Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

home CD shop 1:recent discs CD shop 2:older disc sale online projects index of musicians texts orders submissions contact links

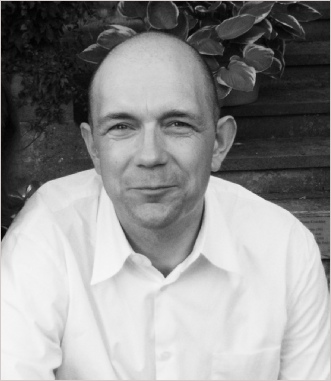

Interview with Laurence Crane

I don’t know how much time you spend reading your Wikipedia entry, but it quotes a programme note where you describe your music: "I use simple and basic musical objects; common chords and intervals, arpeggios, drones, cadences, fragments of scales and melodies. The materials may seem familiar - perhaps even rather ordinary - but my aim is to find a fresh beauty in these objects by placing them in new structural and formal contexts..." Could you expand on that a bit?

My materials have their basis in tonality but for various reasons – historical, aesthetic and personal – I am not interested in deploying these materials using traditional rhetoric. Therefore I end up treating them like found objects and arranging and positioning them in very different contexts from what their possible historical resonance might suggest. I use repetition a lot, so you get something like a standard cadential formula or a sequence of ordinary triads, and by subjecting them to some sort of process of repetition, or interweaving them with something else, you get to look at this object in something of a new light. I invent these objects – they’re not quotes – and they seem initially to be quite familiar, ordinary or anonymous. I want the objects that I use to sound old AND new at the same time.

So are you trying to make the ordinary strange in the way that the Russian formalists were?

I’m not consciously trying to make them strange but realise that things might come out sounding a bit strange. I think there’s a danger in saying things like ‘I am going to make this strange’ or ‘I am going to be ironic’; if you flag it up too much then I think it’s a bit dodgy, a bit contrived.

[laughs]

In the recent interview in The Wire, Brian Morton asked me about this, about how it came about that I developed this particular aspect of my work. I can’t say that one day I woke up and said ‘This is what I am going to do’. Like most composers I just evolved my own techniques and ways of doing things. But then once you’ve done this, you have to be committed and make a big leap of faith. I’ve never thought ‘I must do this’ for any particular reason; I just move from piece to piece and things evolve, things happen that I want to explore.

There’s no personal manifesto then?

Definitely not. I’d rather leave things more ambiguous than that. If you write a manifesto you have to stick to it and I like to be able to deviate a bit if there's something interesting to explore.

[Laughs]

One thing that strikes me about your music is that it has a distinctive sound, which isn’t really like anyone else’s music. The earliest pieces I’ve heard are from the early 80’s, and right through to now, over 30 years on, it’s all recognisably Laurence Crane. There are slight stylistic shifts across that period, but you seem to have found a distinct voice very young. Do you think that’s true?

I suppose so, yes. The earliest pieces I still acknowledge are from 1983-1985, when I was between 22 and 24 years old. I wrote this piece called ‘Three Melodies’ for flute and piano, which is the first piece in my recognisable style. But in a way it did involve a specific response to another composer - Howard Skempton. I encountered Howard’s music for the first time in 1981 when a fellow student at Nottingham University played six pieces from Howard’s early volume of piano music, which very strangely had been published by Faber Music in 1971. And that was a pivotal moment for me; the idea that you could compose music like this. It was the realisation that you could write music that was completely stripped of its fussiness, and also that you could use material in the way that he did. These pieces were broadly speaking tonal - they used objects that were tonal - but were free from their original implications. It took me quite a while to assimilate that into my own style, and it wasn’t until late 1983 when I started writing my Three Melodies. If I played that piece now you might recognise a certain sparseness, I think it's recognisably me but harmonically and gesturally it’s different from the music I write now, 30 years on.

I was trying to think of other composers whose music was like yours in some way, and I was struggling. But I can see that there is a connection with some of Howard Skempton’s music, his piano music….

Particularly the early piano music, it's wonderful. I think perhaps his later work comes from a different world from mine, I don't feel so much connection with the more recent work, I think my music is more objective in a way.

What do you mean by ‘objective’? That it’s less emotionally charged?

Possibly. Not sure.

For me with music that’s tonally or harmonically based, it’s like there’s a line that it’s very easy to cross where the emotional aspect of the music becomes sentimental or over-romantic. Somehow your music always manages to stay on the right side of that line, so I find it really beautiful, partly because it retains a quality of starkness. But for me most composers who tread that tonal path end up tipping over into a kind of cloying sweetness that I find repellent. Do you have that sense of there being a borderline or a tipping point as well?

Yes, I know what you mean and I am aware of it. And it sometimes is a very fine line. I said that my music was ‘objective’, but I know some people who like it and find its 'beauty' very moving, so is that ‘objective’? I don’t know. Other people might view it differently. But there is definitely a lot of other music that I find ridiculously overwrought and self-indulgent and I think I want to create some sort of antidote to that.

The Håkon Stene CD (‘Lush Laments for Lazy Mammal’) that came out recently, and which contains several of my pieces, got an interesting review in The Times. It was reviewed in the category ‘world’, which amused me (the review in the ‘classical’ section next to it was something by Harrison Birtwistle). It’s a tiny review but the reviewer loved the CD and said my music “makes almost all other music look fussy and overwrought”.

[laughs]

But going back to the ‘objective’ thing, it’s complicated. When I think sometimes of what very objective music might be I think of a composer like Tom Johnson and I don’t really like his music because it’s too much about the process. In my work I like to move away from the process sometimes and I’m more interested in the sound of the music rather than in the process for its own sake.

Thinking about what ‘objective’ might mean in relation to your music, I remember when we were editing your piece ‘Estonia’ for the album, you wanted to reduce the volume of the final bars because the way we had combined different takes at the end made it sound like it was building to a crescendo and you didn’t like that.

I suppose a good performance of a piece of mine would have a balance between objectivity and subjectivity in the sense that if you play the piece in a very understated, matter-of-fact way, any beauty in it will rise to the surface but not in an overdone way. The original ending of ‘Estonia’ as we had edited it, because of that particular combination of takes, veered towards some kind of climactic point, which felt wrong.

So it’s like the notes in themselves always already contain a strong emotional force and you don’t want the playing of them to add any icing on top of that?

Yes, but sometimes it’s difficult to communicate that to some performers; training and what has been already learnt get in the way. I like to leave my scores clean, stripped of unnecessary detail. It’s an aesthetic thing because I feel the ‘cleanliness’ of the score matches my aesthetic aims. But performers who aren’t familiar with my music, or music of similar aesthetic intention, might take that as a licence to ‘interpret’, to inject some kind of expressive intent into the music, which it doesn’t need.

Yes, I think your scores do look like the music sounds. They’re meticulously prepared, bare, with a minimum of text…

But with some of my recent pieces, like my Piano Quintet, I have used more verbal descriptions in the score because the music is doing something slightly different. It has much more of a directional thrust as a piece, as do other recent works, ‘Classic Stride and Glide’, 'West Sussex Folk Material', 'Chamber Symphony' and 'Octet'. And in 'Len Valley Us', a new piano piece that I wrote for Tim Parkinson, every movement has a written description to give the player an idea of the approach to take. Structurally those new pieces are closest to ‘Piano Piece No. 23’ on the disc, which has discrete sections - but in 'Piano Piece No.23' the character doesn’t change too much across the piece as a whole, in the Piano Quintet it does change considerably and this is reflected in the character markings in the score.

Apart from Howard Skempton’s early music, are there other composers with whom you feel a connection?

There are quite a few, I’m not sure I can be exhaustive here so I’ll restrict my answer a bit; the obvious ones from the last 100 years are Feldman and Satie. And I am always interested in the music that composer colleagues, friends and contemporaries are writing, for example James Saunders. I think his music is wonderful and I think I can say that in ‘Four Miniatures’ I brought in an element of timbre-based composition, and that was definitely a sort of response to his music. Also the recent piano piece for Tim Parkinson that I just mentioned, I wrote it for several reasons; for Tim because it was a big birthday for him last year and also I was using it as a way of writing myself out of a kind of block, trying to see a way through to something else. But it was also in part a homage to Tim’s music, which I also love, though the piece definitely sounds like me – just as ‘Four Miniatures’ sounds like me and not like James - but sometimes I do latch on to something that someone’s done, and think “well it’d be interesting if I tried something like that”. It's a point of departure only; if you have enough of a strong personal voice then that will come through. Other contemporaries; I don't want to start listing them because of a possibility of missing someone out! I just mention those two – James Saunders and Tim Parkinson – because there are specific examples of me responding to their work in my own.

Why is the disc 1992-– 2009? Is that a distinct phase in your musical development? Or is it not that neat?

No, it’s certainly not that neat. It was simply because when we made the list of possible pieces that we could record they were all contained between these two dates! There are also 3 pieces from 1989 that we recorded; they are not going to be on the CD but will be available for download from the website.

.

Defining different phases in compositional work is difficult as there is a lot of overlap and, for me, changes happen gradually rather than suddenly. One thing that I would say about 1992 is that it was a year when I wrote a lot of pieces, by my rather unprolific standards, and I also stopped writing so many pieces for solo piano around that time. The CD of my piano music on Métier (‘20th Century Music’) is notionally pieces from 1985 to 1999, but in fact most of it is from 1985 – 1991. That’s partly because in those early years, in order to get my music played at all I had to play it myself, even though I’m not a proper pianist. So in my list of works before 1992 they’re almost all pieces for piano or piano plus one other instrument.

That illustrates something that must be true for a lot of composers: that their output is largely determined by what the playing opportunities are – and when they’re starting off that is bound to be limited. I was going to ask whether the title ‘Chamber Works 1992-2009’ indicated a particular commitment to chamber music as opposed to larger ensemble or orchestral works? Or is it simply a pragmatic thing which reflects the fact that initially the only people who would commission you were small groups, and it’s only as you have become better known that opportunities for larger pieces have emerged?

The latter, definitely. I am interested in writing for larger groups, and I have done a bit of that now in the past ten years. But on the other hand I do love chamber music and writing for small groups.

Going back three decades, at that time as a young composer in your 20’s or early 30’s one thing that you could do was to try to get your pieces taken on by SPNM (the Society for the Promotion of New Music) or by particular new music ensembles. But I always got rejections from SPNM and very few people were interested. One response to this might be to sit in your room and compose pieces and then moan about people not playing them, another would be to compose pieces and then put concerts on somewhere yourself. I decided on the latter response and I was very lucky because at that time we had the BMIC (British Music Information Centre) venue which was very easy and cheap to hire for concerts. And also there was the example of the English experimentalists – John White, Dave Smith, Michael Parsons, Howard Skempton. They all just got on and wrote pieces and put on concerts where they played the pieces themselves. I think that was why I started playing my own pieces in concerts. It was only later, in the early 1990s, when I met some of the musicians who play on this CD – Andrew Sparling and Nancy Ruffer – that I started writing pieces for a wider range of instruments. Then I met Anton Lukoszevieze in 1995 and he then started propagating performances of my music. Other groups and musicians took an interest after that and it stopped being so necessary for me to be involved as a performer.

So what did Anton see in your work that led him to start promoting you as a composer while bodies like SPNM were rejecting you?

I don’t know, you’d have to ask him

Perhaps I should.

Yes, you should. But it’s not just me; there are several other composers that Anton has taken up, performed and passionately promoted. I think he just has an instinct about the music and he decides that it’s for him. He’s very bold like that and doesn’t care about what people might think about him; he’ll just get on and play it if he likes it, there's no music scene politics involved at all.

A close mutual friend of ours, the Canadian composer Michael Oesterle, told me about a story from the 1990’s when Anton was in Canada and they had a long car journey somewhere together. Michael was driving and Anton kept loading cassettes into the car stereo and saying ‘listen to this...listen to this...you've got to listen to this’. That’s what Anton would do.

Coming from a different corner of contemporary music, for a long time I was aware of your music, and I liked it when I heard it, but I held it at arm’s length because it didn’t sound like the vast majority of the music about which I was passionate. I almost felt guilty that I liked it because its beauty was so in-your-face. It took quite a while for me to overcome that, which is stupid prejudice in retrospect, but I’m intrigued to see what will happen when it is heard by other people who are not into melody or harmony almost on principle.

Yes, I’m interested in that as well, and I am interested in all these divisions and niches within contemporary music. The Håkon Stene CD that I mentioned earlier has been reviewed as ’World Music’, and also on jazz sites and in rock and pop magazines and sometimes even as as modern classical! One person called it ‘new age’, which I found very offensive...

You don’t mind it being called jazz…

Well of course I do, but I can’t escape the fact that some of my chords might have been used in jazz.

In the text Michael Pisaro wrote about your music he mentioned Duchamp, which surprised me, but I can see what he means. Is there a connection there?

Not consciously, but I suppose there is a longstanding connection between the sort of music that I’m involved in and the visual arts – Cage and Duchamp had an artistic relationship, and Feldman was obsessed with painting and the methods of painting. My interest in visual art isn’t as explicit as that or as in, say, Bryn Harrison’s music, where it’s much more on the surface. But it’s possible to look at some of my music and recognise a process of walking around the same object and viewing it from different angles. Painting and music are obviously very different in how you experience them but then a lot of my pieces are very static so it is like you are walking round an object in space, taking in different views of it.

But I think what Michael was talking about with Duchamp is the idea of taking found objects and putting them in a new context. Then again I have to say that although I’m really interested in the way people experience my music, I don’t set out with a conscious aim or theory about it. Perhaps my methods do have something in common with the visual arts or film, but it’s something that has just happened through my experiences, rather than being something that I’ve deliberately set up.

Another metaphor that I’ve used before for thinking about my work is that of walking through a landscape, where the landscape remains essentially the same, but little details in it change, or come into and out of focus as you walk through it. So your experience when you’ve got to the endpoint will have changed, but the landscape itself has not changed much.

Another landscape metaphor struck me this morning when I was up at Kenwood House in Hampstead. I went to the viewing point that overlooks the grounds, and it looks fantastic and fantastically natural, but it’s actually an artificial landscape. Humphrey Repton, who was a leading landscape designer of the time, replanted the whole area, diverted the local watercourses and so on to create this amazing vista which looks totally natural, but is totally crafted. Perhaps that’s like your music as well. Michael wrote that he doesn’t know anyone who knows your work who thinks that it’s as straightforward as it sounds. I know that you compose quite slowly, so presumably Michael’s right, and it isn’t straightforward?

No it’s not. My critics would have it that it’s easy to do and that anyone can do it, but actually they’re wrong.

[laughs]

Is that kind of attitude something that you’ve had to fight from early on? I’ve no idea specifically why the SPNM were rejecting your pieces, but I can imagine that it was because they don’t sound modernist, they don’t tick the right boxes in terms of what people expect from contemporary music.

Yes, I know that there are some people who think that way.

So was it difficult in those early days to stick to your vision when you weren’t receiving any positive support?

Yes, but one thing about me is that I’m very stubborn and a bit dogged, sometimes too much for my own good. It helped in this respect, I think. And there’s also some sort of puritanical thing in me that thinks that struggle is a good thing.

30 to 35 years ago the situation was very different in the sense that there was more of a stylistic orthodoxy. Now when I see young composers writing music that isn’t specifically 'modernistic', there seem to be many more performance possibilities for them than there were for me at that time. It’s good that we have a much more pluralistic culture now. Perhaps there is still a prevalent orthodoxy to some extent in notated contemporary music, but music like mine is not just rejected out of hand now, as it was in the 1970s and 1980s in certain places where the power was wielded.

Then again, outside the classical world that period of the 60s and 70s is very resonant for me musically because my other great influence was rock and pop music. Like many composers I grew up listening to rock and classical music alongside each other, and I think that rock and pop music from that period has affected some aspects of my work; the use of the electric organ in the instrumentation of several works for example. I think that unless you’re completely shut off from the world, any composer born after the second world war is going to be interested in some other music apart from classical music, it’s all going to filter through. But that doesn’t mean that I approve of any sort of crossover music!

[laughs]

There’s a vocal piece of yours called ‘Tour de France Statistics’. I know that you’re a massive sports fan, and several of the titles of pieces on the disc refer to sportspeople, so you’re clearly not just being ironic when you write a piece whose lyrics consist of statistics from the Tour de France. But one thing that you’re obviously choosing not to do is use a poem by Mallarmé, or Joyce or Beckett in the way that, say, Boulez and Berio did. So what is going on? Is it not wanting to take yourself too seriously? Is it wanting to use humour? Is it irreverence? Is it wanting to say that music doesn’t have to be ‘deep’? I feel that this touches on a quality that runs through your work as a whole, not just the vocal pieces or the ones with bizarre titles; I think there’s an underlying attitude across all your music which I find very engaging, but I don’t fully understand what’s going on.

Yes, I should say that I wasn't being ironic at all when I set a list of statistics from the history of the Tour de France! If I were to come along and say ‘I’ve written this piece and in it I’m examining Adorno’s theory of….err…whatever’ (which reveals that I've never read Adorno because I can’t come up with anything); it would be dishonest of me to do that. In the piece you mention, ‘Tour de France Statistics 1903-2003’, it was simply a situation where you’re asked to write a piece and you respond to the brief as best you can, and in the most genuine way that you can. In that particular case, the two performers – Alison Smart and Katharine Durran, soprano and piano – commissioned twenty English composers to write songs in French. So some of the composers did set Mallarmé, but I decided that I didn’t want to set a poem because I don’t really read poetry. So for me it would be completely phoney to dive into a book of poems. And I thought, well, what are other ways of setting texts that are appropriate to my musical outlook? In this case the centenary of the Tour de France had just happened, so I thought why don’t I construct my own texts out of these statistical facts? I don’t speak French, but my dad does, so I wrote out the statistics in English and he translated them into French. So in the end it’s nothing more than trying to respond to things in the best and most honest way that you can.

Perhaps you not wanting to be showy or false in a pretentious way connects with the stripped down objectivity that we were talking about earlier?

Possibly. You could make a connection there. But maybe I’m just not geared up to read Adorno – perhaps I should try and do it some time. My extra-musical starting points are much more likely to be from the visual arts or film or things from everyday life rather than literature or any sort of theoretical approach.

Do people sometimes assume that your work is ‘conceptual’?

Yes, sometimes they do…

And are they wrong?

Yes, they’re wrong.

[Laughs]

Go back to page about Laurence Crane ‘Chamber Works’ CD

Anton Lukoszevieze on Laurence Crane

“I can’t remember exactly how I came across Larry’s music. It must have been something to do with the 90’s, experimental music and London. I heard about it before I’d listened to any, and I think I’d met Larry before hearing his music as well. Perhaps I’d heard someone talk about his seminal work ‘Weirdi’, or Andrew Sparling as a fellow musician introduced me to his music.

I felt that Larry’s music was always itself; it struck me as being the most perfect and effortless kind of art. The kind produced by people like Agnes Martin, Samuel Beckett and Harry Callahan. When I did hear it and looked at his scores, I knew it was some of the most essential music being written, which is why I performed a lot of it. Larry achieves that elusive balance between emotion, form and beauty. It’s just wonderful.”

Youtube extract - John White in Berlin