Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

Interview with Kerry Yong

The first time I saw you perform - many years ago, I think before you'd played with Apartment House - you were playing Cage. Not early Cage, but spiky middle-age Cage, with an electronic keyboard programmed to make all sorts of unlikely sounds. So tell us, when did you first encounter Cage's music, and has it affected your development as a performer?

I think you heard a project I started in the early 2010s, which I ended up calling Cover Me Cage. It followed an earlier project called Cover Me Casio, which were disparate post-war pieces 'covered' or re-imagined on a lo-fi 80s Casio keyboard and guitar effects pedals. The first cover was made as a way of keeping a performance: the concert organiser had discovered that the piano in the venue was no longer there as it was simply hired for a one-off event. She wondered if there was a way to keep the pieces by presenting them in some other form. They were part electronic anyway, so it wasn't too great a stretch of the imagination to push them into a completely electronic world. This led to exploring other possible works, and a natural progression was to explore other 'classics' of a sort (things by Messiaen, Stockhausen, Scelsi, Ligeti). I think I did stay faithful to their spirit - but the limitations, timbres and effects available on a Casio and pedals certainly posed another 'take' on the pieces. They were elements the pieces already had, but were exaggerated or taken in another direction, as all arrangements ultimately do.

The following Cage covers also had a pragmatism about them: besides a few pieces from the Sonatas and Interludes, many were short independent pieces for dance that rarely get performed live, or together, simply because each has a different piano preparation and the breaks that would be required to prepare them would be longer that the playing time! However, I saw little point in them simply making a portable version of the original sampled prepared piano sounds - they would always be inferior to the original sound and lose the delight in feeling and seeing a prepared piano in action. Rather, I substituted the prepared sounds for another sound: which could be electronic, synthetic, or recorded/sampled from another sonic world. There is then the problem of coherence and choice with having every sound available to you: so each piece has a family of sounds which distinguishes it, while also having some relationship to the original. So Cage's original prepared piano piece became a form of tablature for other sets of sounds. What transpired was that his rhythms and patterns were robust and ingenious, but also versatile and malleable - like a new sort of musical language or potential-music.

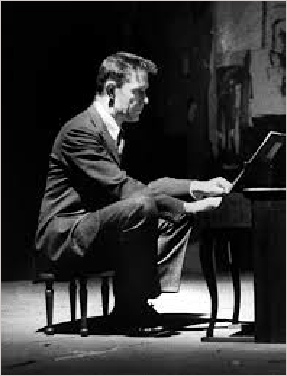

I first encountered John Cage's music as a teenager, growing up in Sydney, Australia. I had a great classroom music teacher at school, and we later became good friends and remain so. I think we watched a documentary about the dance music he wrote for Merce Cunningham, but I'm sure I also got to know works like First Construction In Metal then too. So I would say that this era was always the music I first associated with Cage. But this was in the context of discovering a whole range of diverse music - my piano teacher for some time, owned the only authentic harpsichord in Sydney, so I was exposed to a lot of early music, and via school was discovering lots of fascinating music from the twentieth-century. It was all exploration for me, so I think my development as a performer was geared very much to being able to realise compositional ideas. I think it's unavoidable, particularly through music college, to become aware of different classical piano schools of playing and I like the variety of playing styles that produced. But I realised it wasn't going to be particularly helpful for some of music I would explore later.

Before we say more about Cage, can we go back to your time in Australia? The musical education you had sounds great, but when you left musical college, did you try to make a living in Australia, or did you come to the UK very soon afterwards?

I vowed after I finished my Masters I would not do another research degree – I particularly found writing words really tough. I admire good writing and thinking, but felt I couldn’t do that very well! So I spent a little time in Sydney working as a musician, mostly teaching but some performing, particularly of new music, and I remember with great fondness playing in various Sydney Spring Festivals of New Music, run by Roger Woodward. But I think I always wanted to go overseas, as it was the done thing for the previous generation of musicians in Australia and still has purchase presently. It also didn’t take too long before I actually did crave a little more formal study, against my better judgement! So after gaining a scholarship from my alma mater, I took the plunge of moving to London and started a Doctorate at the Royal College of Music. The programme was quite new there and so there wasn’t a large cohort of researchers or performers in new music, but I realised that just being in London had great benefits and quickly got to know the new music scene here.

I do have my doctoral work (which looked at piano and electroacoustic music) to thank for the Cover Me Casio and Cover Me Cage projects although it wasn’t a straight line – more a serendipitous offshoot that worked out well for me. I developed some pieces for the series Kammerklang in east London and later for the Borealis Festival in Bergen and I think it was there where Anton saw them and subsequently invited me to play in Apartment House.

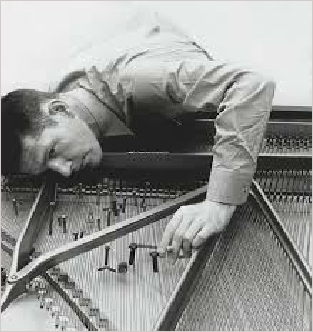

Earlier you referred to the ‘delight’ in experiencing a prepared piano performance. Does that still hold true for you today? You certainly seemed to enjoy setting up the piano for the recordings of ‘Amores’ and ‘Music for Marcel Duchamp’...

There is something quite ephemeral and special about the prepared piano – it’s mostly to do with how every instrument responds differently to these treatments but also that it’s not very exact, even if, in the case of Cage, is quite precise. His instructions seem quite prescriptive: although, unless you know actually piano model he was using and the objects he was talking about, you’re always making adjustments. The preparing is just like other notation – there is quite a bit of interpretation that needs to go on and a sort of listening out and imagining for what the crux of the matter is, as to what you are being asked for. But altering a fine piece of technological machinery always produces an interesting result. There is certainly a tactile and experimental pleasure in preparing a piano, as well as playing it. The sounds always seem magical, fresh and new and as a pianist, you feel a little bit like a fantasising and imposter percussionist. It’s also because it really does disrupt your tactile relationship with the instrument – it remains responsive to your touch, but altogether quite different. It’s not dissimilar to performing in a new space and getting acquainted and friendly with its acoustic and getting to know its distinctives and idiosyncrasies.

Don’t get me wrong, I think the modern Steinway is an extraordinary and exquisite instrument, incredibly responsive with a lovely range of colour – but it always comes out quite beautiful – even when you try to get it to bark, it tastes somewhat like melon! There’s also strange distance you feel from the instrument, and although this might sound unrelated, I can understand while a child learning the piano might get bored with what is involved in making sound on the piano – it’s relatively simple and fait accompli, even though I know this isn’t true. There is a lot more activity required by a performer to keep an air column or string vibrating and something they feel in starting, finishing, but most importantly, continuing the sound. I feel that is something that is potentially missing for piano playing, however, for me, playing a prepared piano, strangely puts me in that world of feeling its vibrations. But it could simply be that I’ve been involved in being inside the piano while preparing it, that psychologically has made me more invested in the sound I’m making – that somehow I’ve been involved in something akin to instrument making, fortunately with all the hard and most essential bits done for you.

I feel Cage’s early music has a wonderful balance between simply gorgeous / gorgeously simple pieces like ‘Dream’ and ‘In a Landscape’ on the one hand, and the often spikier pieces for prepared piano, which revel in a kind of trickster-like innovation. Do you see it in the same way?

Almost – I think types of music are sort of the same, but different expressions of that idea. They are both heavily invested in the beauty, or maybe the sensationalness of sound, whether that is what is considered traditionally beautiful, or other darker or weirder notions of beauty. To use the analogy of animals, not only the beauty of birds, but also insects, crustaceans and fish. And in the early music there is a lot of play with patterns – really simple games that can be improvised – so something you could think us as you’re playing, or patterns requiring you to first work out the possible permutation and trying them all. I think in Cage’s early music there’s also some in between – a willingness to play with patterns and then change when you feel you want to: a sort of responsiveness to the present, or other interruptions and other factors, e.g. dance. There always seem to be a good sense of play and freedom, grounded in a mixture of pragmatism and theory.

Lastly the ‘String Quartet in Four Parts’ (on which you obviously don’t play) and ‘Six Melodies’ (which I think you and Mira play really beautifully). These pieces were written one after the other, using the same compositional method, which Cage moved on form shortly afterwards as he began to explore various ways of using chance. I don’t regret Cage’s embrace of chance procedures, but I have some regrets that he never came back to the method he was using in these two pieces, as it seems wonderfully fertile. It’s a bit like the brief period in Schoenberg’s music when he abandoned tonality, but before he’d devised the 12-tone system. What do you think?

These transitional periods you mention - Schoenberg’s and Cage’s - are exciting and can produce extraordinary music. My suspicion is that for both Schoenberg and Cage, it was an acknowledgement that old methods weren’t adequate for what they were wanting to do, and they were forced to be guided by their instincts and intuition to extend them. It’s ironic though that intuition is guided by reflexes or senses that are probably developed by past long-term habits and ways of imagining that they are forced to trust and test. It strikes me as being quite a similar state as to improvisation, except in composing you have the option to deal with the inner voices of doubt and reflection on what you’ve just produced, and it probably requires a strong internal propulsion to get over the self-censoring that can happen. With Schoenberg, he ultimately couldn’t trust working like this for too long, and also had a theoretical agenda and anxieties. With Cage though, I’m more inclined to think that the discovery of the I-Ching/chance captivated him and he simply wanted to explore what it had to offer. But this might be my projection of what it was like - although it’s very interesting to ponder. Ultimately I think a composer produces better work when they are excited by the ideas and vision they have ahead of them. But I certainly agree that these works are from a special period in which Cage has managed to successfully negotiate trusting past intuitions and exploring new ways of composing.

at240 John Cage ‘Chamber Works 1943 - 1951’

Early works by John Cage played by Apartment House

1 ‘In a Landscape’ Kerry Yong, piano

2-7 ‘Six Melodies’ Mira Benjamin, violin Kerry Yong, piano

8-11 ‘Amores’ Simon Limbrick, percussion Kerry Yong, prepared piano

12 ‘Haikus’ Kerry Yong, piano

13-16 ‘String Quartet in Four Parts’ Gordon MacKay & Mira Benjamin, violins

Bridget Carey, viola Anton Lukoszevieze, cello

17 ‘Music for Marcel Duchamp’ Kerry Yong, prepared piano

18 ‘Dream’ Kerry Yong, piano Anton Lukoszevieze, cello

Kerry Yong