Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

at82 Frank Denyer - ‘Whispers’

1 - 17 Whispers (2010) Frank Denyer (voice & accessory instruments) Elisabeth Smalt (offstage violin) 20:38

18 Woman with Jinashi Shakuhachi (2008) Kiku Day (shakuhachi, voice, small percussion) 11:19

19 Riverine Delusions (2007) The Barton Workshop - Jos Zwaanenburg (bass flute), 8:42

John Anderson (bass clarinet), James Fulkerson (bass trombone), Marieke Keser (muted violin),

Anne Magda de Geus (muted cello), Jamie Swale (bass drum), Frank Denyer (percussion)

20 Two Voices with Axe (2008) Frank Denyer & Juliet Fraser (voices), Jos Zwaanenburg (flute), 14:01

Benjamin Gilmore (muted violin), Elisabeth Smalt (muted viola), Dario Calderone (muted double bass),

Pepe Garcia Rodriguez (percussion), Bob Gilmore (axe), Jamie Man (conductor)

21 A Woman Singing (2009) Juliet Fraser (voice) 11:54

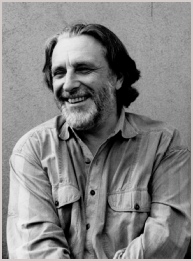

Sleevenotes by Bob Gilmore

‘Whispers’ was co-produced by Bob Gilmore, who sadly died before the disc was released. The CD is dedicated to Bob’s memory. Bob was a longstanding champion of Frank Denyer’s music, and wrote the notes both for this CD and for the previous Another Timbre release of Denyer’s Music for Shakuhachi which you can read here. In 2014 Bob also created an audio documentary about Denyer’s music - one of his excellent series of programmes entitled Tentative Affinities, which you can listen to on his website here.

Here are Bob’s sleevenotes for the ‘Whispers’ CD:

“The experience of listening to Frank Denyer’s music is extraordinary, quite distinct from other aspects of our contemporary musical lives. His music manifests an exquisite sensitivity to sound, often unusual or fragile sounds; his compositions are more concerned with what can be heard than with an interest in systems, or drama, or “ideas”. And while these sounds sometimes seem to embody a covert narrative of sorts, as though a story is hiding, waiting to be told, any such narratives are never made explicit. This leaves the listener free to concentrate on the highly original melodic lines, the harmonies and the unique tone colours of Denyer’s work, while speculating, if desired, about possible scenarios that may lie behind. This disc, the eighth devoted entirely to his music, collects three solo and two ensemble pieces, and forms a portrait of his recent work, from the years 2007-10.

Whispers, for solo voice with ancillary instruments and offstage muted violin, marks a radical (and, so far, a one-off) change in Denyer’s working methods. Whereas his pieces generally emerge from a long gestation period, this one arrived suddenly; he began by writing down a few phrases one morning, not thinking in terms of longer spans. About five of its movements were composed in this way, on the day he began work. It is the first piece of his to be a mosaic of short movements, some very short indeed. Denyer found that the gaps between the individual movements needed to be very exact, some of them quite long, so by trial and error he determined a series of lengths which are specified in the final score. Like the earlier Riverine Delusions, but in a very different way, this piece led him to think of time very differently than in his earlier music. The piece was not specifically intended for his own voice, but Denyer’s performance here offers a marvellous sense of immediacy, as though the pieces are coming into existence as we listen. The very quiet, fragmentary music of an offstage muted violin is heard unexpectedly in piece fourteen, as though briefly opening up the performance space to a world outside.

Woman with Jinashi Shakuhachi is the second in a set of pieces intended for solo female performer. In 2004 Denyer composed a solo work for the Dutch viola player Elisabeth Smalt entitled Woman, Viola and Crow, in which the performer also has to sing, shake a set of rattles worn on her back, make footsteps of a quite specific timbre, and imitate (vocally) the call of a crow. Five years later, responding to a request from shakuhachi player Kiku Day, he wrote the second of what would become a set of four works with a woman performer in mind. Part of the stimulus was that Day played the jinashi shakuhachi, the original shakuhachi associated with mendicant Buddhist priests, made without any lacquer on the inside, and which women were traditionally forbidden from playing. He especially loved the very soft notes on the instrument, similar in quality to the human voice, and so the player also sings and, in addition, makes percussive taps with a thimble on the body of the instrument. In the context of Denyer’s output, this marks the drawing of a line after the many compositions he wrote for the shakuhachi master Yoshikazu Iwamoto in the decades up to 1999 (four of them collected on Another Timbre at03): Woman with Jinashi Shakuhachi takes a new approach to an instrument that has featured extensively in Denyer’s work.

Riverine Delusions is the earliest of the pieces recorded here, and was the last piece Denyer composed for the Amsterdam-based ensemble The Barton Workshop (with which he had performed, as pianist, for more than fifteen years) before the ensemble’s demise. But the work is less an act of closure than of new beginnings. A more flexible attitude to time is one aspect of this; atypically for Denyer, the score includes a few passages of unsynchronised material. So too is the striving for a more linear continuity, for ever-longer spans of music. The piece began life as a trio for flute, clarinet and trombone, but Denyer found it unsatisfactory in that form, so he rewrote it, adding violin and cello (both muted) and percussion. The work, the composer says, contains “some of the subtlest things I’ve done”: one example is the quiet, unison microtonal melody on bass flute and bass clarinet, so accurately played here that it seems like only one instrument. Like a river, perhaps, the piece has no clear beginning and end, as though a passing fragment of a more continuous music.

The ensemble piece Two Voices with Axe calls for three different types of sound source: two voices (female and male), an ensemble of five instrumentalists, and an eighth performer who slices into wood with a large axe. While these three elements are sonically distinct, the piece finds all manner of connections and dialogues between them. Quite unlike the music that surrounds it, the axe is a loud and even a violent presence. No two sounds produced by the interaction of axe blade and wood will ever be the same, hence yielding a range of timbral unpredictability. The other percussion, in contrast, while occasionally echoing the axe with gentle knocking sounds, is wholly different in function and sonority. The vocal writing, by extending the female voice downwards and the male voice upwards, makes them at times indistinguishable, so that it is not always clear which singer is producing any given sound. But just as significant as its extraordinary timbral world is the melodic nature of Two Voices with Axe; the concern to make long melodic lines has been a recurrent feature of Denyer’s work for over four decades.

The closing work, A Woman Singing, is the fourth in Denyer’s series of works for female performer. Here the singer must strive for what he calls a “painfully intimate tone of voice”, almost as though she were singing to herself. Heard in this way, the work is a stream of consciousness in which the very gentle sounds - as though the performer were engaged in another task while softly singing - are occasionally interrupted by words, like fragments of an inner monologue. In concert, the piece would at times hover on the threshold of audibility. The special intimacy afforded by CD, where we as listeners can feel very close to the sounds, gives us privileged access to the very special tones of voice that characterise Denyer’s remarkable output.”

Bob Gilmore, August 2014

The audience would initially dismiss it as extraneous, as ‘not music’, and some would hope that the issue would be quickly dealt with, but I fondly imagined that eventually they would see that this too was music, indeed a refined and delicate music that perhaps deserved their attention. Later, when I actually got down to work, it quickly became clear that the musical effectiveness of each tiny piece was dependent on the precise sequence and the length of the silences between them. So these fragmentary miniatures coalesced as a single whole and consequently my initial idea of interspersing different fragments into another kind of musical event slowly faded.

In much of my music I have used offstage instruments, and/or voices, to suggest worlds beyond the confines of the concert hall. At rare moments these sounds quietly seep into the hall, revealing themselves to have a secret resonance with the music’s hidden core.

When I was a young ethnomusicologist in East Africa working with the Plains Pokot, I was interested to discover that the more potent the song the softer it was sung, and very significant texts, such as those of the cattle songs composed by each individual adult male, were sung in a whisper. The songs used by itinerant healers to curse disease were an even more extreme example. I remember recording a sequence of them sung by a female healer where the rapt audience of about a hundred could barely hear anything because it was so very soft.

There are many and various circumstances when we all find it natural to sing or intone softly in an under-voice, almost to ourselves. Anyone familiar with patients in deep trauma will be familiar with this, as will anyone watching children grow up. The emotional connotations when we revert to this secret under-voice are extremely varied and diverse. These are mysterious areas which interest me as a composer, and as someone who seeks a better understanding of the very diverse roles music has in human life.

I love the way that the next piece – Woman with Jinashi Shakuhachi – flows on seamlessly from Whispers as if it’s a continuation of the same piece, but then moves into a slightly different area. As Bob Gilmore’s notes say, you’ve composed a lot of music for the shakuhachi. What do you particularly like about the instrument, and how does this new piece ‘take a new approach to the instrument’, as Bob wrote?

For me the shakuhachi opened the door to a world beyond that defined by the aesthetic obsessions and conceptions of my education. In honkyoku, its traditional music, the self-sufficiency of the individual line derives from an approach to linear development that is born from quite different preoccupations. These are not defined intellectually but are built into the specific playing techniques and the player’s whole relationship with the instrument and its aesthetics.

Like many others in the sixties, my first introduction to the shakuhachi was through the famous Nonesuch recording by Goro Yamaguchi. In fact it was this recording that was partly responsible for me studying ethnomusicology at Wesleyan University, Connecticut USA. There I first met the great shakuhachi master Yoshikazu Iwamoto (he was actually my neighbour). He had come to the music department for a year as Artist in Residence and I was intensely studying the koto as part of my research and so we got to know each other. On his final day when he left to return to Japan, somewhat out of the blue, he asked me to write some music for him. He believed the shakuhachi, despite its impressive history and repertoire, was just at the beginning of its development, as it was emerging from its previous confines of Japan and entering a wider world. Slowly, over the next two decades, particularly after he came to work at Dartington in 1982, we were able to expand the range of the instrument and develop many new techniques through the new works I composed for him. This culminated in 1997 with Unnamed, a 47 minute solo piece using a number of different tuning systems. Soon after this Iwamoto gradually stopped playing in public and I thought that would be the end of my shakuhachi composing life as there were no obvious signs of new players coming along who were either willing or able to continue the ambitious path he had begun.

Then one day Kiku Day, a young Danish/Japanese player, contacted me to say she was studying several of my pieces, in particular The Tender Sadness of Tyrants as they Dance for shakuhachi and bass flute. I was astonished that she should approach such a formidable task. Much later Kiku asked if I might compose a new piece specifically for her as she was particularly interested in developing a new repertoire for the jinashi shakuhachi, a neglected older form of the instrument. Its basic sound is rougher and more breathy than the standard instrument but I was attracted by its very soft tones, particularly in the lower octave. I discovered that when isolated, they have a quite striking similarity to the human voice.

I suppose that what Bob saw as a new approach was my decision to prioritise just this one part of the instrument and to emphasise the intimate relationship with the player’s singing voice. In the past women were unable to enter the shakuhachi world and through the title, Woman with Jinashi Shakuhachi, I wanted to underline Kiku’s quiet contemporary challenge to this tradition.

Many of your works have distinctive and evocative titles, for instance Towards The Darkness, I Await the Sea’s Red Hibiscus, Contained in a Strange Garden, Beneath the Fired City etc. So where does the title of the next piece – Riverine Delusions - come from, and what does it refer to?

This piece started with my wanting to make something for my long time friends in the Barton Workshop, Jim Fulkerson, Jos Zwaanenburg and John Anderson. They made a trio of bass trombone, bass flute and bass clarinet, plus there was to be a part for myself playing light, mainly rubbed, percussion. It was written for a tour of the USA. During those days, apart from composition, I was plagued by a recurring image of a great river at night, a huge body of water silently making its way through a sleeping city and on through the countryside. It appeared as a great linear form whose temporal continuity is forever in flux, a vaguely defined presence without any perceptible beginning or ending. These thoughts certainly suggested the form of the piece but beyond that I wouldn’t like to go. It is in no way a descriptive piece but more a continuation of my peculiar musical preoccupations. Then why mention rivers? Why indeed! Where do such images come from, why are they are so persistent and what actual influence do they exert over on either life or music? They are mere fragments of imagination. And because the music was written long before I found this particular title, I cannot now be sure how much my memory has been influenced retrospectively, as I tried to better understand the title.

Anyway, eventually the piece took shape and in the course of time we took it on tour. But nevertheless something about this original version remained unresolved and unsatisfactory. It nagged at me, and so, later on, I musically re-thought the whole thing and undertook a root and branch re-composition, adding the violin and cello parts (both with practice mutes) and the second percussionist (bass drum).

Two Voices with Axe is pretty much what it says on the can – though there are also five instruments playing softly. It’s an extraordinary piece in which the fragile instrumental and vocal sounds are interrupted at irregular intervals by the deafening sound of an axe crashing into a block of wood. In his excellent audio documentary about your music in his ‘Tentative Affinities’ series, Bob Gilmore identified a general tendency across several of your pieces in the past 20 years whereby “extreme stillness is often shattered by very loud bangs….as though our attempts to make a quiet, delicate and subtle music are repeatedly being destroyed by a brutal force coming from we know not where.” So where does this aesthetic of catastrophe come from, and what does it signify?

Perhaps I can approach this from a purely musical point of view. I first worked on the very quiet sections but at a certain juncture, reviewing what I had done, I felt the quietude was becoming just too self-contained and in danger of seeming a self-sufficient ‘protected’ enclave, perhaps an insipid utopia. This was not what I intended at all. To alleviate this problem it required some ‘other’ entity from outside, something quite extraneous, something rough and physical that would appear as a threat, a destructive force. Thus the axe.

It has been pointed out that tapping, knocking, hammering and suchlike have permeated my music more or less from the beginning. However, I only became conscious of this in my mid 40’s after the premiere of Quartet in 1990 when someone came up to me and said ‘what are all these knocking sounds about?’ It took me by surprise and I heard myself reply; ‘what knocking sounds?’ Since then I notice that they quite regularly recur and in various guises, sometimes as soft punctuation, as in Woman with Jinashi Shakuhachi, or Whispers, sometimes more forcefully as here. Exactly what they might signify is difficult to say, but they insist on being there, and each time they solve a different kind of musical problem.

The album ends with A Woman Singing, which again uses the voice in an intimate, almost physical closeness, about as far removed from operatic grandiosity as you can get. I'm interested in the physicality of performance in your work, not just with voices but with instruments too. It seems that more than usually, your music isn't intended to exist on an abstract or immaterial plane, but is very much grounded in human bodies engaging physically with objects or instruments, and is run through with lived, biological rhythms. Does this make sense to you? And is it partly why you have never gone in much for using tapes, field recordings or electronic instruments?

You have put your finger on something that is quite central to my work. Writing for the solo human voice is for me the equivalent of a painter needing to engage with the nude human body. The unaccompanied solo voice reveals us in all our nakedness and nothing can be hidden except through rhetoric and drama. So I usually try to cut the voice back in the attempt to also minimise these final veils.

The voice can be extended through musical instruments which offer (amongst other things) a more ideal singing voice than the human vocal chords can encompass. Instruments are never merely inanimate tools to produce sounds. They become a mediation between inner and outer worlds, deriving their potency by their internal and external contact with the player’s body via breath, lips or limbs. However, this interface can only become sufficiently sensitised by the specific physical skills nurtured over years of daily practice. Therefore practising, rehearsing and study have inherent meaning as vital parts of a single nexus that makes the musical life, not of value merely as preparation for a public show. From this whole nexus comes the special bond between player and instrument. Every sound becomes intimately bound to a corresponding bodily movement, however discrete, so that sound and body movement become synonyms for each other.

The following is one illustration of the intimate identification between instrument and player. I once went to see the eminent Indian sitarist Imrat Khan. When I arrived at his house he told me that although he had never previously drunk alcohol, he had nevertheless decided that morning that he wanted to know why people were so obsessed with it. So, in the spirit of enquiry he had consumed more than half a bottle of wine. ‘And what has been the effect?’ I asked tentatively. ‘Oh! it hasn’t affected me in the least’ he replied jauntily, ‘but.....it has had a rather strange effect on my sitar.’

As a musician I am still mesmerised by that initial contact with the visceral physicality of an instrument, its materiality. Each day it is recreated anew. That magical moment when bow first meets string, or the first sound producing breath appears, or finger finds the familiar ivory, wood or metal, and in each case sound is conjured from thin air. And after this moment - the line, always the line.

As far as performance is concerned, live acoustic performance is my ideal and I think my music tends to work best in performances before smaller, more intimate audiences.

Interview with Frank Denyer

All of your music has been personal and idiosyncratic, but Whispers seems to represent a further turn in this direction. Listening to the title piece in particular feels almost like an invasion of privacy, as though we're hearing an old man humming and gently singing to himself in the corner of his front room. It doesn't feel like a musical performance at all. Can you tell us how the piece emerged, and whether you see it in these terms?

Whispers started when I was asked to write a piece that would fit into a traditional classical concert programme. This was an unusual request considering the nature of my work, but I wondered if I could respond in some way. I stared to imagine a classical concert but with another kind of music arising from time to time, not from the stage, but from somewhere else in the auditorium, the sound of someone (not necessarily old) singing very softly to themselves.

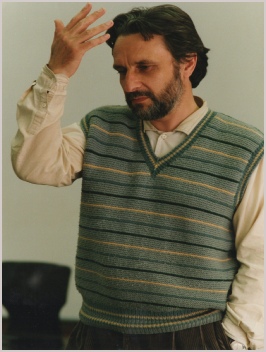

Frank Denyer

Reviews

“If only for having the advantage of hindsight, it may be easier to rediscover the past than to discover the present. I got sent some new CDs from Another Timbre, the label that’s been putting out essential recordings of music by Laurence Crane, James Saunders, Bryn Harrison, Catherine Lamb, etc etc. One of these discs is a collection of pieces by Frank Denyer.

I’d been aware of Denyer mostly as a musician, and from his work with The Barton Workshop. It was only on hearing a broadcast of his piece The Colours of Jellyfish for soprano, children’s chorus and orchestra that I realised he was a composer with a unique voice. The pieces on this new disc, Whispers, are a few years older than that orchestral piece, and recorded mostly in 2009: a neat example of rediscovering the present.

This album can be shocking in places. Even more spare and seemingly artless than I expected, the music takes familiar techniques but approaches them from a new angle, creating a paradoxical mood that quietly works on the listener. There’s a tense feeling of expectation, or apprehension; not from the music itself, but from my wariness of what it might all turn out to mean.

The opening piece, Whispers, is about precisely that: Denyer himself whispering, humming, muttering, a halting procession of small vocal sounds. Like a man half-singing, absent-mindedly to himself. Listening in seems almost intrusive, but there are other things going on: small tappings and rustlings from various noisemakers, and at times a viola plays almost inaudibly in the distance. (The entire album is recorded very quietly, suggesting that without careful listening much of it may be lost.) The sounds vacillate between unconscious and self-conscious, the act of producing them at the same level of intensity and restraint over 20 minutes denies any accusation of self-indulgence or even self-expression. The meaning remains as unknowable, or knowable, as any unconscious sound.

The entire album flows seamlessly from one piece to the next. Woman with Jinashi Shakuhachi is, like Whispers, precisely what the title describes. The mouth sounds change to the musician Kiku Day’s voice, alternating with raw shakuhachi sounds until the two lose distinction, and again the tapping sounds. It’s tempting to think of the music as some sort of ritual, but again the ordering of sounds is too organic, too intimate. Again the sounds seem almost unconscious, as though they were the by-product of some other activity that remains unknown.

As an interlude, The Barton Workshop’s performance of Riverine Delusions may be the most conventional piece here – it’s evocative, but the image it paints is almost transparent, with faint gestures suggesting big movements, the indelible remnants of an image faded almost to invisibility. The keening flute stands out in relief, a preparation for the next work. Again, the title Two Voices with Axe explains everything but reveals nothing. A male and female voice blend in a tissue of sounds with muted instruments. The jarring intrusion of the axe comes almost as a release, breaking the tension of expectation that something loud might finally happen. Despite the most private and personal circumstances of the music-making here, the music that emerges from it is like a wild force of nature – it always seems peaceful and benign on the surface, but all along I’ve been conscious that it could turn on me without warning.

The axe-blows sound rich and varied, with no suggestion that they were contrived for aesthetic effect. The late Bob Gilmore, who produced the album, is the axeman.

In the final piece, A Woman Singing, Juliet Fraser’s voice mirrors the opening of the album. Again barely audible when played under normal conditions, the voice is suspended in a stream of unconsciousness, the emotional range suppressed to a nearly internalised expression. By being so withdrawn, the singer’s exposure feels all the more stark, through the lack of mediation, the temptation to listen in closer, like an eavesdropper.

These works are not improvised but fully, meticulously composed. There is a fine, complex understanding of the subtleties of music at work here, of the material of sound, the acting of performing and the relationship of musician to listener. At first the sound world seems close to the very refined sensibility of Martin Iddon’s excellent pneuma, which Another Timbre released last year. Denyer’s approach and musical concerns are different, of course, and so is his music: this is made evident, however, not through any ideological or programmatic pronouncement, but through the very stuff of the music itself, that entices and gnaws at the listener. The reactions this music may provoke are complex and variable, and I would not like to try to define them now.”

Ben Harper, Boring Like a Drill

“London-born musician and composer Frank Denyer enjoys a reputation that is belied by his relatively sparse discography, Whispers being only his fifth album since the millennium and his first since Silenced Voices (Mode, 2008). Whispers and Silenced Voices make fitting titles for Denyer compositions and albums, as he has displayed an increasing affection for quieter compositions. On the current album, the composition "Whispers" dominates, consisting of seventeen short vocal pieces, with a total duration of less than twenty-one minutes; performed quietly by Denyer with his sustained wordless tones only being accompanied by occasional spoken words, whistling or tapping from himself, or muted violin courtesy from Elisabeth Smalt, at times the overall effect can feel like eavesdropping on a séance. Denyer sounds extremely vulnerable, and the most immediate reaction to this may be one of embarrassment at intruding on a very personal, private experience. Nonetheless, with repeated listenings, over time the piece's fragile, delicate atmosphere becomes compellingly listenable and very memorable.

The remainder of the album, recorded between 2009 and 2013, revisits other aspects of Denyer's music. His only previous album on Another Timbre was 2007's Music for Shakuhachi , featuring Yoshikazu Iwamoto playing shakuhachi on nine tracks recorded between 1984 and 1999. His work with Yoshikazu was important in Denyer's musical development and, on the current album, "Woman with Jinashi Shakuhachi" (dating from 2011) is a welcome reminder of that music while building upon it. On the piece, in a fresh approach to the instrument, Kiku Day combines it with her voice and percussion to create a coherent soundscape that is both charming and engaging. The following track, "Riverine Delusions" features The Barton Workshop, the (usually) seven-piece group founded by Denyer in 1990 to perform his music and that of other composers. Although, in recent years, they have released more albums of other composers (Wolff, Lucier, Cage, Feldman...) than of Denyer, he remains an occasional member, playing piano or, as here, percussion. The instrumental line-up of bass flute, bass clarinet, bass trombone, bass drum, muted violin, muted cello and percussion gives a good idea of the soundscape, but it cannot hint at how integrated and comfortable the players sound with one another, the result of much time playing together. Impressive.

The dramatically titled "Two Voices with Axe" combines the voices of Denyer and Juliet Fraser with an axe wielded by Denyer's long-time producer and writer of sleeve notes Bob Gilmore, all accompanied by a small ensemble conducted by Jamie Man. The delicacy of the voices and accompaniment is effectively contrasted with the intermittent noisy interjections from the axe, creating a dynamic tension between the two. (Sadly, Gilmore passed away in 2015, so the CD is dedicated to him.) The album closes with a track that almost takes us full circle; on "A Woman Singing", Juliet Fraser sings alone, unaccompanied, at times sounding almost as exposed as Denyer did on "Whispers". Established Denyer aficionados will find Whispers well up to Denyer's usual high standards, while the uninitiated or curious can start here with confidence.”

John Eyles, Squid’s Ear

Special offer £5