Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

at70 John Lely - ‘The Harmonics of Real Strings’ (2006/2013)

played by Anton Lukoszevieze, cello

4 realisations, one on each string of the cello

1. 16:42 2. 15:57 3. 12:08 4. 11:08

Recorded in Norwich, February 2014

CD copies sold out, but downloads still available from our Bandcamp page here

Interview with John Lely

'The Harmonics of Real Strings' is one of those simple but brilliant ideas. Can you explain the concept in your own words, and where do you think the idea for the piece came from?

Essentially it’s a very slow glissando along the full length of one bowed string. The player uses light finger pressure on the string – what is traditionally referred to as ‘harmonic’ pressure. There are a few other details, but that’s the gist of it. I think the title is a bit of a red herring – I hear a broad range of sounds emanating from the instrument, not just ‘harmonics’.

Around the time I wrote the piece I was having trouble sleeping. I would lie awake listening to short-wave radio, scanning through the frequency spectrum, turning the dial in one direction as slowly and consistently as possible. I found myself listening to the process, appreciating the variety of sounds that emerged from the loudspeaker – sounds of gradual transition, sounds as by-products.

I had also been experimenting with very long music strings for some time. A string can have many strange and wonderful characteristics, some predictable, others less so, depending on how it is activated.

So, those were some of the ideas floating around in the background, but I think of them more as aspects of technique that were not really at the front of my mind when I thought of the piece.

You talk about 'experimenting with very long music strings', and your music often has the sense of being 'experimental' in a literal, almost scientific sense. Could you tell us a bit about your background and your work in 'experimental music'?

Actually it was what people call ‘experimental music’ that made me want to study music in the first place. When I was a teenager I used to listen to late night radio – John Peel and BBC Radio 3. That’s where I first got to know the music of Morton Feldman and John Cage, and other American and British experimental composers. Around that time I also found Michael Nyman’s ‘Experimental Music’ book in Norwich library, and I tried playing scores from that with a couple of school friends. So ‘experimental music’ was my starting point for broader listening, and eventually composing. When I moved to London in 1997, I gradually met more like-minded people, and I started putting on concerts and improvising.

When I’m composing I’m learning, asking questions and testing limits. I appreciate the effect of compositional constraints because they reveal something new, either about the material or about myself. Whatever my material — a long string, a harmony, a silence — I try to put on hold any preconceptions I might have. My focus is on understanding and coming to terms with that material through careful listening. Maybe that’s where the ‘experimental’ comes in for me now.

I take a workshop attitude – learning by trying. I’ve explored many different forms of music-making over the years. I follow my curiosity. For instance, I’ve recently spent time visiting the French Cathedrals where polyphonic music first emerged – reverberant spaces which seem to encourage certain ways of singing and listening. Actually, through just being in those spaces and listening to their acoustics I’ve felt a deeper appreciation for the work of twelfth century composers such as Perotin and Leonin. They were experimenting too.

You talk about ‘appreciating the effect of compositional constraints’, but I first came across you back in 2000 on an improvisation CD with Seymour Wright and Yann Charaoui. It was released on Eddie Prevost’s Matchless label, and at that time you were evidently also involved in improvisation through the weekly workshop that Eddie runs in South London. Is improvisation less of a focus for you now, and if so, why?

I actively pursued improvisation as a practice for a number of years because it enriched my experience of music. Now I find myself thinking more about things that can be written down. My current priorities lie in exploring relational aspects of music such as series, proportion, correspondences between elements, harmony, and what could loosely be called voice leading. Improvisation can at any moment intersect with any of these things, but its inherent unpredictability makes it less relevant to my current work than it once was.

More broadly though, I’m always on stand-by for those special moments in music that excite my imagination. In that sense I don’t really differentiate between practices such as composition and improvisation – a piece of music can be based in any number of practices. What I care about is that special arresting quality, when my mind is carried by the music.

I think that’s well put. Two years ago you and James Saunders published ‘Word Events’, which was a kind of critical anthology of text scores, or verbal notation in contemporary music. Could you talk a bit about what has drawn you towards text scores, and is it the principal area that you now work in?

I was probably first made aware of text scores through Nyman’s book, and I remember it was Michael Parsons’ Walk that really grabbed my attention. Another inspiration was Sol LeWitt’s instructions for his wall drawings – I was very pleased that we were able to include his Wall Drawing #960 in ‘Word Events’.

For me verbal notation offers a good way to explore the limits of an idea, to get down to essentials. When staff notation falls short, words can be very effective for describing aspects like process, intention, effort, and the general conditions of a piece.

In the case of the first performance of ‘The Harmonics of Real Strings’, I didn’t show Anton a score – I simply spoke with him about the performance beforehand. Gradually, through dialogue with Anton and other string players, I developed a written text that explains the process and answers the most frequently asked questions. Over the years I have talked the piece over with various musicians from quite different musical backgrounds, and I’ve been able to refine the language of the score in light of those conversations. As with some of my other pieces, I do still sometimes explain the piece orally, but the score continues to serve as a useful point of reference.

Between around 2002 and 2009 verbal notation was usually my chosen medium, though in recent years that has changed. I’m still interested in that paired-down, essential quality, but the written word doesn’t seem to be appropriate for what I’m currently doing. My scores are now notated almost exclusively on staff paper.

Could you tell us what kind of things you are currently composing?

I’m composing harmonies, interlocking melodies, mostly for small groups of similar instruments. ‘Four Reed Organs’ was the first of these works, and I made a piece called ‘Doubles’ for the Bozzini Quartet Composers Kitchen in 2012. That experience got me back to writing for string instruments. Since then I’ve been working with the Tre Voci Cello Ensemble at nu:nord, and I made a violin and cello piece for Apartment House’s 2014 tour of Russia. I’ve also been writing for solo instruments – I recently made a long piano piece for Philip Thomas, and this autumn I’m thinking about the violin.

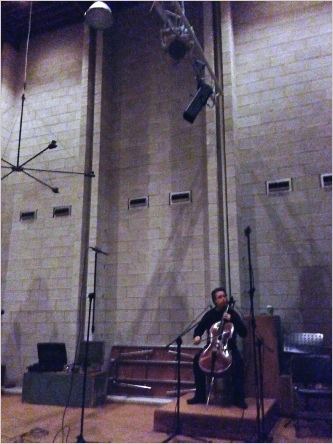

Anton Lukoszevieze recording John Lely’s ‘The Harmonics of Real Strings’

Reviews

“The Harmonics of Real Strings by composer John Lely and cellist Anton Lukoszevieze is a meditative yet adventurous expedition into the nature of the cello. It is highly experimental and process oriented, almost to the point of being a scientific experiment, yet remains easy on the ear throughout.

Technically, the piece is very simple. The cello has four strings. Each movement is simply a slow journey, from the low, open string, up through the harmonics produced by lightly pressing the strings as one bows. In other words, this piece is so minimalist, that each movement is not simply for solo cello, but for a single solo string. In this sense, the album translates the cello on a more naked and intimate level than virtually any other recording. Interestingly, exposed in this manner, the sound is surprisingly metallic in quality; not unpleasant, mind you, but somewhat machine-like. The cello is generally associated with rich, emotional timbres, but pulled away from melodic material, we are reminded of what a cello actually is: four tightly stretched steel cords.

With this composition, Lely is playing more with negative space than additive construction. Lely has taken conventional composition and ripped away all but the fundamental aspects of acoustic resonance. We hear the clear-tone of harmonic pitches, the breathy sound of the bow gliding across the strings, the thick, yet somehow empty sounds which are produced in between harmonics, and the rich echo of the room in which the piece was recorded.

You could call this album an exploration of the harmonic series on cello. The listener is given a doorway into the nature of cello, and sound itself, prior to conventional composition.

The end result is a wonderful ambient experience. It functions both as a quiet mediation, suitable as background for inward study and a probing study of the instrument. This recording is highly recommended for anyone enraptured by sound itself.”

Christopher Mandel, Squid’s Ear

“The Harmonics of Real Strings by composer John Lely and cellist Anton Lukoszevieze is a meditative yet adventurous expedition into the nature of the cello. It is highly experimental and process oriented, almost to the point of being a scientific experiment, yet remains easy on the ear throughout.

Technically, the piece is very simple. The cello has four strings. Each movement is simply a slow journey, from the low, open string, up through the harmonics produced by lightly pressing the strings as one bows. In other words, this piece is so minimalist, that each movement is not simply for solo cello, but for a single solo string. In this sense, the album translates the cello on a more naked and intimate level than virtually any other recording. Interestingly, exposed in this manner, the sound is surprisingly metallic in quality; not unpleasant, mind you, but somewhat machine-like. The cello is generally associated with rich, emotional timbres, but pulled away from melodic material, we are reminded of what a cello actually is: four tightly stretched steel cords.

With this composition, Lely is playing more with negative space than additive construction. Lely has taken conventional composition and ripped away all but the fundamental aspects of acoustic resonance. We hear the clear-tone of harmonic pitches, the breathy sound of the bow gliding across the strings, the thick, yet somehow empty sounds which are produced in between harmonics, and the rich echo of the room in which the piece was recorded.

You could call this album an exploration of the harmonic series on cello. The listener is given a doorway into the nature of cello, and sound itself, prior to conventional composition.

The end result is a wonderful ambient experience. It functions both as a quiet mediation, suitable as background for inward study and a probing study of the instrument. This recording is highly recommended for anyone enraptured by sound itself.”

Matthew Hammond

“The austerity of presentation as favoured by the Another Timbre label is doubtless intended to place emphasis wholly on the sound of the music therein, but a few words on the composer might not come amiss. Hailing from Norwich, John Lely has ploughed a productive furrow in the ‘experimental’ domain that has been central to British music throughout the post-war era. Relatively prolific and often performed, his output will be most familiar to those who frequent YouTube: The Harmonics of Real Strings has been championed by Anton Lukoszevieze over the past decade and his recording amply underlines the concept’s inwardly focused intensity.

In the words of the composer, ‘Essentially it is a very slow glissando along the full length of one bowed string. The player uses light finger pressure on the string in what is traditionally referred to as “harmonic” pressure’. Music, then, in which process is at least as crucial as its ultimate destination – though the outcome is no less considered than in similarly reductive or slow-burning pieces by such (very different!) figures as Scelsi or Feldman. Presented here are four realisations – progressively decreasing in overall duration and, revealingly, numbered in reverse order (hence from IV to I). Heard thus, the effect is of a subtly incremental increase in expressive velocity – as if the sound were gaining all the while in momentum – though the prevailing quality is of an ethereal inwardness. Lukoszevieze renders it all with the requisite understatement, heard in a close and yet atmospheric setting wholly in accord with this music.

Richard Whitehouse, The Gramophone