Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

at83 ‘Extinguishment’ by Fraufraulein (Billy Gomberg & Anne Guthrie)

1 Convention of Moss 11.30

2 Whalebone in a treeless landscape 16:50

3 My left hand, your right hand 13:36

Billy Gomberg - bass guitar, recordings and electronics

Anne Guthrie - french horn, recordings and electronics

Recorded June to September 2014 in Bloomington, Louisville, Chicago and Brooklyn

Interview with Billy Gomberg & Anne Guthrie

Could you tell us a bit about your backgrounds? What were your early encounters with music?

BG: Growing up in Chicago my parents mostly listened to the oldies station and took us to musicals. I used my last reserve of pre-adolescent goodwill to convince them I should have a bass guitar. A few months of lessons gave me the basics, and I looked up tablature for the songs I'd like to play. Any concert my friends were going to I went as well and this started with Nine Inch Nails in 1994. I got kicked in the face. Musically & personally there were more formative concerts, but the fall season of '94 was less uncorking the bottle and more like smashing the bottle to christen the ship. A few more pedals and a four track recorder followed and then I had to have a synthesizer and that's a standard, very slippery slope.

Most of what I experienced was more left field alternative rock or industrial/gothic/ambient as both of these worlds had big footholds in Chicago in the 90s. A cousin in San Diego sent me tapes of bands he was seeing at the time. I went to a lot of concerts and DJ nights and poorly lit parties and in general had a very immediate, physical experience of music.

When I was bored or slacking on the weekends I'd walk up Clark Street and do a run through the used and specialty record shops - 2nd Hand Tunes, Reckless Records, etc. I watched a lot of movies and those also served as an introduction to a lot music I wouldn't have heard otherwise - listening to Kubrick, Lynch and Greenaway films, I didn't know what I was really hearing at the time.

My high school offered two semesters of music theory which illuminated things, made it easier to be in bands and give some of my ideas language & structure. I had a lot of ideas and a couple of tools and I knew what chords and rhythm were, eventually I found some friends outside of school who shared a lot of general aesthetics with me and we were at the same skill level so we could do sad, dark music together, and music wasn't so much a solitary practice for a few years. I was extraordinarily fortunate in the amount of freedom (not always permission) I had to explore these things at that age.

And what about closer to the present? You work with Anne a lot, but who else do you collaborate with, and do you feel yourself to be part of a wider musical movement in New York or globally?

BG: Unsurprisingly Anne is my longest and closest collaborator and we have certainly done more concentrated work in the last few years - ”Remarks on Color,” touring, local gigs, this album – than previously. Collaboratively we are in a copacetic place, the title of Extinguishment refers to and riffs on that. Our work together has developed a more defined character in how it takes some materials and approaches from our individual practices, but loosed from our larger, separate contexts, the work gets a little more space and dimension, which opens the room for something new to occur. The language we used together on tour and during the recording and assembly of Extinguishment drew heavily from our own experiences and trust together, and that is special, that is a great place to be in a live, improvised context. This is intimate and open music, not that the audience is invading our privacy, but something internal to us becomes shared experience. There are technical and material ways that this work differs from our respective solo recordings and other collaborations - we definitely enabled each other to make choices we wouldn’t have made if we were working on our own.

We’ve both worked with Richard Kamerman as Delicate Sen for many years and that always is a bit different - we are consistently sporadic. Richard and I have done a few duo projects based mostly on “let’s make _____ music and maybe fail fantastically” and those have been exploratory, fun and….rougher. Almost as important is that both Anne and I have played with a lot of other great musicians just once or twice. Neither of us are incredibly fussy about what exactly we end up playing; we do have some limits and not every collaboration is successful or satisfying. We do strongly feel the importance of the social aspect of music making and appreciation.

Many of our friends are musicians as well - Robbie Lee, who plays on “My left hand, your right hand” [one of the pieces on Extinguishment] and provided recording space for us, has been our friend for years and we haven’t played music together at all until this past year. New York has been very good to us, and so have a lot of other places in the US and overseas, but I won’t say that I feel as if I belong to any particular movement or scene. I’m not actively resisting a kind of categorization, but neither am I seeking it out. Genre can be didactic - I’m listening and I’m exploring what is happening when I am making music, live or not, if the result doesn’t end up as a 10/10 “this genre” then...whatever, that’s not important to my practice. Words like “play” and “practice” are important here. I’m going to miss something if I’m always trying to make exactly “this music” or “that music.” We were not trying to make a particular kind of music with Extinguishment.

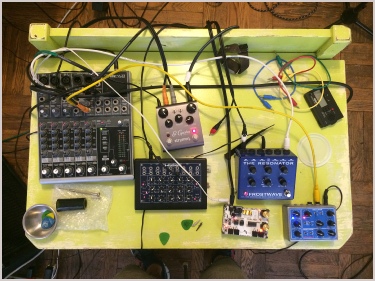

I do use different technical setups depending on whom I am playing with - the more musicians I’ve joined up with, the less I have to play! Extinguishment is probably the first album since the first Delicate Sen CD where I didn’t use a computer in any way during recording, which was very freeing (and quite intentional). This choice is a product of playing in many different scenarios, and having instruments & devices from which to select the most appropriate kit to realize my practice effectively in a given context. I’m always trying to make the same sound (more or less), but I’m always trying to evolve how I do that.

What about you, Anne? What is your musical background and training?

AG: As the bio reads, I have an undergraduate education in music performance and composition, and a PhD in architectural acoustics. I currently work as an acoustical consultant at a building design and engineering firm. Previously, I worked as the managing director for the SEM Ensemble in Brooklyn.

I wish I could say I had some magical encounter with contemporary music at an early age. My first encounters with music were pretty standard classical fare. My grandfather was a pianist, and would regale us on every visit by banging out Chopin and Beethoven until the piano had to be retuned. I remember especially enjoying the way his Hanon exercises would waft through the house for 3 hours a day. I wrote my first composition in the 6th grade, a waltz for oceanic wildlife on a Casio keyboard. I played piano and French horn from elementary school, slogging my way through band lessons and joining the youth orchestra in middle school. In high school, I entertained fantasies of a career in the philharmonic, and I became very attached to Shostakovich’s 5th Symphony when the youth symphony played it in China senior year.

All throughout this time, I was in fact surrounded by the music and sounds that I would later understand as influences, although at the time they blended into the background. My parents tried to give us full exposure to the art of weird. Fluxus exhibit at the Walker, John Cage concert at the Ordway, playing works by young composers in the youth symphony, Webern and Reich drifting in over NPR, the noisy experiments of Sonic Youth. But it wasn’t until college, exposed to the entire history of experimental music, that I began to actively seek out the artists who have influenced my work today. Meeting Billy, studying abroad in London, and taking courses in experimental music, allowed me to make sense of the sounds that had always been at the perimeter of my listening experience and understand my own creative practice in context.

Those ‘sounds at the limit of (your) listening experience’ certainly feature in every piece of music I have heard by you, from the ‘Standing Sitting’ CDr on Jez Riley French’s label onwards. Field recordings are far from being the only ‘instrument’ you use, but they occur in your music a good deal. However, you seem to use them more as a tool for composition than as a way of documenting an environment. Do you think of yourself as being primarily a composer (as against a field recordist, instrumentalist, improviser or whatever)? Or is there no hierarchy to the different aspects of your creative activities?

AG: I approach field recordings in a few ways. The first way is as an instrument or element for a compositional palette. This tends to be more on the drone end of the spectrum, something I can process to create a textured yet musical bed for other sounds. The second is as a pre-composed fragment, a module of sorts. Finding these feels like a treasure hunt, in a way, where I am seeking out a unique sonic event that is melodic but moderated by the environment (a person singing on the sidewalk, speech from a PA in a train station, mechanical resonances, clicks of mahjong tiles in a park). Because these are so recognizable, I don’t like to use them for long periods, but rather as brief events in the foreground that I place specifically. They occasionally get a lot of processing, but I do like to at some point reveal the source. In this album, for example, the hymn from a Norwegian Day festival in Manhattan is played with no processing at all. This is a very composed moment. On the other hand, a recording of beeping from a mobile heart monitoring truck outside of NYU Hospital has been processed and used to build up a melody and play harmonically in a duet with Billy’s bass guitar. The last way, of course, is to generate a neutral soundscape, to locate my composition in an imaginary geography, which I use least often, but have started to explore in collaboration on this album.

Up until a few years ago, I kept my processes fairly separated between improvisation and composition. Electronic and French horn music was pure improvisation, edited into tracks after the fact. My compositions were purely instrumental and acoustic, and heavily notated. However, on my most recent album (Codiaeum Variegatum), I composed parts for other instruments, and started to be more free with my notation. In collaboration with Billy, we wrote our first indeterminate composition, Remarks on Color, last year (links below).

Along with instrumental performances, soundscapes were created as a part of this piece. The soundscapes were played back over loudspeakers, but they were used as an instrument, played (volume, on/off control) as part of the score by the musicians. However, when the speakers were on, the material served as soundscape rather than melody. In this sense, we started to manipulate the boundary between the two in a way I really enjoyed. On this album, I think we have realized it in an even more fluid way.

http://www.experimentalmusicyearbook.com/Remarks-on-Color

https://soundcloud.com/omgindexical/billy-gomberg-anne-guthrie

Yes I think that’s a lovely piece. I’m interested in the way you use melody. In some experimental music circles melody is virtually verboten, but you have often embraced it in your work. Do you feel that you are to some extent going against the grain in this?

AG: First off, I think melody can be defined separately from harmony. I think of melody as a single voice or layer, and with multiple layers, I like them to overlap in non-structured ways. I am interested in homophony more than polyphony or harmony, where if you take a cross-section through these independent lines you might see something like texture or harmony, but it is not intentional. In a way, that cross-section is your soundscape. So where a lot of music is focused on the texture or cross-section, laying it flat and mapping out a scene, I think of my work and Fraufraulein’s work as passing through a number of views of this same scene, rotating around it or watching it at different times of day. A lot of the melodic content I have generated and used in the past comes from found elements, be they transcribed speech or heavily-processed resonances. A lot of works I discovered in college, while working on my undergraduate thesis, got me started on this path. Heiner Goebbel’s Hashirigaki, Robert Ashley’s Perfect Lives, Akira Rabelais. Some work Billy was doing at the time with answering machine messages.

I think one of the reasons melody is shunned is because there is this idea that it is programmatic, or it has to imply a narrative. But when you think about it, composers like John Cage, Christian Wolff, and Earle Brown all have these melodic fragments in their work that have an eerie absence of context that heightens the experience. And what we are doing in our work, like any kind of collage on paper, creates a somewhat arbitrary meaning by juxtaposition, but it is definitely not program music. There are no Wagnerian themes, or characters assigned to the melodies. When I use transcribed speech, for example, different instruments are playing different harmonics from the same syllable. Lines from different characters are played as a single melody by one instrument.

Now that I’m talking about this, I realize that one thing that would be really cool is to hybridize this, take the traveling melodies to a certain point in time and stop, stretch it out, move into cross-section. Suddenly melody becomes texture and stops for a while, before moving back into the chronological stream. Maybe that will be worth trying in the future!

Yes, do it! Moving on to Extinguishment itself, are the three pieces conceived as ‘movements’ in one work, or are they each separate compositions?

BG: Our process in creating this album was not fixed, but iterative, with the goal being coherent and intuitive, rather than being guided by a compositional conceit. These pieces started with performance - recording, rendering ideal materials (“good sound”) - and later passing through stages of editing, arrangement and eventually titles and descriptions. This doesn’t feel like an arbitrary assignment, rather a structure that reveals itself naturally after the elements are in place. This process has come about gradually through years of playing together. We often start our sets with a rough idea or image, one of us usually says “I will start with this material” and we have sorted a signal which means “we should wrap this up,” but otherwise we let a performance develop as it will.

On this album, each track stems from discrete improvisations. While the pieces retain identities they use a common language which ties them together as an album. Each track began with a recording from a dedicated session which was layered and combined with live recordings from our tour last summer, so each session take was paired with one tour take. Additional raw material was added while we were editing.

AG: A note on the title: as we were wrapping up this process we came across a concept called socionics, which seemed to resonate with what we were doing. Socionics appears to describe the psychology of interpersonal relations. In particular, the relation of “extinguishment” described quite closely our experience of creating this album. Our understanding of this concept is that extinguishment occurs between two very similar individuals who share an idea, but approach it in different ways or come to different conclusions. This difference creates the collaboration in our practice.

That’s nice; I suspect socionics could generally provide a much richer set of tools for exploring authorship in experimental music than the received notion of the composer creating in splendid isolation. It’s interesting that – on the pieces on Extinguishment at least - you use improvised material as the starting point for the process of composition that you describe. In theory you could work in a similar way, but using pre-composed fragments, or found musical material (similar to the way you use field recordings). Is there a quality to improvised material that particularly attracts you?

BG: Our most salient sonic dialogue tends to arise from a subconscious, instinctive response while listening to each other and our environment. Practically speaking, the more we try to control our output, the less interesting it gets, although we often benefit from some simple yet flexible boundaries. Of course, this pure stream-of-consciousness material still requires editing, shaping and layering after the fact. Working with improvised material is similar to working with field recordings, in that it produces a large chunk of audio we can mine for novel and resonant events/timings that wouldn’t be available through a more traditional means of composition. As a duo, we come to ideas through practice and performance, not as much by creating in isolation. We don’t have a particular statement we are trying to make. We have a practice through which a space for expression is formed, and that is where we feel most articulate.

Finally what future projects do you both have in preparation? How are we likely to hear from each of you next?

AG: Most immediately, Billy will have a solo LP issued by Students Of Decay this summer. Also in the pipeline is a quartet we recorded with Richard Kamerman and Takahiro Kawaguchi in 2011, which will be published by Winds Measure sometime this year. And I just played some concerts in Europe, and the material from those performances will likely be expanded into a solo album over the next year. Also I have agreed to write a short composition for the Anagram Ensemble to be performed in October 2015. In addition to that we’ll play some more concerts here and there as things go.

Discount price £5