Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

at148 Frank Denyer ‘The Boundaries of Intimacy’

1 Mother, Child and Violin (2005) 6:02

Juliet Fraser (soprano) Layla (child vocalist) Janneke van Prooijen (violin)

2-7 Two Female Singers and Two Flutes (2013) 11:52

Juliet Fraser & Sophie Fetokaki (voices) Jos Zwaanenberg & Carlos Anez (flutes)

8 Piece for Koto version 2 (1975) 4:50

9 Piece for Koto version 1 (1975) 3:15 youtube extract 1

Nobutaka Yosjizawa, koto

10 String Quartet (2017/18) 18:23 youtube extract 2

Luna String Quartet: Janneke van Prooijen & Diamanda La Berge Dramm (violins)

Elisabeth Smalt (viola) Katharina Gross (cello)

11 Beyond the Boundaries of Intimacy (2015) 12:31

Jos Zwaanenberg (flute & electronics)

12-13 Frog (1974) 8:36 youtube extract 3

Elisabeth Smalt (sneh)

Sleevenotes by Frank Denyer

Most of the music on this CD is soft, some of it very soft indeed. To achieve the optimal listening level, think of the musicians as being just over the other side of the room in which you are listening, rather than in another grander space. Imagine them performing intimately, without amplification, and often in an under-voice in order not to disturb the neighbours. This will give you a realistic idea of the listening level. You may find it takes a few minutes to get used to it, but your ears will soon re-adjust.

Mother, Child and Violin (2005)

A musical family portrait. The woman as mother leads, the child follows, often in imitation. The violin is more remote, more abstract but its melodic span is wider. The piece is self-contained, at times playful, at others perhaps a little anxious and there are even moments of distress. All is nevertheless subsumed within its formal unifying linearity. Questions arise: is the violin the real father or just acting as a surrogate father? The child hints at playfulness but nonetheless is restrained and on her best behaviour. Is the unity between these family members their underlying strength or an unnecessary inhibition?

This is one of the four pieces I wrote with ‘woman’ in the title, but it is the only one of the set requiring more than a single performer. The others are: Woman Viola and Crow (solo violist), Woman with Jinashi Shakuhachi, and A Woman Singing (solo voice).

Two Female Voices and Two Flutes (2013)

Nestling inside this single span of music are six smaller pieces. The two singers, in addition to their vocal sounds, knock and scrape a cloth board, and fleetingly tap one of four tuned porcelain bowls. Later on a heavy wooden pole is used. The first flautist plays the standard silver flute and a bamboo flute, the second plays baroque traverso, bass flute, and piccolo.

Piece for Koto version 2 (1975)

When I began studying the koto in 1974 I was immediately attracted by the austerity and emotional restraint of the traditional repertoire. I was also interested in the traditional tablature.

All musical notations, including stave notation, specify just a few of the music’s essential ingredients, the rest is left to the oral tradition. Certain facets are thereby highlighted and given a privileged status. What exactly falls into this category is peculiar to each system but reveals a great deal about the underlying musical aesthetic of the culture which created it.

This little piece of mine started as a simple exercise to better understand traditional koto tablature and to discover how it would affect my own musical thinking if I used it as a composer. At first I found that the notation was drawing my attention to musical parameters I had previously considered ephemeral, such as the precise string to be used for a particular pitch, the exact finger to be used and whether it was to be an upstroke or downstroke. On the other hand, the notation made it next to impossible to think about absolute pitch or any fine rhythmical detail.

As I proceeded I became more acclimatised to these new circumstances, which amounted to a real shift in orientation. It gradually became clear that what I was writing was no longer a mere exercise, but was adding something essential to my compositional work.

Piece for Koto version 1 (1975)

The two versions of this piece started to develop quite early in the compositional process. Even before I knew exactly what it really was, it started branching out in two irreconcilable directions. As a composer I am familiar with this situation, but normally this soon resolves itself as one version becomes dominant while the other is eventually abandoned. However, in this case I remained very much attracted by the restraint and austerity of line in version 1 but could not bring myself to negate the many delicate techniques of version 2. Although the underlying structure remained the same, the two were irreconcilable and I continued to work on them both still half-believing that at some point an accommodation would suggest itself. This never happened and so the two versions resulted. Even now I can’t say which I prefer.

String Quartet (2017/18)

The emotional differences between a note being played by a single instrument and the same note played by two similar instruments in unison, are significant. This changes again when three instruments combine, and is different again with four. All such changes affect the music’s ‘tone of voice’. Intimacy diminishes in inverse proportion to the number of players. Even richer changes occur when octave doublings are in the mix. In this string quartet I wanted such perceptions to become a major part of the music’s dialectic, as it delicately carries its single melodic strand through time.

A central part of all my recent work has been the exploration of the under-voice and the problems of making it manifest. Aspects of playing are heard that are usually subsumed under a more sparkling surface, but beneath this surface there is another world with its own ways of articulating time. In this work all four instruments use heavy practice mutes.

Beyond the Boundaries of Intimacy (2015) for flute and electronics

Composed and dedicated to Jos Zwaanenburg, a long-time friend and colleague to whom I owe much. In this piece, the almost imperceptible use of electronics (my one and only step in this direction) is simply a friendly nod of recognition for Zwaanenburg’s ground-breaking new interfaces between flute and electronics.

For this piece, the performer does not stand back from the audience but comes as close as is practicable. No visible wires or connections connect the player, or the flute, to the sounds coming from the speakers, and neither should the flautist appear to control them. The speakers are placed far apart, invisible to the audience and preferably high up so that it is impossible for the audience to locate the source of these sounds in any particular direction. These ‘other’ sounds are all pitched and conventionally notated in the score but are so soft that they have little recognisable timbre except when they imitate the live flute (8’42” to 8’52”). The precise dynamic level of these sounds ranges between ppppppp and ppppp. This piece is unsuitable for large concert halls.

Frog (1974) for a bowed stringed instrument

Written in Ahmedabad, India, the odd title popped into my mind while composing and wouldn’t go away, although I had no idea at the time what it might mean. A week or so later I tentatively pencilled it in at the top of the page and it just seemed to belong there, so I kept it. The generic instrumental designation ‘for a bowed stringed instrument’ merely reflected my desire to keep open the doors to musicians from other cultural traditions, but it would be fair to say that at the time this was no more than an aspiration for the future.

In 1980 I designed a new bowed stringed instrument for Frog and parts of Melodies. I called it sneh. It is a bowed instrument with a skin covered belly and it has a timbre that I thought particularly suited this music. For some reason, such a family of instruments never developed in Europe, although they are quite common in other parts of the world, and so I decided to fill the gap with a design of my own. One of my first problems was finding the skin to cover the sound box. I was living in Kenya at the time, and through my fieldwork, monitor lizard skin was easily obtained. This had certain advantages over animal skin because it does not stretch with humidity and is also very long lasting. It also looks really beautiful. The new instrument was given an extended viola neck so that at least some western string players would not find the idea of learning a new instrument too daunting. A few sneh performances did take place at that time, but players found it heavy and unwieldy and it soon took up a silent residence in my study where it lived for the next 35 years. But one day it was spotted by Elisabeth Smalt, who instantly took it off the shelf and started to tune it despite the fact that it had lost one string and looked a little neglected. Immediately it sprang back to life and she decided then and there to seriously take up the challenge of mastering the instrument. Her long experience with Partch’s adapted viola was clearly a help.

For some years I referred to it as my lizard viola, but my wife asked me to name it after her sister, who sadly had died prematurely from cancer. Her name was Sneh.

Frank Denyer, August 2019

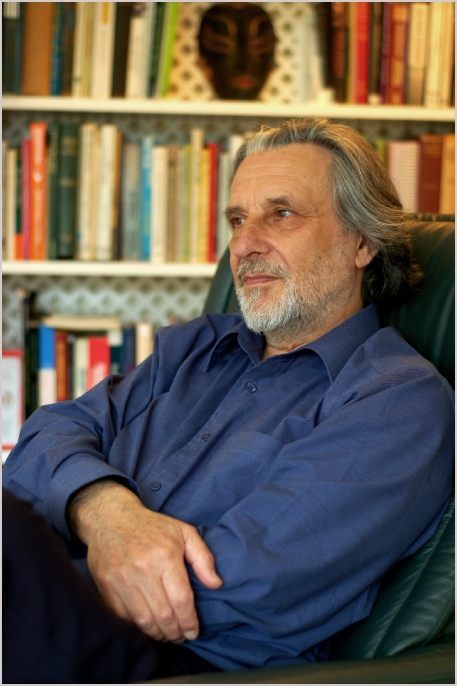

Frank Denyer

Nobutaka Yoshizawa

Elisabeth Smalt playing the sneh