in similarly diverse traditions springing from his work in orchestras and in smaller and more radical groups of varied instrumentation and intent. Kudirka's obvious interest in the elasticity of music and its creation is given practical voice on this disc, as many of the pieces are presented by the excellent ensemble Apartment House, in two or even three versions.

Take, for example, the title composition, presented in three versions of nearly identical timing. The sustained tones associated with Wandelweiser music are certainly a factor in all three renditions, but fluidity of timbre and attack ensure very different but equally immersive listening experiences, sustain ultimately being the only common factor. The two versions of "Tender" travel along somewhat similar lines, but there is a post-Webernian feel to the aphoristic structure that seems to generate more relative speed as one sound moves to the next.

Of the pieces offered in only one version, "21st Century Music" may be the most shocking, not because of any radical compositional method but because of the traditional harmonies that sound so naked as one morphs into the other. It doesn't seem possible that an A-minor chord can sound as shocking as it does here. Time itself seems to melt away, as there is something irresistibly Renaissance about the harmonies and the way they move and repeat, ignoring the tritons of course!

This is music remarkably free of dogma and yet willing to be beholden to a tradition if warranted by the pieces' construction. Kudirka makes the point that the pieces work best in good hands, which they certainly are; it would be difficult to imagine the music emerging with greater focus and attention to each detail than it does here. As with many discs on this excellent label, the recording is superb, letting each interval, overtone and articulation speak for itself. Flexibility of score and performance combine to make this an excellent addition to Another Timbre's large catalog of new chamber music.”

Marc Medwin, Squid’s Ear

Discount price £5