Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

at160 Kraig Grady ‘MONUMENT OF DIAMONDS’

MONUMENT OF DIAMONDS (2020) 42’

Kris Tiner - trumpets

Subhraag Singh - saxophones

Emmett Kim Narushima - trombones

Terumi Narushima - organ

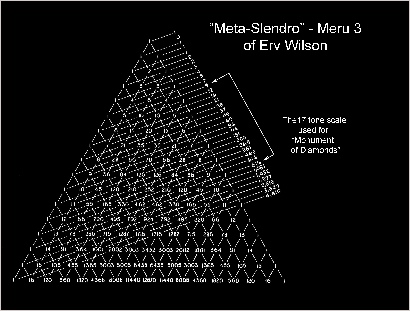

The piece uses a 17-tone version of the meta-Slendro tuning system,

created by Erv Wilson.

Interview with Kraig Grady

Could you tell us where you're from, where you live, and how you came to experimental

music?

I am originally from Los Angeles where I lived for 55 years. I imagine LA is

as much a part of my being as Dublin was to James Joyce. Truly my musical life has

been totally shaped by elements and changes unique to that city. By 16, I knew I

wanted to be a composer, even if my vision of what a composer was, and how I have

lived it is not how most understand it. This was the 1960s when the wave of psychedelic

music was sweeping the West Coast. I spent three months around Haight Ashbury as

a runaway that left me in a state of malnutrition. I miraculously recovered, only

to realise what a force music had upon me as a vision forward.

By 1970, I was going to Los Angeles City College where I was first exposed to experimental music by the physics teacher Walter O'Connell. Walter was also an artist and composer himself who had had an article published in Stockhausen's Die Reihe and had been La Monte Young’s physics teacher there also, even though he said they never discussed tuning. Some years later in 1975, O' Connell introduced me to microtonal tuning theorist Erv Wilson. This was around the same time I saw Harry Partch's US Highball and I was struck by his direction which I thought had great potential that had not been fully explored.

At this point, I began my first endeavours into microtonal tunings. There was absolutely no acceptance of it at the time, especially in the classical world so I found myself playing in punk clubs during the 1980s. There was a lot of musical experimentation in the LA punk scene that nowadays people would not call punk, but it was totally part of it at the time. I was making a living in Hollywood as a scenic artist for films and TV so having to develop these skills in the visual medium, I began working with silent films with live music. This lasted a decade before I started working with shadow plays. All the while I kept building instruments and writing music for myself and anyone else who was willing to play them. This developed into a strange type of musical life as somehow, I became recognised outside of the club world as well. For example, one week I might have a gallery show with electronic composer Morton Subotnick and vocalist Joan La Barbara, then the next week I would be opening for punk band the Minutemen; an invitation to perform at art patron Betty Freeman's home alongside Mauricio Kagel might be followed a few days later with a punk rock show with The Fibonaccis.

While my work was well received in Los Angeles, the size of my instruments made it difficult to present my work outside the area. Other than the occasional show in San Francisco and a three-month arts residency in France, my work remained in Los Angeles. In 2007, however, I left LA and moved to Wollongong, Australia to marry Terumi Narushima, a fellow microtonal composer.

I guess that the experimental music scene in Wollongong is a little different from LA. How is it there, and has the adjustment been difficult?

Pretty much my musical life here has centred around playing in a duo called Clocks and Clouds with my wife, Terumi. Sometimes we are joined by others but for the most part I play Meta-Slendro vibraphone (clocks) and Terumi plays the Meta-Slendro organ (clouds). It is indeed a giant change from my life in LA where I lived for over a half century. It means fewer shows but my quality of life is better and thus leads to a different music. Nature is a much stronger presence here and I believe is a stronger element in my music. There are way more stars, and constellations I have known since a child are all of a sudden upside down. That was a shock at first. Despite its limitations, I am grateful that I am not living in the US at the moment, but I am admittedly all too emotionally tied and upset by conditions there.

Moving on to 'MONUMENT OF DIAMONDS', it uses a rare tuning system - Erv Wilson's

17-tone Meta-Slendro tuning. Why did you want to work with this particular system,

had you used it before, and do all your pieces involve unusual tunings?

My entire

musical life since 1975 has been working with alternative tunings. This piece represents

the fourth of a series of works in which I ask each performer to play and record

individual notes of a particular scale by matching their pitch against a tuner. These

recordings become the raw material from which I construct the composition, note by

note, through a painstaking process which in this case took two years to complete.

Each piece in the series has been in a different tuning. For MONUMENT OF DIAMONDS,

the 17-tone Meta-Slendro tuning is an extension of the one around which I have built

an ensemble of instruments. With the exception of a 37-tone instrument, this ensemble

consists mainly of instruments with only 12 pitches per octave, but none of these

pitches are found in standard 12-tone equal temperament. Slowly, I have been adding

five extra tones to each instrument to make a 17-tone scale. So, in a sense this

composition is exploring an area I am planning to be using on my instruments in the

future in live musical performances. Doing compositions for the recorded medium has

enabled my music to be presented to people who cannot experience my live shows. I

am extremely grateful that Another Timbre is helping that happen.

So did you really construct the whole piece note by note in this way, without playing any sequences of notes at all?

Yes, the players were engaged in the act of playing meditations on single notes. This created a quality all its own where their focus is on timbre and stillness in terms of pitch fluctuation. Each performer determines the duration of the notes they play, and when I add these notes into my composition, it is this duration that I first hear and more often than not preserve.

Are the listed instruments (organ, trumpet, saxophone, trombone) regular instruments, or ones which you have adapted or built yourself to better fit the Meta-Slendro tuning system?

The instruments I use in live performance are instruments that I have built or modified myself to fit the Meta-Slendro tuning. These include various mallet percussion instruments, harmonium, and string instruments. For this recording, however, the trumpet and trombone are regular instruments and the Infinitone saxophone is the invention of the performer, Subhraag Singh. These are all acoustic instruments played by real people and I feel that the individuals offer something that if played by someone else would lead to a different outcome. The exception is the organ which is electronic, and it is used only in the last section of the piece. Each gesture that the players produce on a single tone is reproduced exactly every time the note occurs in the piece. My own experience is I become acutely aware of what each player does and does uniquely. I had plans to include some of my own Meta-Slendro instruments in the composition but there never seemed to be the right point to introduce them without sounding forced.

As a non-musician, I can hear that there are some unusual intervals in the piece, and I enjoy the sense of displacement this brings, but I’d never be able to identify what system is being used, or what is going on in any detail. How important is the particular system to you? Western tonal music sometimes allows itself a little bit of atonality. When you are using the Meta-Slendro tuning, do you allow yourself to deviate at all from the system?

In my music, the tuning I would say is as important as the tuning of a raga where each pitch is also thought to have an emotional quality. Rather than expressing emotions, it seems that music has the potential to create emotions that happen nowhere else. It makes certain emotions possible. This is what I believe.

Another important aspect of a tuning system which is rarely discussed is the structural possibilities it offers. The Ancient Greeks saw them as a reflection of cosmology and their political ideas were meant to be in tune with the music of the spheres. The mere act of modulating was seen as a crisis.

The Meta-Slendro scale used here is one that shares features of many African and South-East Asian scales. While the Western scale has intervals that tend to sound either consonant or dissonant, here each note has relatively the same degree of consonance, or mild roughness. This allows for its own type of possibility, its own ‘anarchic harmony’ but without the ambiguity. The notes of the tuning I use have been calculated to very precise frequencies based on mathematical structures and relationships, so I expect a high degree of accuracy. I have no desire to deviate from this tuning system because the system itself offers so many unique acoustical possibilities.

Someone once said that the difference between Western and Eastern art was that the West is always searching beyond its confines while the East is concerned with going deeper into what is already there. The aforementioned ragas are good examples of this going deeper into the image of the raga. Many decades ago, when I abandoned the Western scale, I took one big step outside of the tradition, but have since approached these new scales with a dedicated focus, reaching into their depths.

To my ears the music retains a meditative quality even when it becomes quite dense – which is similar to Indian ragas in that even when Indian classical musicians are playing extremely fast, the music still feels relaxing rather than busy or frantic. Is this a quality that you are seeking in your music, and is it partly what has drawn you to the Meta-Slendro tuning system?

I quite appreciate that. I enjoy that quality about Indian music and also how that music continues to evolve and develop both rhythmically and melodically. Their musicians exhibit some of the finest ears in terms of pitch I have witnessed. I try though to keep a good distance from their use of drones or their scales but do relate to their sense of time and the importance of pitch organisation. The Meta-Slendro scale is one of many scales that offers a less dissonant sound world than one experiences with the Western scale, yet still offers new relations to explore. One does not have to be harsh to explore new things. The actual activity of composing is something interactive and feels like it is a force that works with me as opposed to against or neutral. It is only one of many scales with similar momentum, some of which I have explored in other pieces.

Can you tell us about the title? What does it refer to?

The idea of Monuments came from the sound of the brass, in which I include the saxophone here. Brass seems to be used much less in newer music than strings, winds and percussion which is unfortunate. Since they are used less than strings or winds in new music, they seem to invite exploration. Working with these instruments invoked sensations of large spaces, forces of gravity, crystalline solidity, and the aeons of time. Here I had exceptionally talented players to work with. As I have always associated music with ‘space’ and places like Anaphoria Island, this piece evokes an environment of monuments, ruins that still house some souls within their buried histories. Diamonds reflect the treasures of earth, but there is also the tuning structure Harry Partch used in this case. I have never been attracted to his tuning, but somehow in the course of the piece, I unexpectedly found myself working with small diamond-like structures, so there is a play on words.

Kraig Grady

Cover painting by Fred Tomaselli