Another Timbre TimHarrisonbre

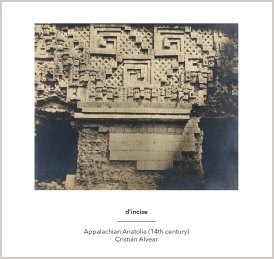

at103 d’incise - ‘Appalachian Anatolia (14th century)’

A 40-minute solo piece for ‘modified guitar’ written by the Swiss

composer d’incise for the Chilean guitarist Cristián Alvear.

Recorded by the composer in Geneva, June 2016

Interview with d’incise

'Appalachian Anatolia (14th century)' is a bizarre title. Could you explain the thinking behind it?

It's a kind of collage-style title that I have used a few times recently, especially

for scored pieces (such as "May my wrongs create no trouble (soft, soft and)" or

"Ukigusa (the sky is as blue as a tragedy)".

I like words, and this title space that

we're given as musicians is a space I fancy playing and experimenting with, a poetic

parallel. But to clarify this particular title (and the others also have clear roots,

in Henry Purcell and Yasujirō Ozu), the "Appalachian Anatolia (14th century)'" score

makes reference to a list of "traditional" music recordings, among which you'd find

banjo, saz and baroque music.

The piece certainly suits Cristian Alvear’s style of playing. Did you compose it with him in mind?

Yes, in fact it was Cristian who first asked me to imagine a piece for him. It was quite a challenge to think about an instrument that I'm absolutely not familiar with. He first gave me some clues about the construction of the instrument, some small details to which I had never paid attention before. Our chat led me finally to the idea of modifying the set-up of the strings, which was also a way for me to simplify the instrument, to bring it down to my electroacoustic level of understanding.

On the one hand I wanted to make a piece with some clear and precise instructions. On the other I wanted to push Cristian a bit outside of what I knew of his usual playing, perhaps something more “on the edge”, or at the confluence of sound, melody, rhythm. Something quiet but somehow driven by a pulse, that was again a confluence between the electroacoustic and the tonal conceptions of music. It turned out that that was what Cristian had been expecting me to do.

But when the piece took shape, it became obvious that it was a work that might also be interesting for other guitarists to confront. That's why I asked Clara de Asis, a young musician living in Marseille, to attempt it on electric guitar. I'm glad because this process revealed very well the balance in the piece between its own fundamental core character, and the interpreter’s touch and input. This a point that is very important for me in such work.

I know that you have a long background in improvised music. When did you start to write compositions, and why do you think that you have moved in this direction?

I guess composition was always present as an inspiration, especially in my electroacoustic work. But it's mostly through the evolution of the Diatribes duo, with Cyril Bondi, that it became a stronger issue (with the piece “Roshambo”, for example). “Ilhas”, for snare drums and loudspeaker, was another milestone. I also began playing scored pieces by other musicians such as Stefan Thut or Magnus Granberg. So, in answer to when I began writing compositions, the answer is a couple of years ago.

Basically I'm trying to find a specific characteristic for each of my projects. I see composing – on paper or verbally – or improvising as tools which allow the revelation of certain forms, colours, or whatever is “unique” to a piece of music. I'm definitely improvising less than I used to, and certainly not in the same way - recently in improvised contexts I've been challenging myself by using a very limited amount of options.

I see composition mainly as an opening to new possibilities. With the search for clarity in what I or we do, came the desire for a better formulation of my or our music. And working on its potential of transmission via a score is a very stimulating mind game.

Anyway “Appalachian Anatolia” is a new step, in that it’s a piece I couldn’t play myself.

In the score of ‘Appalachian Anatolia’ you specify that the interpreter must listen ‘a lot of times’ to certain specific recordings – mainly of various ‘traditional’ folk musics, but also pieces by Guillaume de Machaut and Neil Young – and instruct the interpreter to ‘refer to’ elements from these traditional musics in their interpretation, though not in an obvious way. How do you think Cristian took these references on board in his playing, and was it the kind of use of that material that you were hoping for?

The transposition is not obvious in Cristian's version, which is a good thing, I guess, and I chose not to ask him how exactly he proceeded. When we met we focused more on the overall form of the piece.

This part of the score is a bit paradoxical, and I wanted it that way, counterbalancing the precise tuning and the limitation of material available. I see a tension between this limitation and a theoretical infinity of realisations.

All these musics had a strong impact on me at some point, especially in their traditional aspects - and I would consider the “western/desert movie guitar style” of Neil Young in Jarmush's “Dead Man” as a form of (newer) tradition. I wanted to see how a bridge could be built between these traditional musics which had impressed my younger self, and my own current experimental music. This a field of work which I wish to continue to explore, perhaps making the references more apparent.

There are a few elements you can notice in both Cristian and Clara's approaches, but I think that in both cases the influence of these musics led to a piece with a coherence, a sort of ritual mood, and also a feeling of the vernacular, as if this modified guitar, a new instrument, was also a very old one….which in fact it is.

So will you compose for the guitar again – or indeed for other instruments that you can’t play yourself? Has writing this piece given you the hunger and the confidence to extend the range of your compositional work? What are your plans?

I don't know about the guitar, but for sure I’ll be composing pieces for other instruments. The work with Cristian was very encouraging in this respect and there’s still so much to learn and experiment with. I very much like those forms of dialogue or collaboration between the knowledge and background of an instrumentalist on the one hand, and the conceptual input of a composer on the other. That’s how I see the relation between composer and interpreter, as a horizontal interaction.

I've started to plan a double bass solo, which was requested by Félicie Bazelaire from Paris (in relation with other solo pieces by Bertrand Denzler and Patrica Bosshard). I'm also putting the last touches to a vibraphone piece for two players (I'll be playing on this one - or at least pretending that I can).

Beside all that I'm busy developing a new “proto-techno” project, called Tresque, playing with our traditional-experimental repetitive band La Tène (with Cyril Bondi and Alexis Degrneier), some ideas for more stricly electroacoustic works, and I’m continuing to push the boundaries with Diatribes, my longstanding duo with Cyril Bondi, among many other things.

Cristian Alvear

Cristian Alvear at the recording session for ‘Appalachian Anatolia’

d’incise

Reviews

“At first, Appalachian Anatolia (14th century) seems tentative. Cristián Alvear plucks the same few notes repeatedly, and hinting at but not quite resolving into a melody. The figure shrinks and his playing becomes quieter, as if hesitating. But since Alvear has become a go-to guy in recent years for contemporary composers who need a classical guitarist who can not only play what they request but go beyond the score, the hesitation must be part of the plan.

And then a sonic halo seems to form around his playing. The notes seem to radiate, and the point of what he is doing becomes clear; the sound is the point, not just the notes. A key tool in Alvear’s kit is restraint; he taught himself not to brush the fingerboard between notes in order to secure the necessary stillness for Jürg Frey’s Guitarist, Alone, sustained repetition beyond the point of white knuckles on Sara Hennies’ Orienting Response and gently sculpted the quiet between sounds in order to give shape and presence to Michael Pisaro’s Melody, Silence. For Appalachian Anatolia (14th century), an album-length piece, he focuses on how close to similar notes should be placed together to manage that halo effect while cultivating a contrary tension obtained by having three strings tuned in just intonation and the other three in a more conventional tuning.

But that opening hesitation also honors the piece’s origins. Alvear asked the Swiss musician and composer who calls himself d’incise (always lower case) to compose something for him to play even though he didn’t know a thing about the guitar. So he kept his focus narrow, working from a few pieces of knowledge about how the strings are set up. But even though the composition does not deny d’incise’s unfamiliarity with the guitar, it does make use of his familiarity with a variety of guitar music. The score includes a list of recordings that the performer hears over and over again, and then refers to in non-obvious ways whilst playing the piece. The title acknowledges certain of those recommendations; in addition to North American and Greek folk music, baroque music and Neil Young’s Dead Man soundtrack are on the list.

The composer’s instructions to the player transmit in turn to the listener. Not only do you hear the guitarist’s interpretation of the recommended listening (in addition to Alvear, the piece has been played by French electric guitarist Clara de Asis), the piece itself practically demands to be played again and again, if only to try and crack why a few plucked notes impart so much information. Appalachian Anatolia (14th century) doesn’t sound much like the standard bearers of minimalist music, but it epitomizes successful minimalism’s greatest virtue – making way more than you’d expect from limited means.”

Bill Meyer, Dusted

“Appalachian Anatolia (14th century) is a compelling work of astringent beauty, one that provides an unusual perspective on the old virtuosity vs intuition debate surfacing regularly in experimental music. Hiding subcutaneous complexity beneath seemingly naïve forms, it seems set to satisfy both those who regard high levels of technical expertise as a prerequisite to opening up new possibilities in playing, as well as those others for whom such learning is a straitjacket constraining genuine innovation.

The 40-minute piece was created by the Swiss composer d’incise at the request of its performer, Cristian Alvear, despite the former having never played the guitar – an instrument with which Alvear shows an almost preternatural affinity. Unfamiliarity spurred invention, enabling d’incise to sidestep tradition and instead approach the guitar as a collection of sound sources to exploit rather than an instrument existing at the confluence of several histories of composition and performance. These explorations, and ensuing conversations with Alvear, resulted in score that specifies an alternative tuning – bottom two and top two strings tuned to E, with the middle pair at G, with three of those in just intonation – in addition to note combinations, playing instructions and even suggestions of recordings of traditional music which the performer should ‘reference’.

The product of these deliberation is the strange, off-centre intervals that give Appalachian Anatolia (14th century) its detached, unearthly quality. At times, there’s a seemingly disinterested quality to the arrangements of notes, arbitrary even, which seem designed to lead us away from our conventional modes of listening. In the opening minutes, Alvear’s plucks evoke the plight of the newbie guitar student vainly attempting to get two strings in tune, their semi-tonal chimes steadfastly refusing to merge in unison even as they transform from nagging irritation into balletic mantra. Things gather momentum as the piece progresses, with clusters of picked notes and struck harmonics tumbling from the guitar like tarnished coins tossed into an empty well. But these groupings still seem awkward, lopsided, somehow, the combination of tuning and score leading Alvear away from familiar harmonic patterns and instead playing with the exploratory freedom of a child encountering the guitar for the first time. For the listener, the experience is akin to gazing on the twisting filaments of a Naum Gabo sculpture, its impossible shape seeming to change when viewed from different angles, the delicacy of the interconnected tendrils hiding an underlying tensile strength.

The fact that this freedom is a condition, both of the structure imposed by d’incise’s score and by Alvear’s own incredible level of skill, does not in any way lessen its peculiar power. Both artists have distilled their considerable expertise – the years of study, of reflection, of playing, of composition – into the clear, crystalline forms of Appalachian Anatolia (14th century), transforming it from a piece of composed music into a kind of incantation. Listening becomes an act of devotion, a step into the eternal. Not so much an escape from a hostile world as a meditation, enabling us to face its ravages anew.”

From We Need No Swords blog

“Though it’s true that no two performers will play a piece of music in the same way, the classical music industry’s habit of releasing new recordings of the same handful of pieces over and over again must surely be a sign of either an extremely short memory or of rigor mortis. A search of the venerable classical music retailer Presto’s website reveals 361 recordings of J.S. Bach’s “Goldberg Variations” and 271 of Gustav Mahler’s fifth symphony currently available for purchase (although to be fair some of these appear to be re-boxings of previous recordings). Who has the time to listen to and compare 300+ versions of the same piece? And how many of those recordings shed genuinely new light on the work? Meanwhile, living composers are grateful for even a single recording of their music, despite the fact that it often consciously opens itself to variations in performer choices, ambient environment, or the outcome of chance procedures in ways that previous generations of composers never imagined.

d’incise’s ‘Appalachian Anatolia’ is one recently-composed piece of music that has been recorded twice by different performers, and the differences between the two recordings tell much about its score. The work’s unusual title points to the different influences that the composer wanted to explore, using them as a challenge to the commissioning artist, Chilean guitarist Cristián Alvear. The piece’s rhythmic structure is shaped by the rhythms of Appalachian folk music, while the harmonic structure is loosely based on that of Anatolian music, which makes use of many more intervals between whole tones than Western music does.

Alvear’s recording of the piece demonstrates his trademark precise, even style, and also his willingness to follow d’incise’s lead away from the austere sparseness and simplicity that his recordings of music by the likes of Michael Pisaro, Ryoko Akama, and Radu Malfatti are known for. Notes of slightly different pitches (‘slightly’ to unsubtle Western ears) are played in quick succession, creating a beating that generates movement; as more pitches are added, the music begins to take on a subtle Appalachian twang and shuffle. After series of stark, ringing chords, the repeated notes return at a measured trot, followed by a faint, irregular skittering that closes the recording.

The second recording of ‘Appalachian Anatolia’ comes from Clara de Asís, whose electric guitar immediately lends a sharper, more metallic timbre to the piece compared with Alvear’s acoustic instrument. De Asís’ take on the score demonstrates a different approach to the tuning variations and also to the time relations between the notes, with regularity and precision giving way to fluidity and flexibility. Alvear’s version lays every note out to hear, but de Asís chooses to hide some notes in the decay trails of previous ones, making use of greater variation of dynamics and attack. This creates a more tentative, ambiguous feel, though when the attack is quick the sound can be enticingly brittle and spiky.

Comparing the two versions hints at the great openness and freedom built into d’incise’s score: where Alvear chooses to use ringing plucked chords, for example, de Asís uses quiet, rapid bowing to create a buzzing or humming like a distant swarm of bees. Alvear probably does a better job of bringing out the Appalachian-inspired rhythms intended by the composer, while de Asís’ take has a dynamic, crackling energy and a broader range of timbres. It’s hence not a matter of judging which version of the piece is the ‘best’, or even picking a personal preference, but rather of enjoying and learning from the contrasting possibilities made audible by the two performers. If the classical music industry is mired in self-parody, the independent experimental music scene can sometimes seem obsessed with the new and of short attention span; while 300 versions of ‘Appalachian Anatolia’ would probably be overdoing it, maybe more second and third recordings of existing experimental compositions would be a good and ear-opening thing.”

Nathan Thomas, Fluid Radio

“From the WeNeedNoSwords blog: "The 40-minute piece was created by the Swiss composer d'incise at the request of its performer, Cristián Alvear, despite the former having never played the guitar..."

This is not an unusual approach for a composer; they tend to write for everything, grilling performers about pedal positions, range etc. to create something playable (though often challenging) for a performer. This work, however, is successful in not displaying an intimate knowledge of the guitar that would come from careful conversations with an exclusively Classical performer and/or study of orchestration, tuning, capabilities of the six-stringed instrument.

And that's what makes Appalachian Anatolia (14th Century) so remarkable.

Okay, there was some discussion between the two which lead d'incise (née Laurent Peter) to organize and to "...simplify the instrument, to bring it down to my electroacoustic level of understanding." The result is a capricious exploration of timbre with very few guitarisms involved.

The work begins in a much insulated, claustrophobic tonal circle of placid harmonics. I like to call this type of art "Wind Chime Music"; it's as if a cooling breeze is effortlessly creating a pattern-less sound sculpture — one that you could listen to all day — with very little means. It is delicate, free of time constraints, innocent yet evocative and unconcerned with reaching an end.

Elegantly, the palette expands, as the piece incorporates more harmonic material across the fret board. Near eighteen minutes, the guitarist settles in on a repeated semi-stifled pluck. The listener feels the fingers striking the wood and the ghostly, shimmering tremolo hovering with each knock and microtonal relationship of close intervals. The minimalism here makes you lean in more as each isolated sonic element grabs your attention.

After pausing, the mute comes off for the remaining six minutes, strings buzzing as a hammered dulcimer. The visual image the music invokes is roots spreading across soil, or cellular fission, or crickets chirping in a field — or maybe my brain is plagued with this type of microscopic, time-elapsed visage from watching Microcosmos too many times. And as care-free as it began, so ends Appalachian Anatolia (14th Century) in a gentle waft across the horizon.”

Dave Madden, Squid’s Ear